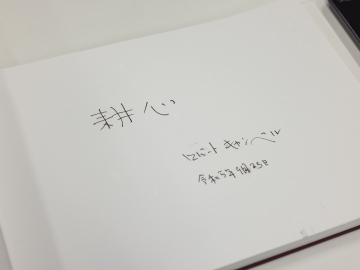

Congratulatory Address by Professor Robert Campbell

Fri, Sep 29, 2023Robert Campbell

University professor at Waseda University

An advisor for The Waseda International House of Literature (The Haruki Murakami Library)

The first words all of you need to hear today should be shouted out in a clear voice: Congratulations to each and every one sitting in front of me! Unqualified, unvarnished, spelled out in caps and crystal clear CONGRATULATIONS!

First of all a shout-out to the 80 percent of the incoming fall class of 2023 who’ve actively chosen to study here in Japan, so far from friends and family and everything you know, in order to learn, to grow, to connect, and to see the world and your place in it through a lens and through a language that will serve you in ways none of us can predict beyond decades of accelerating global change. The simple fact that you are here today is cause for jubilation: you’ve all studied really hard, at school, at home; and many of you worked, and are still working, for wages in order to get here in the first place.

Congratulations also to each and every one of you for being the first in three years to actually attend this matriculation ceremony in person. We’ve all made huge sacrifices in our lives and in how we’ve studied throughout the Covid 19 pandemic. I’m sure some of us are still struggling to this day, trying to make up for lost time and for deep disturbances, reflected globally in the decline of students who, for economic or whatever reasons, actually enrolled in college over these last three years. Many of you were probably forced to postpone your own travels for a year or more because of border restrictions into Japan or because of difficulties leaving and returning to each of your home countries. Congratulations for persevering, and for preparing to cross the ocean while public health restrictions for many of you were still in force.

According to one large survey of colleges made in the US in 2021, 9 out of 10 college students said they’d struggled with isolation, anxiety and a lack of focus during the pandemic. More recent surveys show us that about 80 percent of seniors graduating this year feel that the pandemic has affected their readiness to work after graduation. During Covid, not being able to socialize, to talk to new people with differing outlooks and orientations, actually physically moving among them from dormitory to classroom to laboratory, then going out at night and weekends to chill or to volunteer or participate in some sort of organized activities, left them anxious about taking on actual responsibilities in the workplace. It looks like the entering class of 2023 will at least be able to avoid some of the anxiety caused by enforced social isolation.

Waseda University is a great place to study, because of the faculty and because of the diverse body of students for sure; and as you’ll discover, the facilities are amazing also. I myself am a professor of the humanities, which means I spend a lot of my time searching for old books in the stacks of the Central Library or watching century-old films at the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum. Sometimes you can find me drinking coffee while I read a translation of Haruki Murakami’s novels at our brand new Waseda International House of Literature, just a few minutes’ walk across campus from here. The donuts are super delicious by the way – I recommend you try them as soon as you can with your friends.

One other amazing thing about studying or working here, though, is the fact that we’re standing – or today, sitting – in the middle of Tokyo, right among some of the oldest surviving parts of the Shogun’s historical capital, Edo, and at the same time surrounded by the hustle of ultramodern Tokyo life. On a sunny day between classes, try walking ten or fifteen minutes straight north from campus. The area above Kanda River is dotted with hills, some so steep they were given names like Munatsuki-zaka or “Chest Pounding Slope.” Samurai lords built their grand manors and gardens on hills way above the town as sanctuaries away from the poor public hygiene of so-called “downtown” or shitamachi – literally “lower-land” – neighborhoods, which were densely populated by merchant and artisan classes. Infectious diseases were one of the leading causes of mortality in early modern Japan. Measles epidemics, for instance, washed over the urban population every twenty five years or so, and, to paraphrase one novelist writing about a surge of infections in 1803, the deadly disease made no distinction between lords hiding behind their bamboo curtains, and the men down in the stables who tended to their horses.

The noble samurai men, women and children who walked the streets around us in Waseda two hundred or three hundred years ago would reside here and network with other members of the governing class through sankin kotai, a unique Japanese political and cultural system by which Tokugawa period provincial lords were required to spend every other year in Edo – our present day Tokyo – to show their loyalty to the Shogun and occasionally to attend his council at the palace. Often these samurai families would build their own private academies on the grounds, with libraries, medicinal herb gardens and aviaries where younger members of the domain could study and sometimes prepare for a life of learning and education. Many of the greatest poets and painters of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century long era of peace before the 1868 Meiji Restoration would gather here to create and to exchange ideas and information across class lines.

The physical environment we exist in is, in other words, never quite an accident, some random result of financial transactions made faraway. Rather, we can often find threads of causality and cultural affinity between what we accept as atarimae or the obvious, and what occurred at the very place we’re standing, decades or maybe even centuries ago.

Studying at the university is one great way to gain many of the skills we need in order to build our careers, and to make important decisions as voters, consumers, parents or teachers of the next generation to follow us here on this impossibly polarized, endangered planet. And there is a synergy involved here, an opportunity for each of us gathered today, to expand and to cultivate our understanding of this world through direct contact and action – whether that action be a simple walk by yourself up a steep hill to retrace and envision the lives of men and women who walked on the same path hundreds of years ago, or to reach out even further, beyond the campus gates, into areas of society we’ve only heard of or glimpsed at through digital space.

