Waseda Frontline Research Vol. 11 – 2: The City within a City – Ginza in Japanese Literature: a Dialogue between Prof. Toeda and Prof. Campbell Parts 2-4

Fri, Sep 16, 2016-

Tags

Professor Hirokazu Toeda, scholar of modern Japanese literature

School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Part 2: The Soundscape of Ginza – The Wakō Bell

In Part 2, Professor Hirokazu Toeda at the School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Professor Robert Campbell at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences continue their dialogue, this time talking about the soundscape found within literary works set in Ginza, such as the Wakō bell.

(Date: April 25, 2016)

Campbell: In Tokyo/Gingai Shōshi [Tokyo/Ginza town magazine] (1882), mentioned in Part 1, Ginza covered “approximately hatchō (8-chō),” equivalent of about 870 meters today. This suggests a common topographical perception of Ginza. For instance, it was included in the title of Rintarō Takeda’s novel “Ginza Hatchō” (1935). Another characteristic of novels set in Ginza is that they often portray the passage of time or the changes in atmosphere over time. The ringing bell at Hattori Tokeiten store (now Wakō), a symbol which also frequently appears in novels, tells people the time. We could say that this bell’s sound is an essential component of Ginza’s soundscape.

Tomoichirō Inoue, for example, published about ten novels set in Ginza during the occupation of Japan immediately after World War II. One of them, “Gozen Reiji [Midnight]” (1953), which was serialized in the Yomiuri Shimbun evening paper from 1952, contains the following passage:

Ding…

Dong…

Ding…

The clock tower eventually starts resonating its eloquent sounds, telling time.

How many times will it ring?

Eiko Uchiumi unintentionally counts the bells as she stands under the eaves of a dim-lit beer hall on the intersection of Owari-Chō. However, she definitely knows for sure that the bell will ring twelve times. Because Eiko left the Kyōwa Hall in Tsukiji at exactly 11:40PM, it has to be 12 o’clock that the Hattori Clock Tower is pealing now.

“Gosh… I have to wait in a place like this, again…”

Although they had phoned each other and Tatsuya Tamaki asked Eiko to meet him in this beer hall on the corner of Owari-Chō, he has not arrived yet. Waiting and having to wait are ordinary courses of love, but even so, there is no etiquette or good excuse for flaking out at this hour in the rainy Owari-Chō.

Ding…

Dong…

Ding…

The clock is taking its precious time to strike the remaining hours as the bell’s sound echoes in the distance graciously. Come to think about it, this clock’s bell ridiculously takes forever reaching 12 o’clock.

(From “Kousaten [Intersection],” the first chapter of “Gozenreiji [Midnight]”)

This shows that the distance from Kyōwa Kaikan in Tsukiji to Owari-chō intersection (now Ginza Yon-chōme crossing) took less than 20 minutes on foot. Also, time is expressed by the Hattori Tokeiten’s bell, not the reading of its dial. This is a scene in which sound and space are illustrated as one.

Photos: Hattori Tokeiten upon completion (left) and Wakō store now (right) (Images: Wakō)

Toeda: That’s fascinating. Are there any other soundscapes of Ginza?

Campbell: There are many descriptions of sounds of transportation, such as horse-drawn trams, rickshaws, and car horns. Also, the opening scene of Shūsei Tokuda’s novel “Shukuzu [Reduced Drawing]” (first published in the Miyako Shinbun, 1941) has two characters sitting on the second floor of Shiseido (now Shiseido Parlour) and chatting while watching the traffic on Ginza Street below. They describe the crowds of people and the stream of vehicles below separated from them by a single sheet of glass.

