Waseda Frontline Research Vol. 11 – 5: Dialogue in a Global Context – The Future of International Japanese Studies (Part 5 of 6)

Thu, Oct 27, 2016-

Tags

Professor Hirokazu Toeda, scholar of modern Japanese literature

School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Part 5: Translating Japanese literature – Reading Haruki Murakami

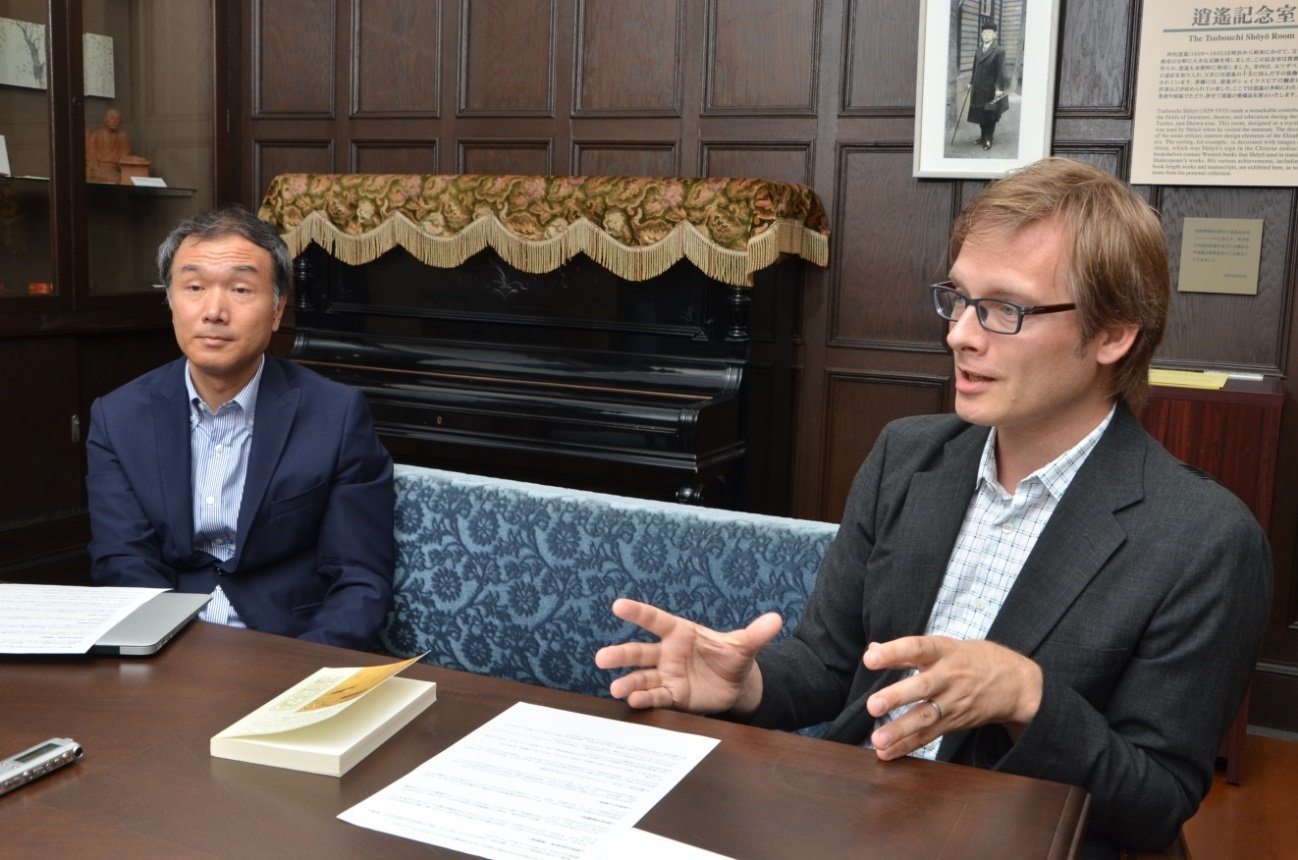

In Part 5 of this series, Hirokazu Toeda, professor at the School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, spoke with Michael Emmerich, associate professor at UCLA’s Department of Asian Languages & Cultures. Professor Toeda, a specialist in modern Japanese literature, was invited to lecture at Columbia University ten years ago, where he built a stronger network with scholars of Japanese literature overseas. He became particularly close to Professor Emmerich, who appears in this section. Professor Emmerich has translated a wide range of Japanese literature into English, from works by modern and contemporary authors such as Yasunari Kawabata and Banana Yoshimoto to classical texts such as the Noh play “Kagekiyo.” Their conversation on Japanese literature from a global perspective and university education is presented here in two parts.

