【Waseda University Podcasts: Rigorous Research, Real Impact】 Stories of Statelessness: An Auto-Ethnographical Account Part 1

Tue, Nov 5, 2024-

Tags

About the Series

For the newly launched “Rigorous Research, Real Impact” English language podcast series, seven knowledgeable Waseda researchers active in the fields of the social sciences and the humanities casually converse with the MC about their recent, rigorously conducted research, the positive impact it has on society, and their thoughts on working in Japan at Waseda in short 15 to 30 minute episodes.

For the newly launched “Rigorous Research, Real Impact” English language podcast series, seven knowledgeable Waseda researchers active in the fields of the social sciences and the humanities casually converse with the MC about their recent, rigorously conducted research, the positive impact it has on society, and their thoughts on working in Japan at Waseda in short 15 to 30 minute episodes.

It’s a perfect choice for listeners with a strong desire to learn, including current university students considering further study in graduate school, researchers looking for their next collaborative project, or even those considering working for a university that stresses the importance of interdisciplinary approaches.

Episode 1: Stories of Statelessness – An Auto-Ethnographical Account Part 1; From Statelessness to Advocacy

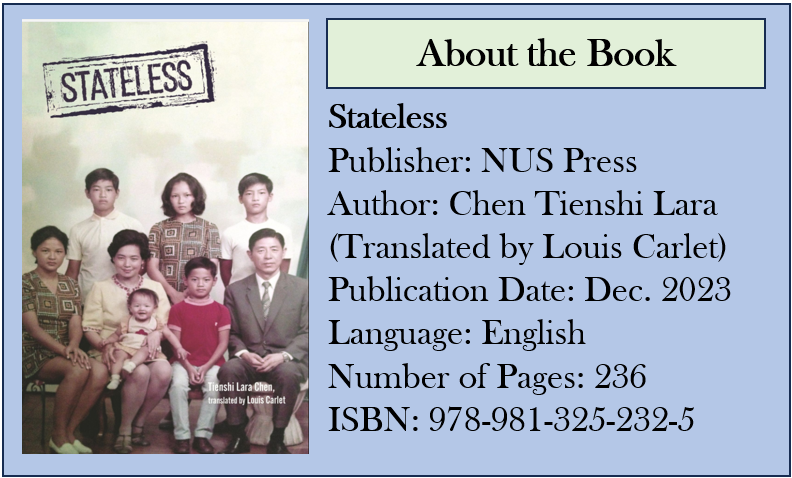

Waseda University Professor Lara Tienshi Chen (School of International Liberal Studies) serves as the guest expert for the first two episodes of “Rigorous Research, Real Impact”. Professor Chen was raised in Yokohama, Japan but spent more than 30 years of her life categorized as “stateless”. In episode one, she shares her personal experience living as a stateless person and recounts how this influenced her decision to research statelessness, culminating in her book “Stateless.” Prof. Chen then connects her life experience with her current work at Waseda, where she continues to positively impact society by advocating for stateless people both in Japan and across the world.

Waseda University Professor Lara Tienshi Chen (School of International Liberal Studies) serves as the guest expert for the first two episodes of “Rigorous Research, Real Impact”. Professor Chen was raised in Yokohama, Japan but spent more than 30 years of her life categorized as “stateless”. In episode one, she shares her personal experience living as a stateless person and recounts how this influenced her decision to research statelessness, culminating in her book “Stateless.” Prof. Chen then connects her life experience with her current work at Waseda, where she continues to positively impact society by advocating for stateless people both in Japan and across the world.

Links to Episode 1

About the Guest:

Professor Chen obtained her PhD in International Political Economy from the University of Tsukuba. She went on to conduct research at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Harvard University, and the University of Tokyo. She worked for the National Musuem of Ethnology, Osaka prior to joining Waseda’s School of International Liberal Studies in 2013. Professor Chen is also the founder of the NPO Stateless Network and works closely with the student volunteer club Stateless Network Youth.

About the MC:

Kaivaliya is an India-based MC.

Episode 1 Transcript

Kaivalya (MC) (00:05):

Hello and welcome to the inaugural episode of Waseda University’s English podcast series, “Rigorous Research, Real Impact.” I’m Kaivalya, your host for this episode.

In this series, we bring you insightful conversations and stories from Waseda’s vibrant academic and cultural community. Today, we are diving into a topic that is often overlooked in the headlines, and that is statelessness. While mainstream news is filled with stories of conflicts around the world, we don’t often hear about the conflicts that shape the lives of people on the ground.

