“The New Normal” of the Feminist Movement in Indonesia

Fri, Oct 30, 2020-

Tags

“The New Normal” of the Feminist Movement in Indonesia

Professor Ken Miichi,

Waseda University Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies

In a normal year, when the university holidays start, I would immediately head to Indonesia for fieldwork. However, this summer I couldn’t go outside of Tokyo, much less outside Japan. It was frustrating for me, but even in these times, the social activism in Indonesia I saw on my screen was energetic. Labor unions and human rights groups are continuing their demonstrations with masks. In early October, the Indonesian parliament passed a set of laws to improve foreign investment, but these laws actually limits the rights of workers. As a result, large-scale and fierce protests have taken place. A phenomenon that’s new in this pandemic is the announcements on social media timelines about webinars using Zoom and Instagram. Even just the ones on feminism which I am researching are taking place almost every day – not exaggerating.

What kind of new meaning could the discussion on these webinars give to social movements? This column explores, through the example of Indonesian feminism, the “new normal” created by webinars.

Fight Over Proposed Sexual Violence Law

In Indonesia, since the political turmoil and democratization of 1998, there has been progress in organizing feminist activism for protection of women’s rights and gender equality. (*1) Especially distinctive is the development of Islamic feminism, which, with devotion to Islam as a given, uses its principle of equality as a weapon. To change the mindset of a nation which is 90 percent Muslim, a religious underpinning is essential.

In recent years, the feminist movement has been consistent in calling for passage of a sexual violence law. Just from reported numbers, there are 430,000 cases of violence against women annually in Indonesia (2019), and the number is rising each year. Now, isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic has raised fears of further increases in domestic abuse and sexual violence.

Effectively written by feminist activists, the proposed sexual violence law is a reaction to existing criminal law, which is seen as insufficient in areas such as scope of punishable offenses, measures to protect victims and programs to rehabilitate perpetrators.

A promotional pamphlet for the proposed law says the following. “Passing of the sexual violence bill will lead to greater welfare for the citizens as humans, endowed with dignity by Allah, the Creator. Sexual violence is a violation of human dignity. The perpetrator’s attitude is that of a male or female lacking humanity, and the victim suffers inhumane treatment.” Based on the Quran, it argues that humans are special beings created by God, and that men and women are equal in that nature. (See Figure 1)

(Figure 1) “Why must the sexual violence law be supported?”

Source: Jaringan Kerja Prolegnas Pro-Perempuan (JKP3), “Mengapa DPR dan Pemerintah harus segera membahas dan mengesahkan RUU Penghapusan Kekerasan Seksual Vol.1-3,” 2019.

Feminist activists anticipated passage of the sexual violence bill in the parliamentary term ending September 2019, but the prospects quickly faded as it became a political issue in the runup to the April presidential election. Conservative Islamic forces opposing the bill created fake news, labeling the bill as “enabling free sex and LGBT,” “destroying morals,” and “anti-Islamic” in social media, and many people believed it. (*2)

Politicians of the government and opposition alike shrank from supporting the bill, and their inaction tabled it. Then in July 2020, as parliamentary activities were limited by the COVID-19 pandemic, the sexual violence bill was removed from the National Legislation Program (Prolegnas) priority list, further reducing the likelihood of its passage. (*3)

Islamic Feminism Courses Online

In response to this situation, the feminist movement ran a campaign, including numerous webinars, to demand passage of the sexual violence bill. In fact, webinars fit well with this kind of advocacy campaign. Social media communication is dominated by short messages. They are dressed up, diffused with one click and delivered to our fingertips. Even if the basis in reality is weak, a message with strong, visceral appeal can spread like a virus. The failure of the sexual violence bill last year was a case of getting tripped up by this feature of social media.

Conversely, longer discussions have been done mostly off-line. Seminars have been webcast too, but they tend to be long-winded and audio quality poor, hindering the message. Webinars are a big improvement. The talk tends to be relatively shorter and more succinct. There is more interaction, and the barriers to participation are lower, for presenters too. Above all for Jakarta, people don’t need to fight its world-class traffic jams to gather in one place. (*4)

Utilizing these features, the sexual violence bill webinars brought together not only “insiders” like its activists, but also politicians and others. Before, as far as I know, politicians were the objects of lobbying, but didn’t participate in the feminist activists’ open conversations. When direct lobbying is difficult, pulling politicians into the open conversations is a great idea.

