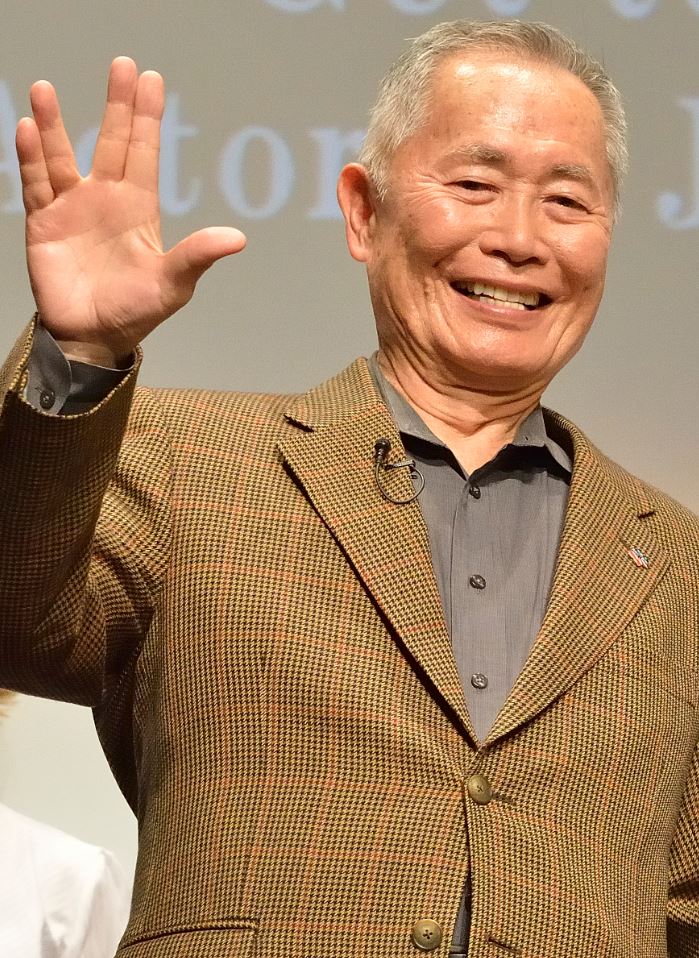

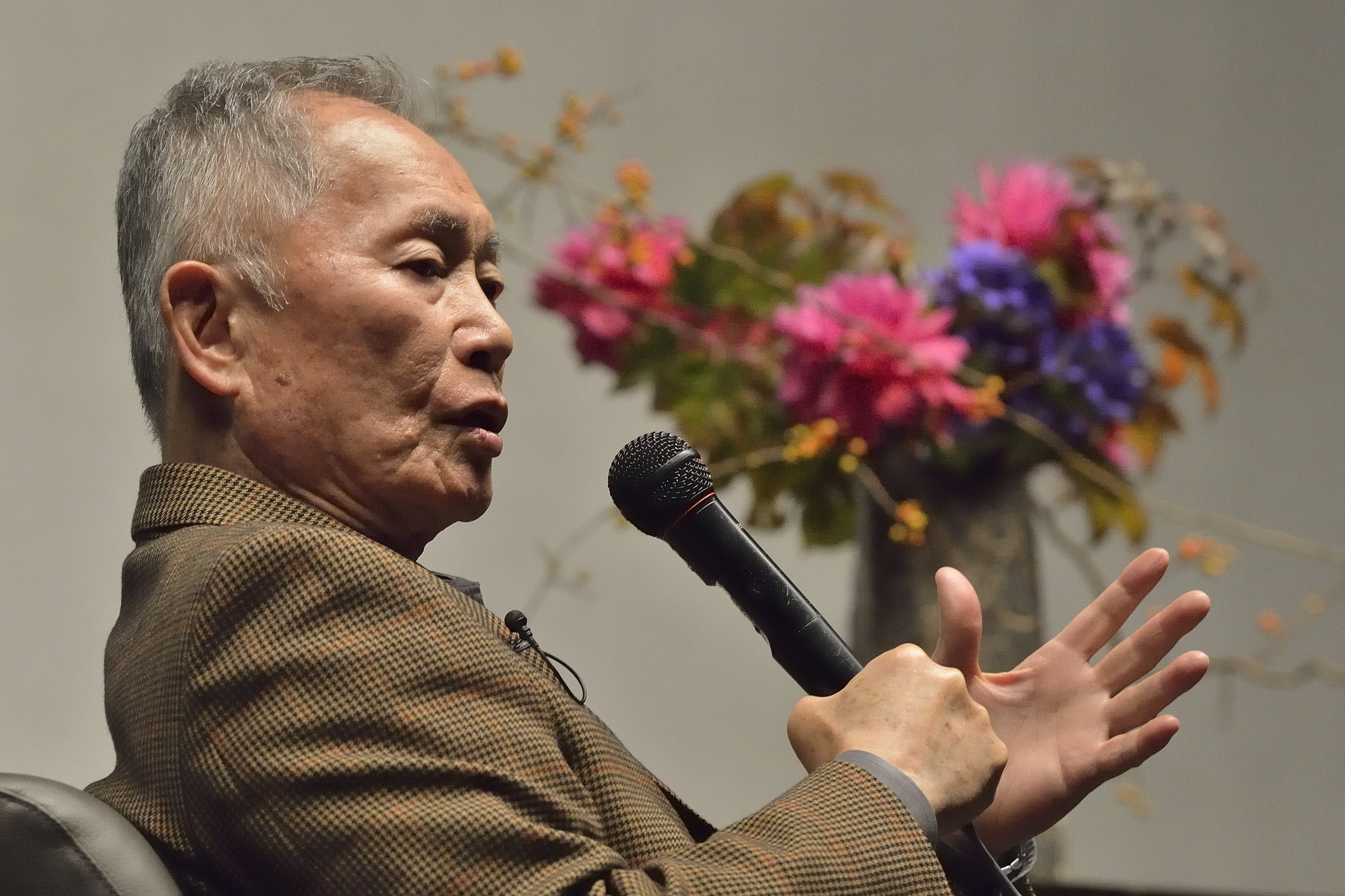

Actor George Takei on being Japanese American and gay

Tue, Nov 14, 2017

Actor George Takei

Best known for his role as Hikaru Sulu in the American Sci-fi TV series “Star Trek,” Actor George Takei spoke at Okuma Auditorium on November 8 about his identity as a gay Japanese American man. This talk was organized by the University’s Intercultural Communication Center (ICC) and the Gender & Sexuality Center (GS Center).

In recent years, Takei’s personal experiences of being imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp during World War II inspired the musical “Allegiance,” which won awards in six categories at the 2016 Broadway World Awards. Furthermore, since coming about his sexuality in 2005, he has been a leading activist in LGBT rights. “It takes initiative on the minority,” Takei answered when asked about how he overcame discrimination during the talk.

Below, he shares his story.

Please share with us about your experience and how you felt while you were unjustly imprisoned.

Indelible memory of terror

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII was the most egregious violation of the Constitution of the United States. I was four years old at the time of the Pearl Harbor bombing, and then immediately, a curfew came down stating that all Japanese Americans had to be home by 8:00PM and stay home until 6:00AM. Soon afterwards, we discovered that our bank accounts have been frozen and straight-jacketed financially. On February 19, 1942, the President of the United States signed an executive order summarily rounding up all Japanese Americans on the West Coast, approximately 120,000 of us. The core value of our justice system simply disappeared.

One fateful morning, my parents got me up very early together with my younger brother and baby sister. They dressed us hurriedly, and my brother and I were told to wait in the living room while they did some packing in the back room. While we were gazing out the front window, we saw two soldiers armed with rifles with shiny bayonets, marching up our driveway. They stomped up the front porch and with their fists, began pounding on the front door. It was a terrifying sound that reverberated through the house. My father opened the door, and literally at gunpoint, we were ordered out of our home. He gave my brother and me small pieces of luggage to carry. We followed him out onto the driveway, waiting for my mother to come out. When she did, she had my baby sister in one arm and a huge duffel bag in another, with tears streaming down her cheeks. That became an indelible memory of terror in my mind. I will never be able to forget that.