And so, in this episode, we attempt to focus on these unheard voices who find themselves stateless for a variety of complex reasons, which may include conflict or changes in the nation’s policies, as well as deliberate choices driven by ideological differences with the states that grant citizenship. To discuss this issue in depth, we have Professor Lara Tieshi Chen with us today. She is a Professor at the School of International Liberal Studies at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan.

Having personally experienced statelessness for over 30 years, Professor Chen advocates passionately for stateless communities. She recounts her life story and the real stories of people who have experienced statelessness in the recently published translation of her book, ‘Stateless.’

In the book, Professor Chen takes us on a journey from her childhood to growing up as a stateless individual in Japan and the challenges she faced. We learn how she became a strong supporter of stateless individuals and about her awareness efforts. So, without further delay, let’s jump in.

A very warm welcome to you, Professor Chen, and thank you for joining us today. I recently read your book, Stateless, and found your personal story to be incredibly moving. In the book, you examine a little-known but persistent issue in today’s world, which is statelessness. So, to start with, could you just help our listeners understand what statelessness is?

Professor Lara Tienshi Chen (Guest) (01:59):

Thank you. Thank you very much for reading my book. And also thank you for telling me that you were moved by the book. I’m so happy to hear that.

First of all, we have to share the definition of statelessness or stateless people. They are the people not recognized to be nationals of any state. So according to the UNHCR, there are 4.2 million people in the world reported as stateless. However, the actual number is estimated to be higher, I think it will be over 10 million. The important thing is that the term “stateless people” includes those whose nationality is registered as undefined on their identity documents issued by the country of residence. There are also situations often observed in Japan where the section for displaying nationality or region on a person’s identity document indicates that the person is a national of country A when in reality the person is not registered as a national by country A. This leaves the people in the situation of statelessness or where their nationality is unclear. So, I think that’s why the number could be much higher.

Kaivalya (MC) (03:35):

Okay, so a large part of your book, of course, talks about your own experience of being a stateless individual for almost 30 years. And of course, that would probably shape your identity growing up. Could you also tell us a bit about that experience about how this all shaped your identity?

Prof. Chen (Guest) (03:53):

Yeah, I lived as stateless person for over 30 years. I was born and raised in Yokohama to Chinese parents. My father is 103 years old today. He was born in Manchuria, and he experienced transitions in government many times. My parents escaped the hardships of World War II and the civil war in China and moved to Taiwan, then moved to Japan in the 1950s. In 1972, Japan normalized diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China while it broke with the Republic of China, Taiwan. My family became stateless aliens in Japan with this event in 1972 when I was just a one-year-old. And our family was stateless aliens with legitimate residence status. Therefore, legally, I could go to school and enjoy health insurance. However, because social awareness of statelessness is very low, I experienced a lot of discrimination and hardship. For example, when applying to a private elementary school, teachers were hesitant to accept me because I was stateless. And when I was studying in university, I needed to rent an apartment, but the landlord hesitated because of statelessness and asked for guarantors and the bank balance certificates of my guarantors. It was hard for me to apply for scholarships and, of course, get a job as well.

Kaivalya (MC) (05:50):

Right. And that would definitely have an impact on one’s sense of identity or one’s sense of self.

Actually, that leads me to the next question that I wanted to ask, because from there, your journey, you become an advocate for the stateless people. You’ve become an author, a filmmaker, and you do talk about how difficult it was to navigate these discriminations or challenges along the way.

So, what I wanted to ask is what motivated you, actually, to keep at this path and pursue this and just be an advocate for statelessness issues around the world?

Prof. Chen (Guest) (06:21):

Yes, being stateless, the most unforgettable experience was when I traveled overseas. I could not enter any country. Neither Japan, where I was born and living, nor Taiwan, where my parents were from. I was just stuck in the airport. At that time, I actually realized that borders exist, and I experienced firsthand that I am a stateless person. Until then, I did not really know, and I did not understand what is stateless and what is written on my ID card. So, I did not feel I belonged to Japan, so I decided to go overseas and study doing my Ph.D. research in the US. And in the US, I applied to work in the UN because I thought that the UN is a transnational entity. However, I could not be employed because I was stateless. And the staff in the UN told me to get Japanese nationality and apply again.

