Waseda Frontline Research Vol. 11 – 6: Dialogue in a Global Context – The Future of International Japanese Studies (Part 6 of 6)

Thu, Oct 27, 2016-

Tags

Professor Hirokazu Toeda, scholar in modern Japanese literature

School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Part 6: Japanese literature in world culture

In part 6, the final part of this series, Professor Hirokazu Toeda of the School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and Michael Emmerich, associate professor at UCLA’s Department of Asian Languages & Cultures, continued their dialogue. This time, they discussed their vision of education, with a focus on Japanese literature, and the differences between university education in Japan and the U.S.

(Date: July 14, 2015)

There are significant differences in education methodologies between the Japanese and American universities where you both teach. In the U.S., the emphasis is on liberal arts education whereas in Japan, there is a tendency to require a high level of specialization at an earlier stage of higher education. How does this affect the mindset and roles of researchers in the two countries? Please give us your thoughts.

Toeda: I suppose the different ways in which education is conducted mean differences between the roles of researchers. For instance, Professor Emmerich studied at Princeton University but didn’t specialize in Japanese literature at the undergraduate level. He received a liberal arts education before specializing in Japanese language and Japanese literature at graduate school. Then, as his graduation project, he translated Yasunari Kawabata’s novel Fuji no Hatsu Yuki and published it under the title First Snow on Fuji. This is wonderful, and we see from Professor Emmerich’s case that it is possible to master a specialized field of research while studying liberal arts. In addition, it is because of his liberal arts studies that he had such broad interests and gained such comprehensive scholarly knowledge.

Emmerich: I think that my studying a broad range of fields is to some extent related to the fact that the United States does not have so many scholars of Japanese literature. At UCLA, for instance, there are approximately 900 students of English and American literature but only about 80 majoring in Japanese studies and studying Japanese language and literature. In the same way, at all universities throughout America, there are only a few teachers specializing in Japanese literature and, in some cases, there may only be one. As a result, we may have no choice but to broaden our field and, for example, be asked to teach not only Japanese but also East Asian literature.

Toeda: When I had the opportunity to lecture at UCLA, I was surprised by how the students immediately expressed their opinions or asked questions after I had spoken, which was a very different response in comparison to my students in Japan. When I think about why this is, perhaps it is because of the different way they view knowledge. While Japanese students are “accumulators,” who attach importance to the accumulation of knowledge, their American counterparts are “operators,” who focus on how to utilize the knowledge they have just obtained in order to gain further knowledge.

Even when Japanese students have acquired some knowledge, they think they need to understand more in-depth before speaking up. Americans, on the other hand, try to use a new piece of knowledge in order to increase it tenfold. I think this may be the reason why they were so quick to give their opinions and thoughts in response to what I said during my lessons.

In Japan, the common way to become an author is by writing a book independently and winning a literary prize. While in America, we hear of more writers who studied creative writing at university.

Toeda: Waseda University has an established reputation in creative writing. A former winner of the Akutagawa Prize, Author and Professor Toshiyuki Horie (Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences) teaches hands-on creative writing in his own seminars. One of his former students is Ryo Asai, the winner of the Naoki Prize in 2013. So in these terms, we can say that Waseda University does have a creative writing course that trains authors. However, there are not many places in Japan that offer such opportunities.

Emmerich: Not all students of creative writing courses necessarily become writers themselves, but a common path is to obtain an MFA (Master of Fine Arts) degree before becoming a novelist. There are some who follow the more Japanese-type route of writing on their own and winning a literary prize out of the blue, but this is fairly uncommon. Consequently, we are starting to grasp the procedures of becoming an author and even the method of writing creatively, which follow a set of patterns. That is to say, to some extent a shared understanding may exist on where to learn, what kind of thing to write, and where to get published.

In the Japanese literary world, on the other hand, because there is no American-style of “shared understanding,” so a totally unexpected, attractive work suddenly appears in literary journals from time to time.

In this way, Japan and America have completely different forms of literature. We cannot say which is better. Personally, I think it is amazing how Japanese literary journals have built a platform to introduce extremely rare authors such as Masaya Nakahara.

