My Encounter with Haruki Murakami, and Taiwan’s

2022.01.27

- Lai Ming-chu

To accompany the opening of the Haruki Murakami Library, we are publishing a series of essays titled Encountering the Literature of Haruki Murakami. This series will provide a forum for people who have been involved in a variety of ways with Murakami’s literature to talk about their “encounters” with his writing, and what “connections” they feel to it.

Taiwanese Murakami translator Lai Ming-chu has sent us a jewel of an essay just in time for Christmas Eve. I met Ms. Lai for the first time at the International Conference of Eastern Studies (Kokusai Tōhō Gakusha Kaigi) a few years ago, but the instant feeling of closeness that sprang up between us made it feel more like I was meeting an old friend. We’ve kept in touch ever since, calling each other to talk about Murakami’s literature or about translation, and whenever we do, we always lose track of time entirely, our conversations lasting for hours—truly, it’s an amazing connection we’ve ended up sharing.

According to my research, Lai Ming-chu was the first person outside Japan to have translated Murakami’s literature, introducing him to foreign readers as early as 1985. Murakami was not very well known in the Sinosphere at that point, and Ms. Lai’s translation became famous not only in Taiwan, but also on the Mainland, where it was carried in literary journals and the like; indeed, it was via her translation that Chinese readers first encountered the literature of Haruki Murakami at all.

So now, without further ado, let’s hear from Ms. Lai about her own encounter with Murakami in the 1980s!

And, as the original title of Hear the Wind Sing puts it, Happy Birthday and White Christmas.

Quan Hui (Editorial Director, Waseda International House of Literature)

My Encounter with Haruki Murakami, and Taiwan’s

Lai Ming-chu

I first saw the name “Haruki Murakami” in a Japanese magazine, after having returned to Taiwan from Japan. While in Japan, I’d read Almost Transparent Blue by Ryū Murakami, who’d won the Akutagawa Prize at such a young age, so when I saw Haruki’s name, I thought, how interesting—another Murakami! And so, I ended up remembering the name of this author I’d never heard of before.

But this turned out to be only the first of many times I’d encounter his name, as he kept popping up in various magazines I was reading. My curiosity piqued, I looked through the last three months of the magazines that the designers at my company subscribed to and found that his name kept popping up—more than a dozen times—in weeklies and monthlies alike, and especially in the magazines aimed at women and at people working in advertising. Around the time A Wild Sheep Chase won the Noma Literary Newcomer’s Prize in November of 1982, the book had been introduced to readers many times over in reviews appearing in a variety of Japanese publications. Reading these reviews, I learned that his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, had won the Gunzō Prize for New Writers, and that his novel Pinball, 1973 had become very popular among young readers.

I was working as a copywriter for an advertising agency in Taipei at the time, and I visited Eikan Bookstore, a Japanese-language bookstore on Zhongshan North Road, to see if they had any of these books. As it turned out, they had all three parts of this early trilogy on their shelf: Hear the Wind Sing; Pinball, 1973; and A Wild Sheep Chase. Enchanted by the colorful, mysterious art by Maki Sasaki on their covers, I bought all three, and thus began my reading of the novels of Haruki Murakami.

I remember being particularly taken by the sentence that starts Hear the Wind Sing.

完璧な文章などといったものは存在しない。完璧な絶望が存在しないようにね。

“There’s no such thing as a perfect piece of writing. Just as there’s no such thing as a perfect despair.” (Ted Goossen, trans.; from Wind/Pinball [New York: Vintage International, 2015])

A “perfect despair”? The word usually used to modify “despair” would be “total,” wouldn’t it? Yet the phrase “perfect despair” left a surprisingly deep impression. This was evidence of the author’s unique sensibility, surely. Haruki Murakami’s choice of words was designed to strike readers as unusual, surprising. I tried my hand at translating the sentence into Chinese.

所謂完美的文章並不存在。就像完美的絕望不存在一樣噢

In Chinese, the phrase “perfect despair” —完美的絕望—strikes the reader as slightly off, as it would be more usual to use the phrase “total despair”— 完全的絶望. But “total despair” is too usual, sounding completely banal and lacking any sense of surprise, and the wordplay and fun of the original is lost. When I ended up translating the whole novel, I went back and forth about this quite a lot—“perfect” despair, or “total”? As I became more familiar with his unique individuality and style, though, it became clear that Haruki Murakami was a perfectionist.

In Japanese, the sentence “Just as there’s no such thing as a perfect despair” ends with the particle “né.” “Né” is an extremely Japanese way to end a sentence; we have very few such endings in Chinese. And so, when it comes time to translate it, I am presented with a conundrum: should I leave it, or leave it out? These sorts of ending are used in Japanese as ways of respecting the feelings of others, and they create a sense of closeness between speaker and listener. I felt that I must recreate this very Japanese sense of solicitude in my translation, and so in some instances, I left the “né” ending in, transforming it into the Chinese “噢.”

There are some other scenes in this early trilogy that left an impression on me.