In Part 5 of this series, Hirokazu Toeda, professor at the School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, spoke with Michael Emmerich, associate professor at UCLA’s Department of Asian Languages & Cultures. Professor Toeda, a specialist in modern Japanese literature, was invited to lecture at Columbia University ten years ago, where he built a stronger network with scholars of Japanese literature overseas. He became particularly close to Professor Emmerich, who appears in this section. Professor Emmerich has translated a wide range of Japanese literature into English, from works by modern and contemporary authors such as Yasunari Kawabata and Banana Yoshimoto to classical texts such as the Noh play “Kagekiyo.” Their conversation on Japanese literature from a global perspective and university education is presented here in two parts.

(Date: July 14, 2015)

Emmerich: Initially proposed by Professor Toeda, he and I organized an international symposium together in Los Angeles in May 2015 called Tokyo Textscapes. The word “textscapes” is a word my colleague Seiji Lippit coined. The purpose of this symposium was, briefly put, to reexamine modern Japanese literature by approaching texts depicting Tokyo, a popular stage of modern literature, from various angles.

Toeda: Yes, and I felt it would be interesting to do that in Los Angeles, far away from Tokyo.

Emmerich: Talking about Tokyo in Tokyo has different implications than doing so when in Los Angeles. That’s the strong impression I got from the symposium. Also, there were many Japanese guest speakers, the majority of whom said it was the first time they had given a presentation about Tokyo abroad. The event seemed to offer a new experience for everyone.

Photo: “Tokyo Textscapes” international symposium poster

The symposium was jointly held by UCLA and Waseda University on May 8-9, 2015. By approaching texts depicting Tokyo in different ways, the aim was to reexamine Japanese modern literature through comparison and analysis of the relationship between contemporary and pre-modern times as well as different regions around the world. The poster was designed by Professor Emmerich.

Toeda: In the presentations, we heard many reports on the relationship between literature and the transformation of Tokyo during its rapid economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s. All presentations were incredibly fascinating. There were an equal number of native Japanese and English speakers in the audience. On this point as well, we managed to hold a symposium on Tokyo-based literary works in a global context.

We are focused on creating opportunities to reflect on Japanese literature from an international perspective and sharing information among Japanese literary scholars who differ widely according to their country, language, and particular era and genre of study.

Emmerich Speaking of understanding Japanese literature from a global perspective, the author Haruki Murakami may be a good example. Murakami’s novels are read all over the world, of course in translated form, which holds great significance.

I once had an opportunity to hear Murakami’s Indonesian translator speak. Evidently all the sex scenes had to be been removed in Indonesian editions, even in Norwegian Wood. This means the creation of a Norwegian Wood without any sex scenes, so in actuality, whom can we say this work belongs to? Translations always throw these kinds of questions at us.

Toeda: When Professor Emmerich lectured at Waseda University last year, he referred to the differences between the reception of Haruki Murakami in Japanese and in English. I think this is an extremely significant point he raised.

For instance, the translations of Murakami’s works were published in a different order than the original Japanese books, so English readers read them in a completely different sequence. Furthermore, because some works have not been translated, non-Japanese readers may have a different impression of Haruki Murakami as a writer. It is also possible that his works are even appreciated on different levels in certain linguistic areas because they have been partially edited, such as the Indonesian edition I mentioned above. Therefore, although Haruki Murakami’s works have been translated and read in various languages, the impressions they make on their respective readers may differ greatly.

Some say that Haruki Murakami is accommodating for the era of globalization because of the setting of his stories and stateless nature of his characters, but rather than studying and evaluating how he is received around the world, it may be more valuable going forward in understanding the differences between translations.

Emmerich Haruki Murakami’s case is especially interesting because his books have undergone translations into English by several translators, and each translator has translated them in different ways. Take Norwegian Wood, for example, of which translations by Alfred Birnbaum (an American translator of Japanese literature and media artist) and Jay Rubin (an American translator of Japanese literature, researcher, and professor emeritus at Harvard University) are available. These two English versions have some major differences in their fundamental perception.

At the very beginning of the book, for instance, when the protagonist arrives in Germany, Birnbaum writes “Here I am, thirty-seven years old,” whereas Rubin writes “I was thirty seven then …” as though looking back at the past. This is the very first problem that arises when translating from Japanese, which can be said to have no tenses, into English, which does have tenses. Translators ponder how they are going to translate this text from this point onward.

The distinction between translators themselves also shows in their slightly different word choices. Rubin is a professor emeritus at Harvard University while Birnbaum is a freelance translator. The difference between the two translations in terms of the storyteller’s position, writing style, and choice of words is also related to the two translators’ differing attitude towards the work.

Thus, the impression of a work varies greatly depending on the existence of its translator. That is, the Japanese and English versions of Haruki Murakami do not simply differ in terms of language style but, in some cases, offer a completely alternative reading experience.

Viewed in this light, it seems strange to even ask why Haruki Murakami is globally popular or what the essence of his writing is in the first place. The international popularity of a particular book can’t necessarily be thought of in terms of the global “reception” of a single, unchanging text. Instead, we could say that it has spread as it underwent various transformations through translations.

