Waseda Frontline Research Vol. 7, Part 3 – Can science win medals? Using science at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics!

Tue, Jan 26, 2016-

Tags

Exercise physiology and biomechanics researcher

Professor Yasuo Kawakami, Faculty of Sport Sciences

“The key to a top athlete’s “best performance” is how they use their power” (Kawakami)

When top athletes deliver incredible performances that excite people around the world at events such as the Olympics, their feats may not be the product of just the body and mind, but of the senses as well. Many athletes experience a type of supernatural experience upon victory often referred to as “being in the zone.” What relationship does “being in the zone” have with athletic ability? To discuss this topic, we spoke with former sports commentator and Kansai University Associate Professor Yukiko Shiki (Faculty of Health and Well-being) and Waseda Professor Yasuo Kawakami.

“The key to a top athlete’s “best performance” is how they use their power” (Kawakami)

Ms. Shiki: My research focuses on “the zone” and the senses as they relate to various sports fields. Survey results of top athletes we have interviewed suggest that they are “in the zone” when performing at their best. For example, Olympic diver Ken Terauchi once said, “When I was climbing the stairs before competing, I could see my own foot prints in front of me.” (from Yukiko Shiki’s book, “What the Senses of Extraordinary People Tell Us About the Law of the Zone: 14 Articles on Obtaining the Ultimate High in Sports” (Shodensha, 2012)). Many believe that when an athlete is “in the zone,” they attain a state of absolute selflessness, free of all constraints. Professor Kawakami, I know that your research focuses on the visualization and quantification of physical performance in various ways, but what do you think of the “zone” that so many athletes experience?

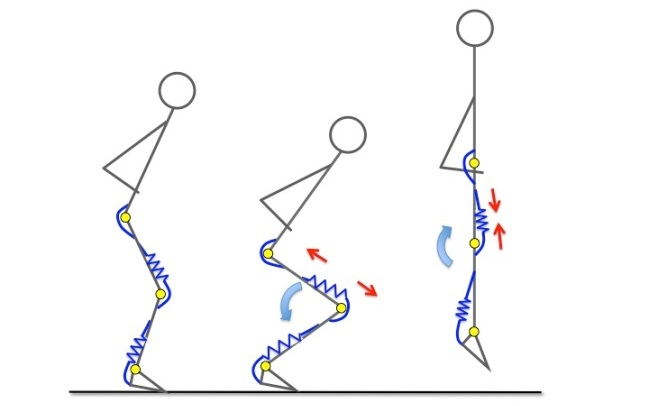

Mr. Kawakami: It is interesting. As the contraction of many muscles throughout the human body efficiently work with the tendons connected to bone, a powerful multi-joint combination movement occurs. An athlete’s “best performance” is the result of a combination of these structures, along with a skillfully timed process that switches between them. The amount of power exerted is not the only factor at play. Rather, the way in which power is used is the key to delivering such a performance. Science has helped us understand this.

Figure 1: As the contraction of muscles throughout the human body efficiently coordinates with the tendons connected to bone, a powerful combination of multi-joint movement occurs (source: Yasuo Kawakami)

For example, a golfer’s swing involves a chain of movements including a wind-up, a swing, and a follow-through. The muscles and tendons used in this process change rapidly. The smallest error in timing will result in an insufficient exertion of power. Even for highly skilled golfers there is a “wave” of movement to their performances. “The zone” is thought to be the result of a skillful utilization of this timing process.

Ms. Shiki: It is believed that athlete’s use their senses to process information as effectively as possible while in “the zone.” However, some athletes say that in “the zone,” some senses are dulled while others are enhanced. For example, some say they have seen the trajectory of a ball in the form of a white line or light but could not hear the sound of cheering spectators. Others say they would tune out booing but be able to recognize pitches of certain voices that would help them win. This is known as the “cocktail party effect,” or the ability to drown out unnecessary noise to focus on important matters at hand (taken from Yukiko Shiki’s book, “Coach Takeshi Okada’s Thoughts on Sports and the Senses”, Nikkei Publishing Inc., 2008).

Mr. Kawakami: This is only conjecture, but perhaps while in “the zone,” an athlete is entering a preparatory state in order to replicate a past best performance. In order to replicate the movement program of that past performance, perhaps it is necessary to regenerate the various sensory conditions of the body at any given time, from vision, hearing, and muscles. It may be possible that the athlete is shutting out all unnecessary information at this time. When a professional golfer is in “the zone,” the hole looks abnormally large. By training various senses, athletes may have developed a way of recalling their best movement programs.

Ms. Shiki: It is believed that this includes subconscious actions and everyday routines. Many athletes fall into the trap of searching for a way of “entering the zone,” but it is more important to define one type of aesthetic foundation for their movements. If we can establish common traits among senses of top athletes in the zone, it will greatly benefit the sports world and society as a whole.