Toeda: In America, students acquire a certain level of practical training that will enable them to work to some extent beforehand by simply studying at university, as observed in the way where creative writing classes properly function as a course at universities in addition to other studies. In Japan, on the other hand, people assume they will be trained in the workplace, no matter what their specialization is. This may even be the same for writers. It is said that Japanese authors are guided by editors. However, this may eventually be handled at the university level even in Japan.

American universities seem to maintain a very good balance between practical learning and things like liberal arts.

Emmerich: I wouldn’t call it a balance. A balance would mean weighing the study of practical sciences and humanities as a separate discipline, which isn’t the case.

For example, the sensibility of Steve Jobs of Apple Inc. lay firmly within the humanities, not the sciences. He had a desire to create beautiful things, which people working under him at Apple achieved by using scientific knowledge. The core of this was not technology but his personal aesthetic sense.

Perhaps all successful businessmen, regardless of their field, have that kind of humanities-based sensibility. The humanities develop our ability to grasp the essence of things. It is the humanities that nurture people’s ability to perceive the meaning behind the words they read in an email, a newspaper or elsewhere, or their intuition to detect the true intentions of a customer they are talking to at work.

The sciences and the humanities are not distinct but rather intertwined. I think it’s important to be aware of this relationship and study them both simultaneously.

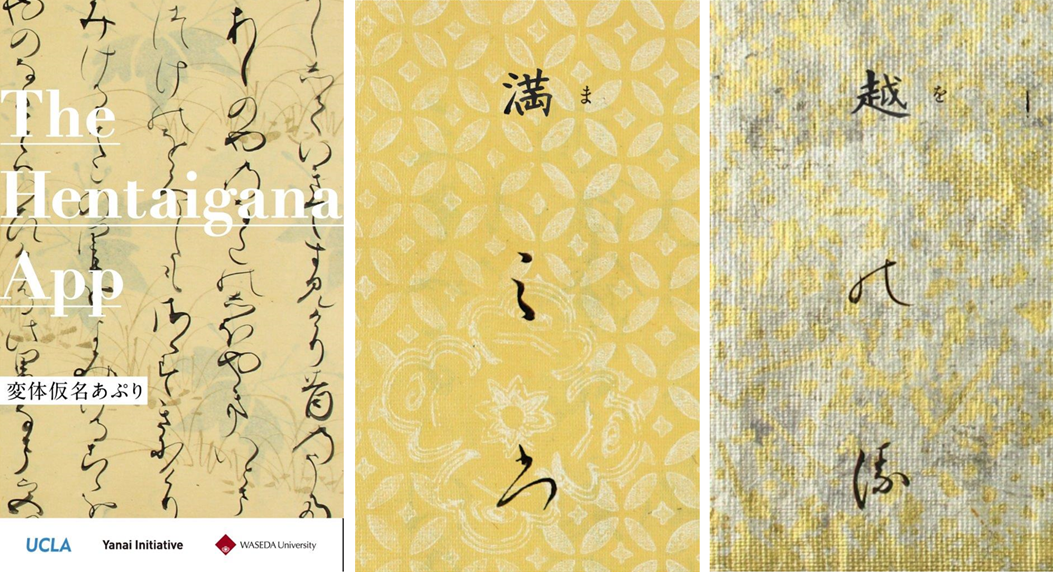

Photo: “The Hentaigana App” a free smartphone app which combines the sciences and the humanities. Proposed by Professor Emmerich and jointly developed by Waseda University and UCLA with the participation of Japanese literature scholars, such as Professor Toeda, and programmers abroad. The Android version was released on October 29 and the iOS version on November 4, 2015

That’s exactly what a liberal arts education at an American university stands for. Waseda University wants to nurture many talented scholars. In closing, could you therefore give a message to those who are aiming to become researchers in future?

Emmerich: Excellent scholars at Waseda are making a difference overseas. Professor Toeda is among them, and he is traveling internationally to New York and Paris and attesting that Japanese literature is no longer an exclusive domain of Japan. Also, no other Japanese university is as engaged as Waseda in making different approaches and collaborating closely with universities aboard such as Columbia University and UCLA. I genuinely hope many of you will make an entrance onto the world stage by choosing to study in such stimulating environment.