Confined in the internment camp

Our family together with the other Japanese American families were rounded up and taken two-thirds of the way across the country to the swamps of Arkansas. There, we were confined in a barbed-wire prison camp. I still remember the barbed-wire fences that confined me, the tall sentry towers with machine guns pointed down at us, and the searchlight that followed me when I made night runs from my barrack to the latrine. To the five-year-old me, I thought it was kind of nice that they’d lit the way for me to pee. I was a child and didn’t understand what was going on.

The extraordinary thing about children is that they are amazingly adaptable. What would have been grotesquely abnormal in normal times became my normality behind those barbed-wire fences. It became normal for me to line up three times a day to eat lousy food in a noisy mess hall. It became routine for me to go with my father and my brother to bathe in a mass shower. And, it became normal for me to go to school in a black tar-paper barrack. I would begin the school day with a pledge of allegiance to the flag. I could see the barbed-wire fence and the sentry tower right outside my schoolhouse window as I recited, “With liberty and justice for all.” I was too innocent to feel the stinging irony in those words.

“’With liberty and justice for all.’ I was too innocent to feel the stinging irony in those words.”

American democracy

When the war ended, the gates of the prison camps were opened. As I became a teenager, I became very curious about my childhood imprisonment. I became a voracious reader of history books and civics books. In these books, I learned about the shining ideals of our democracy but couldn’t connect that with what I knew. The only person I could go to for some discussion was my own father, the man who lost everything in the middle of his life, everything that he worked for. Yet, he was able to explain to me about our American democracy.

My father told me that our democracy is a people’s democracy, having both the potential for greatness as well as mistakes. President Franklin Roosevelt was a great man. During the depth of the Great Depression in the 1930s, because of his political savvy, power, and political initiative-taking, he was able to give people that were lined up starving in soup lines and artists jobs. He brought the nation up from depression. He was a great president but was also a fallible human being with the capacity to horrible mistakes, and he made a horrible mistake. So, my father said our democracy is existentially dependent on people who cherish those ideals and actively participate in the process of democracy. It needs people who understand the positive aspects of democracy to actively engage in it.

Fighting for social justice

One Sunday afternoon, my father drove me downtown to the campaign headquarters of Adlai Stevenson for President. An eloquent speaker, Stevenson was a great governor of the State of Illinois. I was inspired by him. My father and I volunteered at the campaign headquarters, and there I was with other people, passionately dedicated to getting this great man elected president. Then, I understood what it takes, that it’s the people who believe in the best of our democracy and work collectively to make it a reality. It didn’t happen for Governor Stevenson, but my father said in a democracy, you never give up. You keep on keeping on.

I became involved in many political campaigns and active in the civil rights and social justice movements. I did a civil rights musical titled “Fly Blackbird!” and we appeared at many civil rights rallies throughout the Los Angeles area. In the biggest of the rallies, the keynote speaker was Dr. Martin Luther King Junior. He was a soaring speaker. The biggest thrill was being ushered down stairs to Dr. King’s dressing room and introduced to him. This hand that shook his hand didn’t go washed for about three days.

In 2005, you decided to come out as a gay man, and there was a great deal of reaction all around the world. What were you thoughts and feelings leading up to this decision?

Different in more ways

I was slowly getting to realize when I was about 10 that I was different in more ways than my Japanese face. I didn’t want to be different and wanted to be like the other guys because I knew from my childhood that if you were different, you get punished. In addition, the difference that was happening with me was not visible. I wanted to prevent my being punished again. Because of my childhood punishment, I began to pretend that I was like the other boys.

When I started pursuing an acting career, I knew I had to strictly define myself by my pretend self, the straight me. I knew I couldn’t get cast if it was known that I was gay. But by that time, I had discovered gay bars, a bar where I could go with others like me and relax, and not have to be on guard all the time, always that needle-prick anxiety of somehow being betrayed, somebody might have seen me going into a gay bar and verbalized it, or a relationship that went bad and wants to get revenge. Asking myself how I was going to be betrayed or exposed and when that was going to happen was a constant fear.