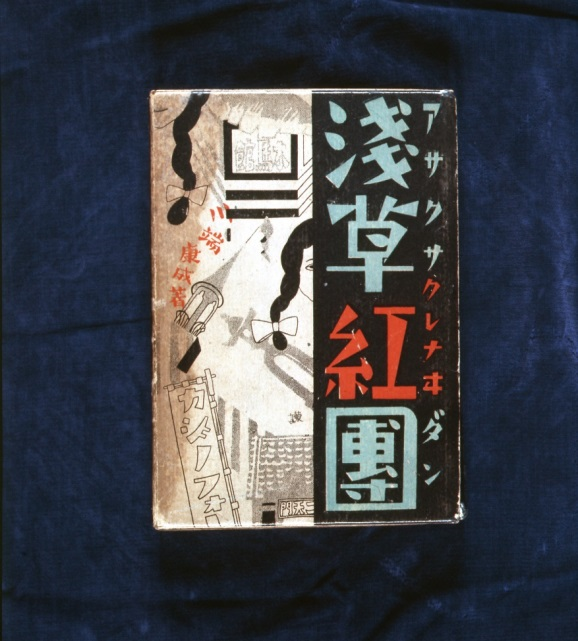

Toeda: The characteristics of a city emerge from its sound, don’t they? Yasunari Kawabata also selects a variety of very different sounds to depict the grandeur of the post-quake reconstruction of Asakusa in “Asakusa Kurenaidan [The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa]” (1930). To represent the bustle and dynamism of the streets being restored, he lists sound after sound, such as clips of newly started radio broadcast, footsteps of people visiting the temple, chimes of the temple’s bells, and the clinking of coin offerings.

(From Chapter 32 in “Asakusa Kurenaidan [The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa]”)

Kawabata, Yasunari. “Asakusa Kurenaidan [The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa].” Senseisha, 1930. Box Design by Kenkichi Yoshida. (Source: The Museum of Modern Japanese Literature, collection number: P0001016)

(From “Ginza no Asa [The Mornings of Ginza]”)

There are few direct descriptions of sounds within this book. However, the calls of merchants and the sounds of traveling musicians playing gekkin (Chinese lutes) and singing hōkai-bushi songs, set against traffic sounds such as the loud clanking of horse-drawn trams starting up and the noise of rickshaw wheels on the ground, implies the street’s vibrancy. This highlights the surreptitious manner of the female worker who enters the story at that point. Okamoto is not a proletarian literature writer, but he has picked out this particular figure of the worker, portraying a person who seems overwhelmed in the underbelly of the prosperous town.

Photo: Professor Campbell provided extracts from a number of literary works

Toeda: Talking about horse-drawn trams, this reminds me of a scene from Natsume Sōseki’s “Sanshirō” (1909) in which the protagonist, Sanshirō Ogawa, arrives in Tokyo and is surprised at first by the jingling bells of the trains at Marunouchi, near Ginza. What surprises Sanshiro most is that “No matter how far I go, Tokyo never ends.”

Talking about horse-drawn trams, this reminds me of a scene from Natsume Sōseki’s “Sanshirō” (1909) in which the protagonist, Sanshirō Ogawa, arrives in Tokyo and is surprised at first by the jingling bells of the trains at Marunouchi, near Ginza. What surprises Sanshiro most is that “No matter how far I go, Tokyo never ends.”

Morioka Shoten’s location, where this dialogue is taking place, was previously called Kobiki-chō and used to be an artisan district long ago. I have heard from people born and raised here that Kobiki-chō was a town rich in sounds, where one could hear craftsmen making all kinds of things. It was an atmosphere of songs and dance with the nearby Kabuki-za Theater. When we think about present-day Ginza, it seems to revolve around modern sounds, but we know that in days gone by, it was colored by a variety of sounds that conjured up people’s occupations.

In the years since Kido Okamoto’s “Ginza no Asa,” which you mentioned earlier, writers and poets influenced by futurism (futurismo in Italian), a concept originating from Italy and introduced into Japan in the early 20th century, depicted Ginza as it underwent modernization. In the eyes of the creative minds drawn to the avant-garde art movement, which renounced traditional art and glorified the mechanical beauty, speed and dynamism of the new era, Ginza must have appeared to be a very attractive town. Hence, what they chose were the modern sounds emitted by cars, elevators and so on. Regarding the transformation of the Tokyo sounds, including Ginza, reading the diary of Kafu Nagai, “Danchōtei Nichijō [The Danchōtei Diary]” (1917-1959), provides a taste of the sounds that he heard during the Taishō era and well into the Shōwa era.