While most webinars are one-time affairs, the work of scripture (tafsir) scholar and Islamic feminist Nur Rofiah stands out. While teaching at the Islamic University of Indonesia’s graduate school, she has also tutored students in gender equity and Islam at her home. Last year, she began conducting workshops around the country, targeting students at provincial universities and Islamic schools in over 20 locations. The programs deepen understanding of Islamic feminism, the intellectual foundation of the sexual violence bill.

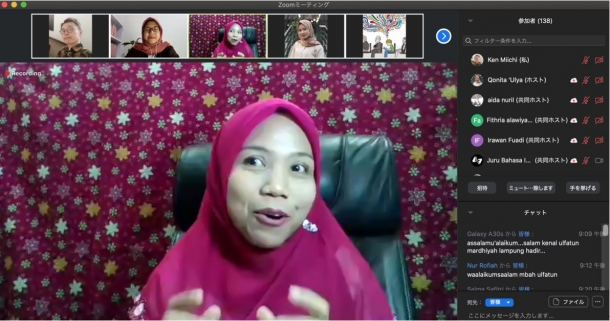

(Figure 2) Nur Rofia on a webinar. Photo by author, used with permission.

The workshops are still continuing on Zoom. With themes such as “The relationship between genders in Arabic” and “Islam as a doctrine preaching women’s rights,” the free online courses comprise six sessions of 2.5 hours each. For example, a June 26 introductory course explained the changes in fatwas (official answers to believers’ questions on interpretation of Islamic law), which in the past have been almost exclusively issued by male scholars (ulamas). Specifically, it is about women joining men in the legal debate, as well as having women be not just the subjects of legal interpretations but reflecting in future legal interpretations their physical experiences and experiences of injustice. A second series of the same content began at the end of August. The first series had 500 people registered and the second over 850. By moving online (and with sign language interpretation), the audience has grown dramatically.

As shown above, the webinar has many advantages over conventional advocacy methods. It is a new tool of social activism which will surely continue in the “post-COVID era.” The flexibility to cope with this situation, as well as the organizational and human network which can run webinars day after day, are resources of the Indonesian feminism movement.

Notes:*

- In the riots during the May 1998 turmoil, there were incidents of organized rapes of women. This became the impetus for establishing the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komisi Nasional Anti Kekerasan terhadap Perempuan), which is now an institutional pillar of the feminist movement.

With the great expansion of political freedom, many NGOs have been formed. In 2005, a collective of 41 organizations formed the Network for Pro-Women National Legislation Program (Jaringan Kerja Prolegnas Pro-Perempuan: JKP3). It is lobbying the parliament and government agencies for legal measures to protect women’s rights. - In Indonesia, prejudice against homosexuals and other LGBT people is deeply rooted and tolerance is extremely low. However, homosexuals have been a normal part of urban nightlife and supporting roles in movies. The term “LGBT” has entered the lexicon, but instead of sexual minorities, it is often used to refer to the political movement which supports them. And conspiracy theories abound that the movement is an immoral cultural invasion from the West. This tendency also applies to feminism. For analysis of the discourse around LGBT, see: Michael Ewing, “The use of the term LGBT in Indonesia and its real-world consequences,” Melbourne Asia Review, May 6, 2020.

https://melbourneasiareview.edu.au/theuse-of-the-term-lgbt-in-indonesia-and-its-real-world-consequences/ - For details about the battle over the sexual violence bill, see: Ken Miichi, “Post-Islamism Revisited: Response of Indonesia’s Justice and Prosperous Party to Gender Issues,” The Muslim World (forthcoming).

- The challenges, as for online university courses, are internet access and difficulty of informal communication among participants.

Author’s Profile

Born in Chiba and raised in Kobe, Ken Miichi completed the PhD course (Doctor of Political Science) at Kobe University’s Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies in 2002. After 3.5 years at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, 1.5 years at the Embassy of Japan in Singapore, and 10 years at Iwate Prefectural University, Dr. Miichi became Associate Professor at Waseda’s Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies in 2017 and Professor in 2019. He specializes in contemporary Southeast Asian politics and comparative politics, focusing on Indonesia’s Islamic movement.

His major publications include Shinkotaikoku Indonesia no Shukyoshijo to Seiji [Religious Marketplace and Politics of the Emerging Power Indonesia] (NTT Publishing, 2014), Dynamics of Southeast Asian Muslims in the Era of Globalization (Co-editor Omar Farouk, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and Social Media Jidai no Tounanasia Seiji [Southeast Asian Politics in the Social Media Era] (Co-editor Yuka Kayane, Akashi Shoten, 2020).