Let me tell you about a faraway journey I myself made recently, and introduce you to one of the people I met on the way.

As we all know, Russia’s war in Ukraine has been going on for more than a year and a half. Over ten thousand civilians have been killed in their homes, on the road and in shelters by missiles and drones, and over 6,000.000 Ukrainian citizens have had to flee their homes, internally displaced, or fleeing abroad, since February of last year. In fact the four students from Ukraine who join us this year and are with us today were displaced by the aggression, and have spent the last year studying Japanese language so that they can be with us today.

I’ve spent the last few months translating, from English into Japanese, a book of short personal accounts which were given by over seventy men and women who faced and were luckily able to escape from the violence of war. Most of them fled to the west, through a beautiful ancient city near the Polish border called Lviv, which for hundreds of years has been the urban conduit between eastern regions and Central or Western Europe. Local volunteers from Lviv gathered day and night in the cold after the invasion began to greet the displaced, to feed them, to house them and to see many of them off to points further west. Among them was one man, a poet, who volunteered for the army in late February, but was rejected.

He was rejected, so what did he do? He decided instead to care for those who arrived in his home town, despondent, hour after hour. The man stood waiting for refugees at the Lviv Central railway station, greeting passengers day and night as they came down from the train with hot tea, sweets and medicine. Most of them were women bringing along children and their pets in cages. As he tended to each of them in the freezing cold, he would listen carefully to what they had to say. The stories that each of them shared with a stranger, whose path they crossed almost accidentally that day, would soon form the body of the book I have translated, which in English is titled “A Dictionary of War.” .

The poet – his name is Ostap Slyvynsky – he helped these strangers overcome what must have been a crippling anxiety, collecting each of their stories in the cold, and arranging them alphabetically by title, which he chose from words in each story that encapsulated the most important item or idea that he or she brought from the scene of disaster. I visited Lviv in June, and was able to spend two weeks visiting and talking with those who had fled their homes.

Ostap wanted to give shape to his collection of testimonies, so he chose the form of a dictionary, so that future generations could look back and see precisely how war and the threat of annihilation bends and turns upside down the meanings of the very words we use every day. One story was told to him by Anna, a woman living in Kyiv who fled west to Lviv early after the assault. One of Anna’s most precious, private memories, the sound of an apple falling on the ground, was twisted into something unrecognizable by a missile attack she endured late at night, at home, in the capital. Let me read you the English version.

Apples

“That night I fell asleep in the bathtub, in a bucket of blankets and pillows, listening to the most powerful explosions here since the beginning of the war.

Long ago, in my past life, I fell deeply in love. The two of us went to a house in the Carpathian mountains for the first time; it was deep in the autumn, we were falling asleep in an attic, in a bed that was not much more comfortable than my bathtub, and I was listening to apples hitting the ground everywhere in the garden. They were slamming and slamming, large and ripe, at a measured pace, throughout the night. I was so happy.

Now, I was falling asleep to the sound of missile blasts, and I heard those apples. I just wanted so badly for those garden apples to be hitting the ground all around us now.”

“Precarity” is a word we often use these days in English, to denote a sense of imbalance or existential anxiety because of something that’s gone terribly wrong, and is way beyond our control to stop, like climate crisis, or pandemic lockdown or a full-front invasion of your country in the dead of winter. Ostap’s “Dictionary of War” invites us to experience, at second hand, particular moments in time and space, by showing us how the threat of violence can change the very meaning of words used to manifest and present ourselves day by day.

Japan, for some of us here today, is a sanctuary. For the majority, though, living and studying here is simply life – a set of givens, obvious in the contours and daily challenges they bring us – the rain, the beautiful sunsets, the bright flowers we’ll see families bringing today, on the autumn equinox, to temple gravesites in order to honor their ancestors.

What words would you use to describe your sense of balance or imbalance as you sit here, about to make the first step into your new journey? Can you imagine yourself walking beside, trying to listen to somebody just like yourself, who came to this spot from faraway maybe two or three hundred years ago to learn about the world and his place in it? How about someone five or ten years in the future, who’s suffered the fire of war and needs help rebuilding her community? What words would you offer them; what questions would you ask?

Words can be translated into action, and actions have the power either to harm or to heal us. The next four years will lead you towards a career, and will help shape your view of the world in ways, hopefully, that will bring you closer to the joys and to the challenges felt by others at great distances of time and culture and space. I say hopefully because the world will be waiting for these words of yours, and certainly for the actions you take. Good luck every step of the way.

Profile

After graduating in 1981 from the University of California, Berkeley, Professor Robert Campbell received his PhD from the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the Harvard University. He moved to Japan in 1985 as a research student at Kyushu University’s School of Letters, and became a assistant professor there. Subsequently, he was an assistant professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature, and was appointed to associate professor at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 2000 where he became a professor in 2007. In April 2017, he was appointed as the director of the National Institute of Japanese Literature. He was appointed to his current positions in April 2021.