Mr. Kawakami: The concept of finding a way to recall one’s best performances sounds like an interesting research topic. If it can actually be worked into a methodology, perhaps a training program could be formulated for getting athletes into “the zone.” I am conducting research that I like to call “winning medals with science,” and I hope we will both be able to contribute something positive at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Yasuo Kawakami, Professor at Waseda University Yukiko Shiki, Associate Professor at Kansai University

“The fight-or-flight response is triggered by shutting down the brain’s limiter” (Kawakami)

Ms. Shiki: I hope so too. By the way, I believe you have been researching the “fight-or-flight response” and how it can be applied to the Tokyo Olympics. Some people refer to the abilities triggered while in the zone” as the “fight-or-flight response,” but looking through the lens of your research, how would you describe “the zone”?

Mr. Kawakami: We do not have an accurate understanding of its relationship with “the zone,” but the “fight-or-flight response” teaches us that humans have a reserve of power, even when they are trying to exert all of their strength.

Nerves control muscles, with dozens or even hundreds of cells responsible for a single muscle in some cases. Humans are able to increase the number of working nerve cells to adjust the level of power exerted, so if we are able to excite all of these nerve cells, we would theoretically be able to use 100% of our strength. Do you know about the “shouting effect”?

Ms. Shiki: Yes, track and field athletes that throw events often shout loudly during their performance to produce as much power as possible.

Mr. Kawakami: Precisely. Humans can consciously increase their excitement levels. This increases the number of working nerve cells, which enables them to exert a significant amount of strength. Even so, it is still not possible to excite 100% of them. Sleeping nerve cells are in the body as well.This is why that when we used electrical stimulation to excite sleeping nerve cells in an experiment, we found that more strength was exerted that normal. This extra strength is the same that we see during a “fight-or-flight response.”

Ms. Shiki: So that means one way of getting into “the zone” is to find a method that can excite sleeping nerve cells. Am I correct to say that normal brain control shuts down during a “fight-or-flight response”?

Mr. Kawakami: That is correct. Control is not completely shut down but the brain’s “motor area” used for motion control has increased excitement levels that activate sleeping nerve cells. As a result, people are able to exert an incredible amount of strength to lift cars and other such feats. However, the brain usually has a limiting function to protect the body from damaging itself with such tremendous strength.

Although I am not sure of the connection, perhaps the “fight-or-flight response” has some sort of secondary relationship to being in “the zone.” The motor area’s excitement levels are related to movements within the brain and increases accordingly. For example, when nerve cells of the brain’s prefrontal area are active, a motivation mechanism increases activity in the motor area. Ultimately, activity in the motor area is what moves the body, but other parts of the brain are influential as well. This could be “the zone” that some athletes experience, and that is stored in the prefrontal area, the cerebellum, or the area that controls the memory.

“The zone gives us a glimpse into unknown human potential and the greatness it brings.” (Ms. Shiki)

Ms. Shiki: Every time I hear a story from someone that has experienced the zone, it enhances the mystical aspect of an unseen world. Does your research incorporate this mysteriousness?

Mr. Kawakami: All of it is mysterious. For example, an ultrasonic device can only measure one muscle. I do not even know what is happening with other muscles. This measurement method has its limits. To tell you the truth, with complex sports movements, and even something as simple as walking, we know very little about the muscles related to those movements, including how they are triggered.If we are unable to simplify those movements and measurement targets to perform experiments, we will not be able to acquire the data needed to formulate scientific papers. The scientific community has always suffered with the dilemma created between the mystery of the human body and scientific proof. As an organism, humanity is generously redundant, but we still struggle to grasp it. This is the mystery we need to unravel. How about you Professor Shiki?

Ms. Shiki: I have been working to illustrate the sensory mechanisms involved when getting into “the zone,” and attempting to quantify human senses. However, these senses cannot be quantified or or given true meaning with words, so I tend to lose a grasp of the essential points through quantification, and lose out on the true senses. This is the sort of contradiction I run into. When researching senses and “the zone,” the deeper I investigate, the more I learn about the personal, deep inner world of humans, which most people do not think about on a regular basis. Yet at the same time, I feel that I am beginning to understand a part of the outer world, namely the mechanisms and laws of our vast universe. When I feel the potential of the research in this way, I find it easier to understand depending on its visualization.

Mr. Kawakami: It is hard for us humans to perceive information other than what we see with our eyes, and hear with our ears. Perhaps there is a lot of information out there that cannot be detected with our sensory organs.

Ms. Shiki: I agree but I believe we can perceive and utilize the innate senses within all of us.

