On the morning of February 18th, six students and myself boarded the bullet train that would take us on a 5-day study trip to Minamiuonuma, a city in the Niigata Prefecture of Japan. Though famous for the gargantuan amounts of snowfall recorded every year, we had been told that this year, remarkably enough, there was no snow in the city. Many of us who had been looking forward to playing in the snow, skiing, and all manner of snow activities, were disappointed. Winter and snow holds a particularly special place in my heart, having been raised in the harsh winter regions of the United States, and I was looking forward to experiencing what I considered the first real “winter” since coming to Tokyo.

Not knowing what to expect, we settled ourselves into our seats on the train, watching dejectedly out the window as the bare fields and hills flashed past. We enter a long tunnel, the last mountain range we have to cross before we arrive at our destination. We’re left in darkness for quite a while, five minutes at least, before we emerge — into a beautiful world covered in white. The students, who’d been on their phones or talking quietly amongst themselves, surge up as one to crowd around the windows to plaster their faces on the cool surface as if to feel the falling snow on their cheeks. It was like entering one world from the next. From what the locals told us, snow had begun falling the evening before and kept snowing the whole day and night we arrived as if to welcome us to Niigata.

Not knowing what to expect, we settled ourselves into our seats on the train, watching dejectedly out the window as the bare fields and hills flashed past. We enter a long tunnel, the last mountain range we have to cross before we arrive at our destination. We’re left in darkness for quite a while, five minutes at least, before we emerge — into a beautiful world covered in white. The students, who’d been on their phones or talking quietly amongst themselves, surge up as one to crowd around the windows to plaster their faces on the cool surface as if to feel the falling snow on their cheeks. It was like entering one world from the next. From what the locals told us, snow had begun falling the evening before and kept snowing the whole day and night we arrived as if to welcome us to Niigata.

Throughout our five days there, we had many amazing and unique experiences. Despite hearing about Japan’s super-aged population, in Tokyo it is a distant problem that many of us are aware of but don’t truly comprehend. Seeing tiny villages in the mountains of Niigata comprised of only 50 or so elderly people who have to rise at the crack of dawn to shovel 3-4 meters of snow from their roofs and roads, only for their back-breaking work to be buried by midday. How the local elementary school has less than 20 students total where teachers are forced to combine grade levels and teach integrated courses because of how few children there are. Visiting the Echigo Jōfu weavers whose population has dwindled so much that it is a dying craft that very few still know how to do. All of these things amounted to the stark realization that Japan’s shrinking population is a very real issue that is pushing the cultural richness and tradition of the rural regions to extinction.

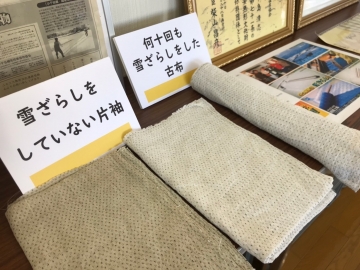

Furthermore, for those of us that came from Tokyo, the 1-2 meters of snow that we encountered in our time there were massive. Yet for the local populace who are used to upwards of 5 meters, so much of their livelihood depends upon the snow and this year was a devastating blow. There were so many ways in which snow plays an unseen but vital role in their way of life, from watering their rice paddies, to oxidizing and cleansing their Echigo Jōfu fabrics, to keeping the wild animals from descending into the valley and disturbing their city; these things made us realize that unlike the metropolis of Tokyo, wherein our lives have become completely disconnected from nature and no matter the weather or the rising and setting of the sun, we operate entirely upon numbers, machines and technology. So different from the people who awake with the sun, who use the snow and the nature that has been gifted them to live alongside and in harmony with their environment, as a part of nature rather than as its masters, as we sometimes purport ourselves to be.

More than anything, this trip taught me the importance of the natural world and no matter where you live, to sometimes take a step back to reevaluate our place in things, and to not forget the significance of the role it plays. We are just as much a part of nature as it is a part of us. To forget that is like a tree forgetting it was born from an acorn. Whether we live in Tokyo, Berlin, New York, or a tiny mountainous village in Niigata, we should remember our roots and strive to live as one with nature. So maybe consider switching off your phones, closing your laptops, taking off your watches, and just stop and smell the roses and give thanks for what we have been given.

(School of International Liberal Studies, K.M.)