So, after that, I thought I should study about myself, about statelessness. Around 1997 or 1998, I looked up statelessness in the library and could not find any literature on the subject. And I did not know which government to consult with or who to share with. And I was really at a loss. And I thought it was really strange. Why? I could not understand why they were more concerned with my nationality than with me as an individual. So, I wanted to meet more stateless people and learn more about its reality. I thought it was important to project it in a documentary film and communicate it to more people in an easy-to-understand way and let more people know the reality of stateless people. I wanted to share more about the lives of stateless people and also wanted to establish a “yoridokoro” in Japanese, I don’t know how to translate it into English, but it’s like I wanted to establish a base where stateless people can feel at home and that led me to establish the NPO stateless network.

Kaivalya (MC) (09:18):

Thank you so much for that. And I do want to talk about the stateless network a bit later on. But what you spoke about just now, you know, for me as well, the book was quite revelatory. And I think a lot of people will read it too because it’s not a topic that’s spoken about very much. We don’t really understand the scale of it. But I know you did talk about a few UN numbers.

Would you be able to shed light on how serious you think or how prevalent the issue is in today’s world? Especially since you’ve traveled around a lot, not just in Japan, but in other countries as well. So, could you talk a little bit about stateless individuals in different parts of the world you visited or how prevalent using the issue is?

Prof. Chen (Guest) (09:57):

Okay, stateless people are so varied. So, you know, every individual has a different reason to become stateless. Some people became stateless because of the contradictory laws in the nationality law, and determination procedure, making them ineligible for acquiring the nationality. Some people lose their nationality and became stateless because of the disintegration of a state or a change in the ruling regime of the country, which we can see many from after the Soviet Union or after Yugoslavia and so on. And in some cases, people may not be re-granted a nationality, or they may lose their nationality because of discrimination against minority groups to which they belong. For example, everybody knows the case of the Rohingya or Druze people. And also, there are Tamil people in Sri Lanka who have lost their nationality. And the system for determining a person’s nationality can be divided between those where the criterion for determining nationality is the country of birth and those where it is the nationality of the parents that determines nationality. It is also often the case in many countries that both criteria are not taken into consideration for the determination of nationality. And in reality, in Japan, we have many stateless children born out of wedlock. For example, a Japanese father and a Filipino mother, are not legally married. Before 1984, there were many US military personnel and Japanese woman who had a baby and the babies ended up stateless. So yes, from these cases I found that there are many varieties of stateless people, and the reasons are also different.

Kaivalya (MC) (12:29):

Thank you so much, Professor Chen, for explaining that. I’d like to move on to talking more about your research and work at the university because you have dedicated a lot of your time there to spreading awareness about statelessness and even providing a platform for stateless individuals. So, can you talk a little bit about your work at Waseda University and the research that you do?

Prof. Chen (Guest) (12:49):

Yes, first of all, more people need to know the real situation of stateless people, you know, statelessness. I try to create opportunities for students to think about statelessness and also question nationality, which people take for granted. So, I try to hold a photo exhibition or try to invite stateless people to come and give a talk, events, etc. And this year we held an international symposium titled “Understanding human rights of stateless people in the real life context in the Asian Pacific in commemorating the 70th anniversary of the 1954 convention relating to the status of a stateless person.” This was held on June 1st at Waseda, and we invited experts on statelessness from Thailand, Malaysia, and directors of NGO groups that support stateless children in the Philippines and experts from UNHCR stateless division as well as stateless people to join this event. The goal of our event was to raise awareness of statelessness in general and to exchange knowledge, experience, highlight good practices, positive development, and accumulating in Asia, including Japan, and share challenges and to promote positive development, including Japan’s Establishment of Statelessness Determination Procedure, or access to the 1954 convention on the Stateless Person, because Japan is not yet a member of the convention, and also to build the capacity youth group through collaborating organization with Stateless Network Youth, building momentum for the final year of the UNHCR “I Belong” campaign. Yes, that’s what we did recently.

Kaivalya (MC) (15:16):

That’s some really amazing work, Professor Chen. I’m sure our listeners have learned a lot today about statelessness and about the awareness you and your team are raising for complex issues like this. The awareness you’re spreading, I think, is so important to build empathy, question norms, and change perspectives. So hopefully it can eventually lead to policy reforms and maybe a more equal world. So yes, thank you once again for sharing all of these insights with us.

With this, we will wrap up the first part of our conversation with Professor Chen. Her account and experience have been incredibly moving and encouraging, and we look forward to hearing more about her personal journey as well as her research in the second half. So, stay tuned for part two, where we will dive into Professor Chen’s impactful work at Waseda University and explore her ideas on how best to support stateless communities. Don’t forget to subscribe to “Waseda University podcasts” to keep up to date on the latest “Rigorous research, Real impact.”

Until next time, take care and stay curious.