The next and last article in this volume is “Creating a healthy society through research in biomechanics,” in which Professor Kawakami uses his research to discuss Japan’s aging society and future prospects.

Associate Professor Shiki and Professor Kawakami stroll through Waseda University’s Tokorozawa Campus. It is Ms. Shiki’s former school, and where Mr. Kawakami currently conducts research

Profile

Yasuo Kawakami graduated from the University of Tokyo with a degree from the Faculty of Education’s Division of Physical and Health Education (Physical Education Course) in 1988. In 1990, he acquired a Master’s Degree from the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Education and withdrew from the doctoral program in 1991. In 1991, he worked as an assistant at the University of Tokyo’s College of Arts and Sciences, in the Department of Health and Physical Education. In 1996, he worked as an assistant at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in Multi-Disciplinary Sciences, and was promoted to assistant professor in 1999. In 2003, he became an assistant professor at Waseda University’s School of Sport Sciences. He became a professor at Waseda University’s Faculty of Sport Sciences in 2005.

Accomplishments and research

-

2015~,川上筋腱特性開拓プロジェクト, 人間の筋腱特性とその可塑性に関する包括的研究:身体運動能力との関連性からみた効果的なトレーニング方策の確立に向けて(中核研究者課題)

- 2012~2015,身体運動のメカニズムと適応性の解明:骨格筋・腱動態の生体計測によるアプローチ(科研費課題)

- 2009~2011,筋肉痛の発生機序と部位特異性:筋肉痛を抑えながら筋力増強効果を高めるトレーニング(科研費課題)

Reference

- Ema, R., Wakahara, T., Yanaka, T., Kanehisa, H., Kawakami, Y. Unique muscularity in cyclists’ thigh and trunk: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports, 2015. doi: 10.1111/sms.12511.

- Miyamoto, N., Kawakami, Y. No graduated pressure profile in compression stockings still reduces muscle fatigue. Int. J. Sports Med. 36: 220-225, 2015. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390495.

- Sakaguchi, M., Shimizu, N., Yanai, T., Stefanyshyn, D., Kawakami, Y. Hip rotation angle is associated with frontal plane knee joint mechanics during running. Gait & Posture 41: 557-561, 2015. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.12.014

- Shishida, F., Sakaguchi, M., Sato, T., Kawakami, Y. Technical principles of Atemi-waza in the first technique of the Itsutsu-no-kata in Judo: from a viewpoint of Jujitsu-like Atemi-waza. Sport Science Research 12: 121-136, 2015.

- Akagi, R., Iwanuma S., Hashizume, S., Kanehisa, H., Fukunaga, T., Kawakami, Y. Determination of contraction-induced changes in elbow flexor cross-sectional area for evaluating muscle size-strength relationship during contraction. J. Strength Cond. Res. 29: 1741-1747, 2015.

- Wakahara, T., Ema, R., Miyamoto, N., Kawakami. Y. Increase in vastus lateralis aponeurosis width induced by resistance training: implications for a hypertrophic model of pennate muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 115: 309-316, 2015.

- Sugisaki, N., Wakahara, T., Murata, K., Miyamoto, N., Kawakami, Y., Kanehisa, H., Fukunaga, T. Influence of muscle hypertrophy on the moment arm of the triceps brachii muscle. J. Appl. Biomech. 31: 111-116, 2015. doi: 10.1123/jab.2014-0126.

Yukiko Shiki

In 1992, Yukiko Shiki graduated from Waseda University’s School of Human Sciences, with a degree from the Department of Sports Sciences. In 1994, she acquired a Master’s Degree from Waseda University’s Graduate School of Human Sciences. In 2003, she completed a doctoral course at the Graduate School of Human Sciences, acquired a Doctoral Degree (in Human Sciences), and became a part-time lecturer at Waseda University’s School of Letters, Arts and Sciences I. She lectured part-time at Waseda University’s Open Education Center from 2008 to 2013 and at the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences from 2009 to 2013. In 2009, she became an associate professor at Kansai University’s Faculty of Letters-General Department of Humanities, for the Physical Exercise Culture Course. Since 2010, she has been an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Health and Well-being, for the Sport and Wellness Course. She is an adjunct researcher at Waseda University’s Kansei Domain General Research Lab. While enrolled at Waseda University’s Graduate School, she was dispatched to represent Japan for the Olympic International Sports Exchange and International Olympic Academy Session. In the 1990s, she worked as an announcer and commentator for various sports programs on Fuji TV and NHK.

This interview took place at Tokorozawa Campus, home to the Faculty of Human Sciences and the Faculty of Sport Sciences

This interview took place at Tokorozawa Campus, home to the Faculty of Human Sciences and the Faculty of Sport Sciences