「あと25万年で太陽は爆発するよ。パチン……OFFさ。25万年。たいした時間じゃないがね。」

風が彼に向ってそう囁いた。

……

「太陽はどうしたんだ、一体?」

「年老いたんだ。死にかけてる。私にも君にもどうしようもないさ。」

「何故急に……?」

「急にじゃないよ。君が井戸を抜ける間に約 15 億年という歳月が流れた。君たちの諺にあるように、光陰矢の如しさ。君の抜けてきた井戸は時の歪みに沿って掘られているんだ。つまり我々は時の間を彷徨っているわけさ。宇宙の創生から死までをね。だから我々には生もなければ死もない。風だ。」

“In another 250,000 years the sun will explode,” a voice whispers. “Click…OFF! 250,000 years. Not so far away, you know.”

It is the voice of the wind.

[…]

“But what has happened to the sun?”

“It got old. It’s dying. There’s nothing either of us can do about it.”

“But it’s so sudden…”

“Sudden? Hardly. One and half billion years passed while you were down the well. As you earthlings say, time flies. The tunnels you passed through run along a time warp—that’s why we dug them as we did. They allow us to wander across time. From the creation of the universe to its final demise. We exist in a realm outside life and death. We are the wind.” (Hear the Wind Speak, Ted Goossen, trans.)

Look at the complete control he exercises here, moving from the realistic to the unreal so freely, the scale of time and space spreading out into infinity, able to speak of life and death so directly—it’s fascinating.

やあ、元気かい?こちらはラジオN・E・B、テレフォン・リクエスト。また土曜日の夜がやってきた。……今日はレコードをかける前に、君たちからもらった一通の手紙を紹介する。

……

僕は・君たちが・好きだ。

あと10年も経って、この番組や僕のかけたレコードや、そして僕のことをまだ覚えていてくれたら、僕のいま言ったことも思い出してくれ。

Hey, all you out there. How’re you feeling tonight? It’s Saturday evening again, time for your Greatest Hits Request Show, right here on NEB Radio. […] I’m gonna shake things up a little tonight, read you a letter I just received from one of our listeners before we start the music.

[…]

I love all you kids out there!

If you remember anything about this program in ten years—the songs I played for you, perhaps, or maybe even yours truly—then please remember that. (Hear the Wind Speak, Ted Goossen, trans.)

Murakami includes a sketch he made of the NEB Radio t-shirt in Hear the Wind Sing. Now, forty years later, he’s the DJ for his own show called Murakami Radio where he can play whatever records he chooses, listening to them with his readers, talking with them, even designing t-shirts inspired by his novels that readers can buy from UNIQLO.

In Pinball, 1973, there are two nameless twin girls who go by 208 and 209, the numbers on the T-shirts they received at the opening of a supermarket as the 208th and 209th customers.

A Wild Sheep Chase unfolds as a series of mysteries: Dolphin Hotel, Junitaki Village, the Ainu youth, the Sheep Professor, the Sheep Man, the history Hokkaidō’s modern settlers, the Manchurian War….

I returned to Eikan Bookstore filled with the desire to read whatever else I could find by Murakami. Besides the trilogy, I ended up buying everything they had that was either by or about him: the short story collections A Perfect Day for Kangaroos and A Slow Boat to China, the photobook Pictures of Waves, Tales of Waves that he co-created with Kōichi Inakoshi, the essay collection Happy Ending at the Elephant Factory that he cowrote with Mizumaru Anzai, and literary critic Saburō Kawamoto’s book The Sensitivity of the City, which includes in-depth analyses of Murakami’s writing. I bought them all and read them, one after the other.