Toeda: I completely agree. Haruki Murakami’s novels, which have spread worldwide, exemplify inevitable transformations made by the hands of various individuals. In contrast, we could study the Shinkankaku-ha (New Sensationalist school) movement in Japanese modern literature, which incorporated social changes as well as new art and culture flowing in from around the world.

Photo: (From left) Shinzaburo Iketani, Riichi Yokomitsu, Teppei Kataoka, Yasunari Kawabata and Kan Kikuchi at the Fukushima lecture of a Tohoku lecture tour sponsored by Bungeishunju Publishing Company in June 1927

(Source: Museum of Modern Japanese Literature, collection number: P0001016)

Photo: A Page of Madness (Source: National Film Center)

Japan in the 1920s saw a huge increase in technologies from Europe such as radio, publication culture and film. Members of the so-called Shinkankaku-ha literary group, which included Riichi Yokomitsu and Yasunari Kawabata, formed the Shinkankaku-ha Eiga Domei (New Sensationalist School Film Alliance) together with other literary figures and young film directors. They produced the 1926 film “A Page of Madness,” an experimental work that attempted to convey a story through moving images alone, without a narrator or subtitles.

They devoutly dedicated themselves to new forms of cinematic expressions and utilized this experience in literary expressions of their own novels. For instance, Riichi Yokomitsu’s masterpiece “Machine” (1931) precisely verbalized a stream of consciousness modeled on the continuity of film. The novel contains the term “moving picture,” and it has an overall feel of a movie.

In the final part of this series, the two professors, both of whom play a significant role in Japan and America in the field of modern Japanese literature, will talk about university education in the two countries.

☞Part 1

☞Part 2

☞Part 3

☞Part 4

☞Part 6

Profiles

Michael Emmerich

Michael Emmerich

Michael Emmerich was born in New York in 1975. After earning a PhD in East Asian Languages and Cultures from Columbia University, he spent two years as a postdoc at Princeton University’s Society of Fellows and then taught as assistant professor at University of California, Santa Barbara before taking his position as associate professor at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)’s Department of Asian Languages & Cultures in 2013. He is a scholar of Japanese literature who has conducted a wide range of research, varying from “The Tale of Genji” to modern literature, and is also an active translator of works by modern and contemporary authors such as Yasushi Inoue, Genichiro Takahashi, and Banana Yoshimoto. He won the 2010 Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature for his translation of Hiromi Kawakami’s “Manazuru.” In 2013, he was shortlisted for the Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Awards for his translation of Hideo Furukawa’s “Belka, Why Don’t You Bark?” He was the judge for the 25th Waseda Bungaku Prize for New Writers. He also directs the Tadashi Yanai Initiative for Globalizing Japan Humanities (a project created by a donation from Waseda alumni Tadashi Yanai, founder and president of Fast Retailing), and took the lead creating “The Hentaigana App,” which was co-released by Waseda and UCLA in autumn 2015.

Professor Hirokazu Toeda

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Professor Hirokazu Toeda graduated from Waseda University’s then School of Letters, Arts and Sciences before going on to study Japanese literature the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, where he obtained his PhD in literature. He served as an assistant professor at Otsuma Women’s University before returning to Waseda University as an associate professor. He has served as a professor since 2003. He also frequently takes on collaborative posts overseas, such as visiting professor at UCLA in 2015 and visiting researcher at Columbia University in 2015 and 2016. Professor Toeda received the Utsubo Kubota Prize for Literature in 1994. His field of specialization is modern Japanese literature (literary modernism centered on the New Sensationalist school of Japanese writers, modern Japanese literature and the media and the interrelation between literature and censorship during the Allied occupation, etc.) His publications include “Shigeo Iwanami—Living Low, Thinking High” (Minerva Shobo, 2013), “Masterpieces Can Be Made—Yasunari Kawabata and His Works” (NHK Publishing Inc., 2009), “Censorship, Media and Literary Culture in Japan: from Edo to Postwar” (co-author and co-editor, Shinyosha, 2012), “Survey of Magazines during Occupation—Literary Edition, Volumes 1-5” (co-author/editor, Iwanami Shoten, 2009-2010), “The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature” (co-author, Cambridge University Press, 2015), and a commentary on Parts 1 and 2 of Riichi Yokomitsu’s “Ryoshu” (Iwanami Shoten, 2016).

Venue

Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum (commonly known as “Enpaku”)

Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum was established in October 1928. At its opening ceremony, Shoyo Tsubouchi is quoted as having said: “To create good theatre, you need to build its foundation by gathering, arranging, and making comparative studies of theatre-related materials from Japan and overseas, past and present.” The museum inherits this aspiration to this day and has collected, stored, and exhibited precious materials from all ages and cultures. Including more than a million artifacts, the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum is one of the foremost theatre museums in the world and the only one in Asia, which is cherished and supported by theatre actors, enthusiasts and scholars alike.