I believe there could be new discoveries if we collected the ways in which different writers expressed sounds and considered the transformation of space and time when depicting Tokyo.

In the next session, the two professors will discuss Ginza and literature during the occupation.

Profiles

Professor Robert Campbell

Professor Robert Campbell

Born in New York, Professor Robert Campbell graduated from University of California, Berkeley and earned a PhD in literature from the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University. He moved to Japan in 1985 as a research student in the Faculty of Humanities, Kyushu University, later joining the faculty as an assistant professor. He also served as associate professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature and associate professor and later professor at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo. His specialization is Japanese literature from the Edo to Meiji period. His publications include “Robert Campbell no Shosetsuka Shinzui—Gendai Sakka Rokunin to no Taiwa [Dialogue With Six Contemporary Artists – Novelist Essence of Robert Campbell]” (NHK Publishing, 2012), “J-Bungaku—Eigo de Deai, Nihongo wo Ajiwau Meisaku 50 [J-Literature: Fifty Masterpieces to Encounter in English and Relish in Japanese]” (University of Tokyo Press, 2010), “Kanbun Shosetsu Shu [Meiji Novels Written in Classical Chinese]” (Iwanami Shoten, 2005), “Yomu Koto no Chikara―Todai Komaba Renzoku Kōgi [The Power of Reading―Lectures at Komaba, the University of Tokyo]” (Kodansha, 2004) and “Kaigai Kenbun Shu [A Collection of Observations from Abroad]” (co-writer, Iwanami Shoten, 2009). He is also active in the Japanese media where he utilizes his expertise in literature as a television host, news commentator, newspaper columnist, book reviewer and radio personality.

Professor Hirokazu Toeda

Professor Hirokazu Toeda

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Professor Hirokazu Toeda graduated from Waseda University’s then School of Letters, Arts and Sciences before going on to study Japanese literature the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, where he obtained his PhD in literature. He served as an assistant professor at Otsuma Women’s University before returning to Waseda University as an associate professor. He has served as a professor since 2003. He also frequently takes on collaborative posts overseas, such as visiting professor at UCLA in 2015 and visiting researcher at Columbia University in 2015 and 2016. Professor Toeda received the Utsubo Kubota Prize for Literature in 1994. His field of specialization is modern Japanese literature (literary modernism centered on the New Sensationalist school of Japanese writers, modern Japanese literature and the media and the interrelation between literature and censorship during the Allied occupation, etc.) His publications include “Shigeo Iwanami—Living Low, Thinking High” (Minerva Shobo, 2013), “Masterpieces Can Be Made—Yasunari Kawabata and His Works” (NHK Publishing Inc., 2009), “Censorship, Media and Literary Culture in Japan: from Edo to Postwar” (co-author and co-editor, Shinyosha, 2012), “Survey of Magazines during Occupation—Literary Edition, Volumes 1-5” (co-author/editor, Iwanami Shoten, 2009-2010), “The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature” (co-author, Cambridge University Press, 2015), and a commentary on Parts 1 and 2 of Riichi Yokomitsu’s “Ryoshu” (Iwanami Shoten, 2016).

The venue

Morioka Shoten, Ginza Branch

The dialogue took place at Morioka Shoten, Ginza Branch, located on the first floor of Suzuki Building in Ginza-Itchōme. Under the concept of “selling one book at a time,” this store adapts the unique business style of selling only one kind of book per week and creating elaborate displays, which attract many visitors from abroad as well.

Photos, Left: Morioka Shoten Ginza Branch in Ginza-Itchōme Right: (From left) Prof. Robert Campbell, Prof. Hirokazu Toeda, and Morioka Shoten Manager Yoshiyuki Morioka