Criminalized for being yourself

However, an older gay man once told me that we had to be careful even in a gay bar because periodically, gay bars were raided by the police. When the police raided a gay bar, they got everyone out of there, put them in a paddy wagon, drove them to the police station, fingerprinted them, took their pictures, and put their names on a list. That was terrorizing. That could have destroyed their lives. They could have lost their jobs, their career, and maybe their own families could have rejected them. Some people were made feel so worthless that they started doing horrible things to themselves, some even committing suicide. It was a horrible situation.

I was able to then relate that to my childhood imprisonment. Like imprisoned Japanese Americans, here were all these people who were criminalized for what? Just for being themselves. It was so unjust and unfair. I was outraged, but I remained silent because I desperately wanted my career.

“Here were all these people who were criminalized for what? Just for being themselves. It was so unjust and unfair. I was outraged, but I remained silent because I desperately wanted my career.”

Filled with guilt

Then, the AIDS plague hit. Friends would get horribly sick suddenly, drastically lose weight, and pass away. That brought out many people who were willing to sacrifice so much to be active and participate in the process of getting justice. It tore me apart and tortured me to know that I was an activist in all other social justice activities, but still silent on the one issue that was closest and so organic to me. It filled me guilt to see these other guys sacrificing so much and advocating for equality. All through this, I was silent and gave support only through financial contributions to their organizations. I felt my guilt growing heavier and heavier.

The activism of those people who were involved in the gay liberation movement was starting to become visible in results. In 2003, the State of Massachusetts got marriage equality. In California, the people’s representatives, the legislators, both houses, the California Senate and the Assembly, passed the marriage equality bill. It was a landmark event, bookending the nation: on the East Coast, Massachusetts, and on the West Coast, California. That marriage equality bill needed one more signature to become law, which was the signature of our former governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, another actor.

When he campaigned for governor, he said, “I’m from Hollywood, and some of my friends are gays and lesbians.” A number of gays and lesbians in the community voted for him, thinking that by that vote, they might get him to act on his campaign rhetoric. But when the bill landed on his desk, he played to his right wing of the Republican base. He vetoed that bill, and we were angry. By that time, I was together with my husband Brad, back then as a partner. On late night TV news, we saw young people pouring out to Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles, venting publicly against Arnold Schwarzenegger. As raging as we were, we were at home, comfortable. And so, we discussed it. It was about time I make my move. I spoke to the press for the first time as a gay man and blasted Arnold Schwarzenegger’s veto.

Becoming allies of your family members

I joined up with the human rights campaign and a gay advocacy organization in Washington DC, and went on a nationwide speaking tour, trying to communicate the issues of LGBT equality at universities, corporate gatherings, government agencies, and any other opportunities that came by. My husband and I lobbied legislators in Congress, advocating marriage equality. We started gaining many allies. Japanese Americans were visibly different, and it was easy to discriminate against us. However, with the LGBT issue, we are literally members of the family: sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, the flesh and blood. We are like each other. Brad and I pointed out this literal flesh and blood aspect of it, and that some legislators have their own children who might be gay or lesbian. That changed their votes and helped win a lot people, bringing straight people out as allies of their sons and daughters.

Two years ago, the supreme court of the United States of America ruled for marriage equality from coast to coast, border to border. It is we the people that make things happen.

From the left: George Takei, “Allegiance” co-star Elena Wang and lead producer, Lorenzo Thione

Hopeful because this is Waseda

The talk ended with Takei’s words of encouragement for Waseda University, students, faculty and staff. “Waseda University produces leaders, and I am very hopeful that because of this evening and this kind of discussion, things will start happening in Japan as it did in the United Sates. I am hopeful because this is Waseda, a place where leaders come from, a place where students from all over the world come to study. In three years, Japan will be the center vocal point of global attention. The best athletes will be gathering here, and I hope that we have the best thinking going for Japan, to be a proud member of the global community has marriage equality because of your work. So in advance, I thank all of you for what you will be doing.”

In the second part of the event, fellow “Allegiance” cast member Elena Wang sang “Higher” from the musical. SEIREN, Waseda’s official musical circle, then performed “It Gets Better,” a song for the It Gets Better Project, a campaign launched in an effort to prevent suicide among young LGBT people by conveying the message that their suffering is only temporary and that their lives will improve.

*This article has been edited for clarity and length.