Toeda: I have been committed in conducting educational research, including my frequent visits overseas for the past ten years, in which I have had opportunities to meet Professor Emmerich and other inspirational scholars from around the world. For Japanese students who intend to study Japanese literature, it will be important to have consciousness of working with scholars worldwide, not only in Japan. Japanese literature no longer belongs to Japan alone and has become part of the world’s culture.

I think the advantage of studying at Waseda University is that it brings world-class research into view, enabling students to meet frontline researchers and experience firsthand what these researchers have to offer. I am excited by the prospects of seeing even more future scholars who are motivated to pursue their research in Japanese literature at Waseda.

☞Part 1

☞Part 2

☞Part 3

☞Part 4

☞Part 5

Profiles

Michael Emmerich

Michael Emmerich

Michael Emmerich was born in New York in 1975. After earning a PhD in East Asian Languages and Cultures from Columbia University, he spent two years as a postdoc at Princeton University’s Society of Fellows and then taught as assistant professor at University of California, Santa Barbara before taking his position as associate professor at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)’s Department of Asian Languages & Cultures in 2013. He is a scholar of Japanese literature who has conducted a wide range of research, varying from “The Tale of Genji” to modern literature, and is also an active translator of works by modern and contemporary authors such as Yasushi Inoue, Genichiro Takahashi, and Banana Yoshimoto. He won the 2010 Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature for his translation of Hiromi Kawakami’s “Manazuru.” In 2013, he was shortlisted for the Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Awards for his translation of Hideo Furukawa’s “Belka, Why Don’t You Bark?” He was the judge for the 25th Waseda Bungaku Prize for New Writers. He also directs the Tadashi Yanai Initiative for Globalizing Japan Humanities (a project created by a donation from Waseda alumni Tadashi Yanai, founder and president of Fast Retailing), and took the lead creating “The Hentaigana App,” which was co-released by Waseda and UCLA in autumn 2015.

Professor Hirokazu Toeda

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Professor Hirokazu Toeda graduated from Waseda University’s then School of Letters, Arts and Sciences before going on to study Japanese literature the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, where he obtained his PhD in literature. He served as an assistant professor at Otsuma Women’s University before returning to Waseda University as an associate professor. He has served as a professor since 2003. He also frequently takes on collaborative posts overseas, such as visiting professor at UCLA in 2015 and visiting researcher at Columbia University in 2015 and 2016. Professor Toeda received the Utsubo Kubota Prize for Literature in 1994. His field of specialization is modern Japanese literature (literary modernism centered on the New Sensationalist school of Japanese writers, modern Japanese literature and the media and the interrelation between literature and censorship during the Allied occupation, etc.) His publications include “Shigeo Iwanami—Living Low, Thinking High” (Minerva Shobo, 2013), “Masterpieces Can Be Made—Yasunari Kawabata and His Works” (NHK Publishing Inc., 2009), “Censorship, Media and Literary Culture in Japan: from Edo to Postwar” (co-author and co-editor, Shinyosha, 2012), “Survey of Magazines during Occupation—Literary Edition, Volumes 1-5” (co-author/editor, Iwanami Shoten, 2009-2010), “The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature” (co-author, Cambridge University Press, 2015), and a commentary on Parts 1 and 2 of Riichi Yokomitsu’s “Ryoshu” (Iwanami Shoten, 2016).

Venue

Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum (commonly known as “Enpaku”)

Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum was established in October 1928. At its opening ceremony, Shoyo Tsubouchi is quoted as having said: “To create good theatre, you need to build its foundation by gathering, arranging, and making comparative studies of theatre-related materials from Japan and overseas, past and present.” The museum inherits this aspiration to this day and has collected, stored, and exhibited precious materials from all ages and cultures. Including more than a million artifacts, the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum is one of the foremost theatre museums in the world and the only one in Asia, which is cherished and supported by theatre actors, enthusiasts and scholars alike.