Tying Traditions Together Through Mizuhiki at Waseda University

Wed, Dec 24, 2025-

Tags

On Tuesday, November 25th, around forty participants gathered in the Okuma Garden Hall of Waseda University for a workshop dedicated to the traditional Japanese art of mizuhiki. The event was hosted by Waseda University’s ICC (Intercultural Communication Center), an organization committed to connecting students with diverse backgrounds and the wider community through interactive sessions. Through hands-on instruction, attendees explored the craftmanship and symbolism behind mizuhiki and learned how to tie the characteristic knots all while sharing New Year’s traditions across different countries.

The Origin of Mizuhiki

Mizuhiki (水引) are decorative cords made from tightly twisted washi paper, and its name comes from the fact that water-based glue is used to harden it. The cords are often found wrapped around congratulatory envelopes and ceremonial gifts, tied into intricate knots that express good wishes and positive intentions. Historically, the custom of tying mizuhiki dates back to the Asuka period (around 583 CE-710 CE), originally introduced as a form of ornate string decoration used for offerings to the imperial court and the emperor. However, during the Muromachi period (around 1336 CE-1573 CE), it began to be used for gifts in samurai culture. By the Edo period (around 1603 CE-1867 CE), it became more accessible to the public, which led to this gift-giving culture being handed down to the present day.

The Symbolism Behind Mizuhiki

Today, mizuhiki remains deeply connected to major life events such as weddings, births, graduations, and the arrival of the New Year. When wrapping a gift in Japan, the choice of knot, color, number of cords, and washi papers are chosen intentionally to deliver a message of goodwill and, most importantly, symbolize hospitality, sincerity, and the bond between giver and receiver. The colors red and white or gold and silver are common combinations used for happy celebratory occasions, as they mean joyful beginnings and prestige. On the other hand, double silver or black and white are used for somber occasions such as funerals. Apart from the common colors mentioned above, colors such as green, purple, and pink are also used for specific events. However, there is a rule of “left up, right down” when tying mizuhiki, in which the left side is considered more noble than the right. Accordingly, when using cords of different colors, the more noble color is placed on the left. White is regarded as the most noble color, so it is placed on the left whenever it is used; if white is not included, a color closer to white, such as silver, is placed on the left.

The shapes of the knots also hold a specific meaning. A widely used design is the Awaji or Awabi knot, symbolizing enduring connections and lasting bonds, making it popular for weddings and other once-in-a-lifetime milestones. Another is the Ume-Musubi, shaped like a plum blossom, which evokes resilience and hope, as plum trees are the first to bloom in late winter. Additionally, odd numbers such as three, five, or seven cords are traditionally favored because they cannot be split evenly, representing harmony and good fortune that remain unbroken. For example, a single knot is commonly used for friends, three cords are given to those who have helped you, like a teacher or mentor, and five cords are for those you deeply respect, such as parents or superiors. Mizuhiki, therefore, serves as an important visual language in the gift-giving culture of Japan.

About the Event

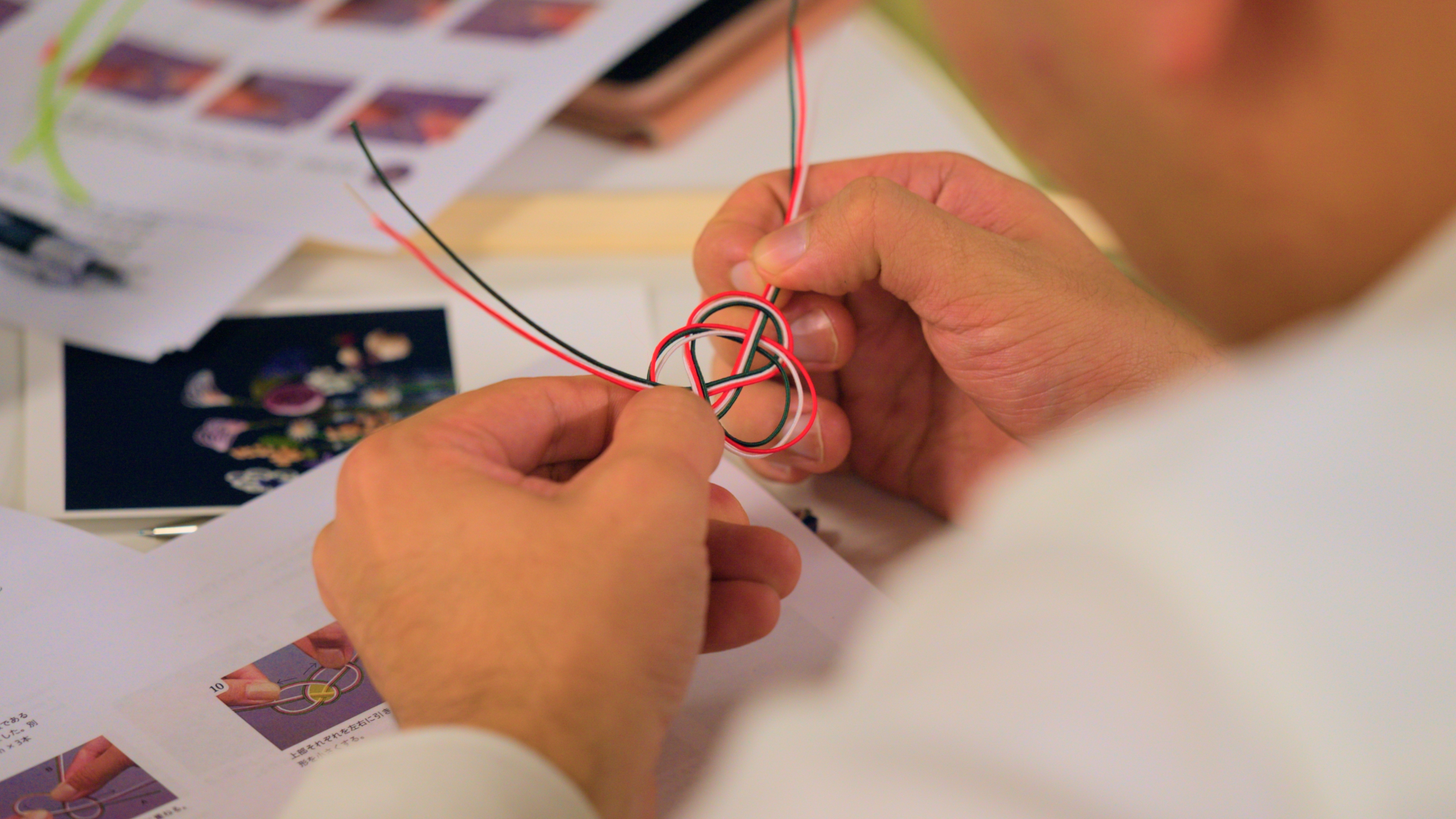

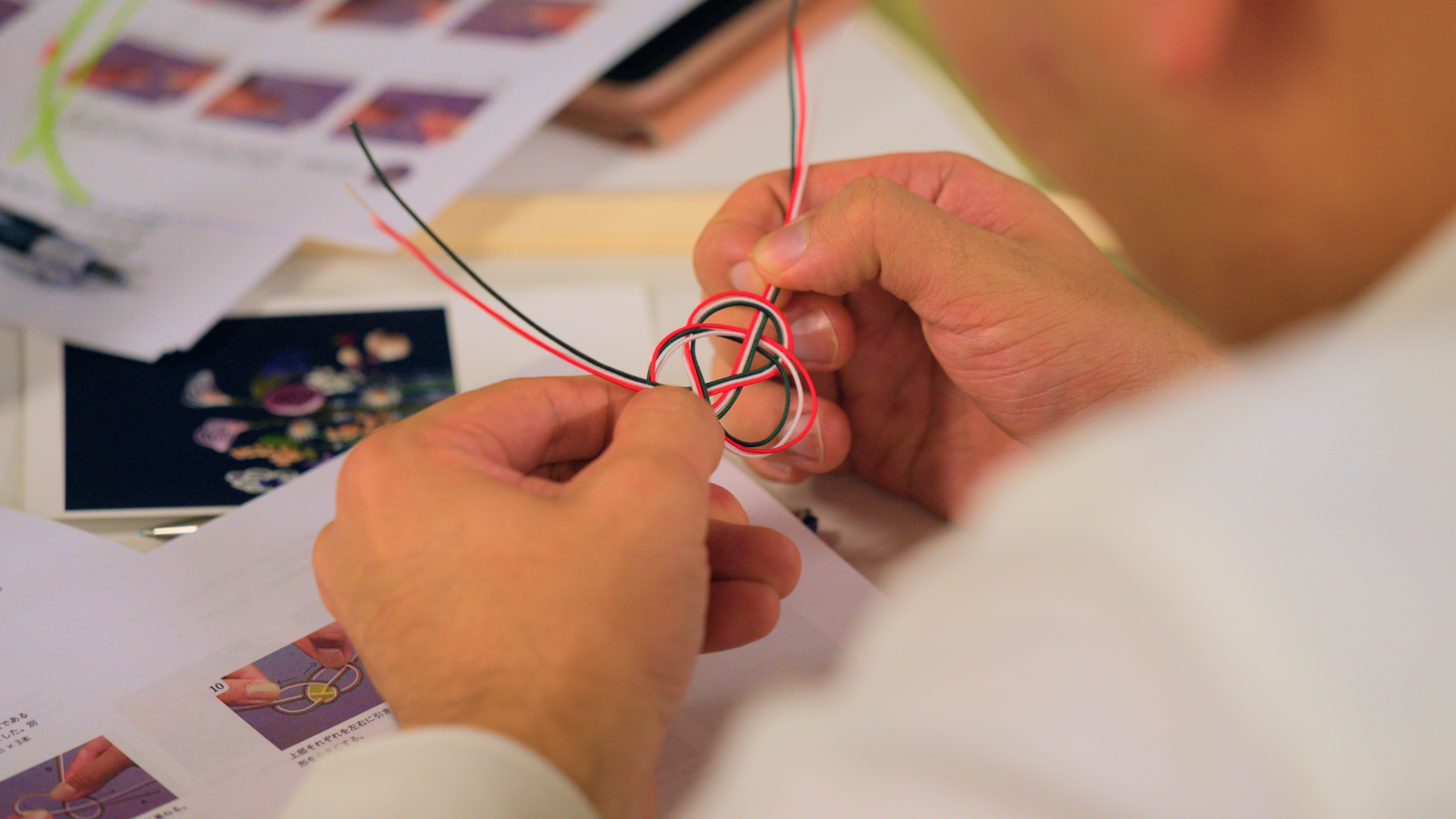

Anna Tanaka, a contemporary mizuhiki artist, served as the guest instructor for the workshop. Inspired by traditional knots, she designs pieces suited to modern lifestyles and frequently collaborates with the public through workshops, exhibitions, and her brand “hare” since 2017. The theme of this ICC workshop centered on New Year (Oshōgatsu) traditions, one of Japan’s most significant celebrations. Participants learned about New Year’s celebratory chopsticks, which are wrapped in decorative sleeves tied with mizuhiki. Creating these chopsticks sets, with the hope that they bring good fortune and protection for the year ahead, served as the main hands-on activity of the event. Under Tanaka’s guidance, participants learned about the materials and how to properly handle mizuhiki cords, such as adjusting tension and shaping curves. With this foundation, participants practiced creating an Awabi knot with one cord. The challenge increased when creating a free-standing plum blossom knot, which requires much more attention as it uses three cords. The final task was attaching the plum blossom to a chopstick sleeve using a makoto-musubi (true knot), which each attendee could bring home.

Mizuhiki Workshop Experience

Despite the concentration required, the atmosphere remained lively and friendly. The ICC staff placed participants into small and mixed cultural groups, which encouraged conversation and collaboration. When someone struggled to hold a knot in place, others offered solutions and supported each other, which was celebrated with laughter. Cultural exchange became a central part of the experience, as attendees shared how New Year is celebrated in their home countries, from festive foods to customs and traditional beliefs. This fostered a social atmosphere where participants not only learned about Japanese culture but also shared New Year traditions from around the world.

For international students, the workshop provided a meaningful way to engage with Japanese tradition beyond the classroom. For Japanese students, practicing familiar customs and explaining to peers offered a fresh perspective and an appreciation for their cultural heritage. True to ICC’s mission, the workshop fostered genuine communication and bonding through shared activity. The event also highlighted the importance of preserving traditional customs. As mass-produced items increasingly define modern consumer culture, the artisanal practice of crafting mizuhiki risks fading. However, workshops like this play an active role in preserving the knowledge and skills and pass them hand to hand, which reminds participants that even small objects carry history and values meant to last.

As the workshop came to an end, participants admired their complete chopstick sets, each designed with a unique style, technique, and color combination. Yet every piece conveyed the same heartfelt message: an appreciation for the elegance of mizuhiki and the enduring traditions it represents. Leaving the Garden Hall with their handmade decorations, participants carried not only a beautiful New Year ornament but also a tangible memory of creating mizuhiki. This workshop demonstrated how an intricate artistic practice can reveal a much larger story of culture, community, and continuity, values that Waseda University and ICC proudly strive to uphold.

This article was written by the following Student Contributor:

San Paing (Emily)

School of International Liberal Studies

- Links