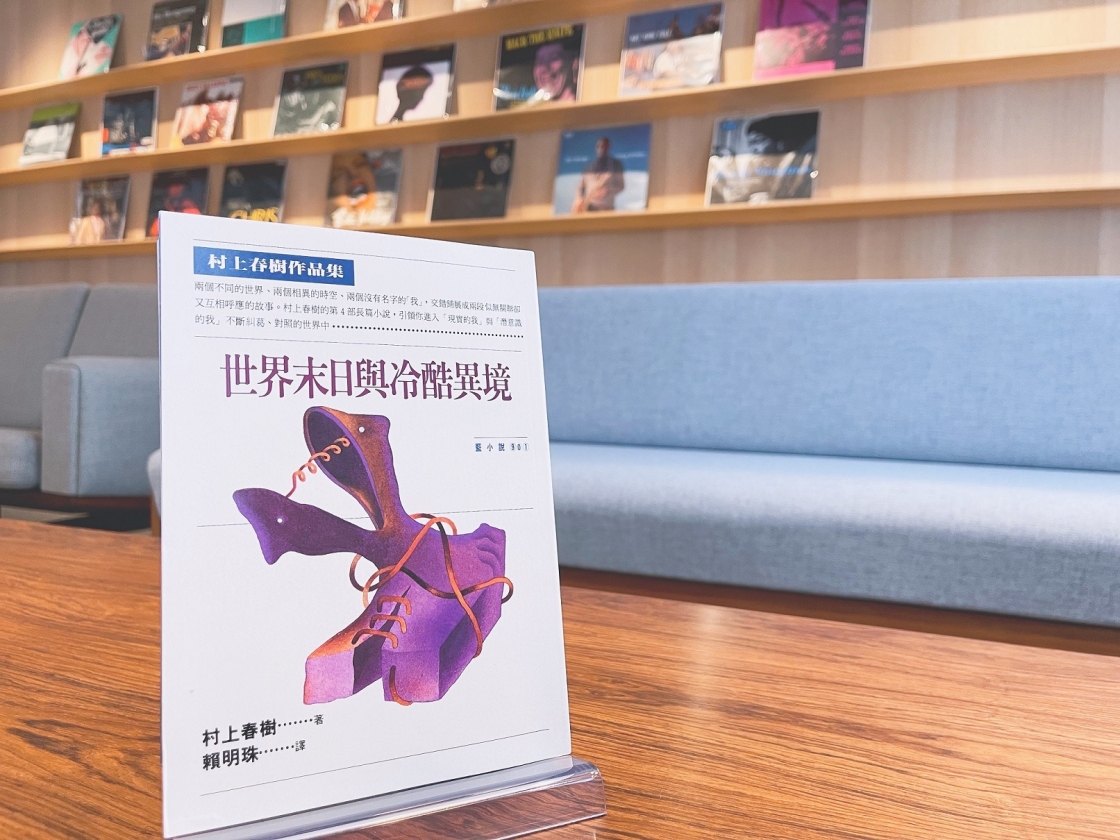

Thinking that I wanted to introduce Taiwanese readers to this new author’s wonderful works, I talked to Zhou Haozheng, my former colleague at the ad agency, Qiao Lian, who had moved on to become the editor-in-chief at New Book Review Monthly. “Translate it and show it to me, and if it’s as wonderful as you say, we’ll run it,” he said. In the end, my first Murakami translations came out in a special feature called “The World of Haruki Murakami” in New Book Review Monthly, No. 23 (August 1985).

I translated three essays from Saburō Kawamoto’s The Sensitivity of the City (“Authors in the City,” “The ‘No Generation’ of the 1980s,” and “The World of Haruki Murakami”), introduced Murakami’s style to readers, and then translated three short Murakami pieces: “Streets of Illusion,” “Supermarket Lifestyles of the 1980s,” (from Pictures of Waves, Tales of Waves) and “Sunset in the Mirror” (from Happy Ending at the Elephant Factory); the special feature ran ten pages in total. It was through the “The World of Haruki Murakami” special feature in New Book Review Monthly that Taiwanese readers first encountered the name “Haruki Murakami.” (Later, I learned that this was the first time his work was introduced to any audience outside Japan at all).

However, New Book Review Monthly ended its run with its subsequent issue (No. 24), and Zhou went on to become the editor-in-chief at China Times. When I asked if Murakami’s works might be published there, I was told that they would reserve judgment until they saw more works in translation.

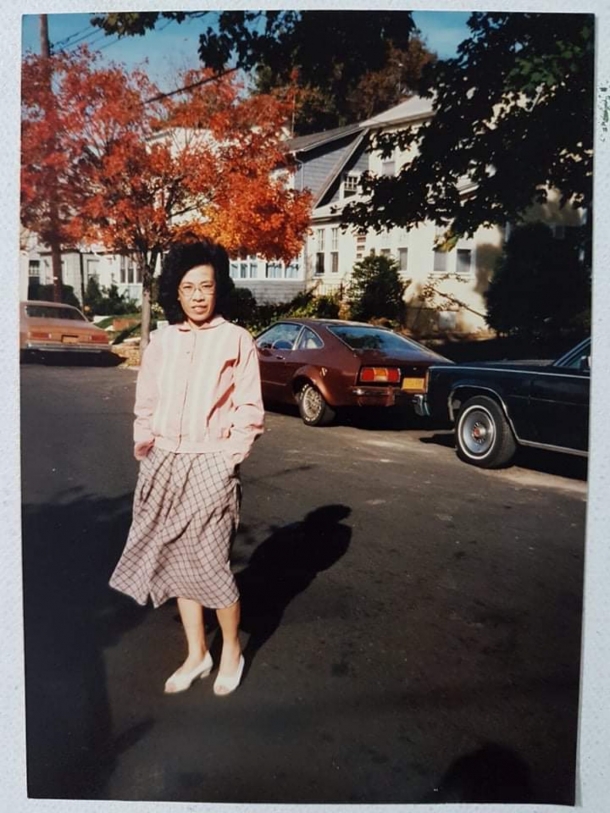

It was then that I quit my job and travelled to the USA to translate more of Murakami’s novels. I visited my older brother and a friend, and during my travels, I translated Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973 and sent them to Zhou at China Times for review.

“The World of Haruki Murakami,” New Book Review Monthly, No. 23 (August 1985)

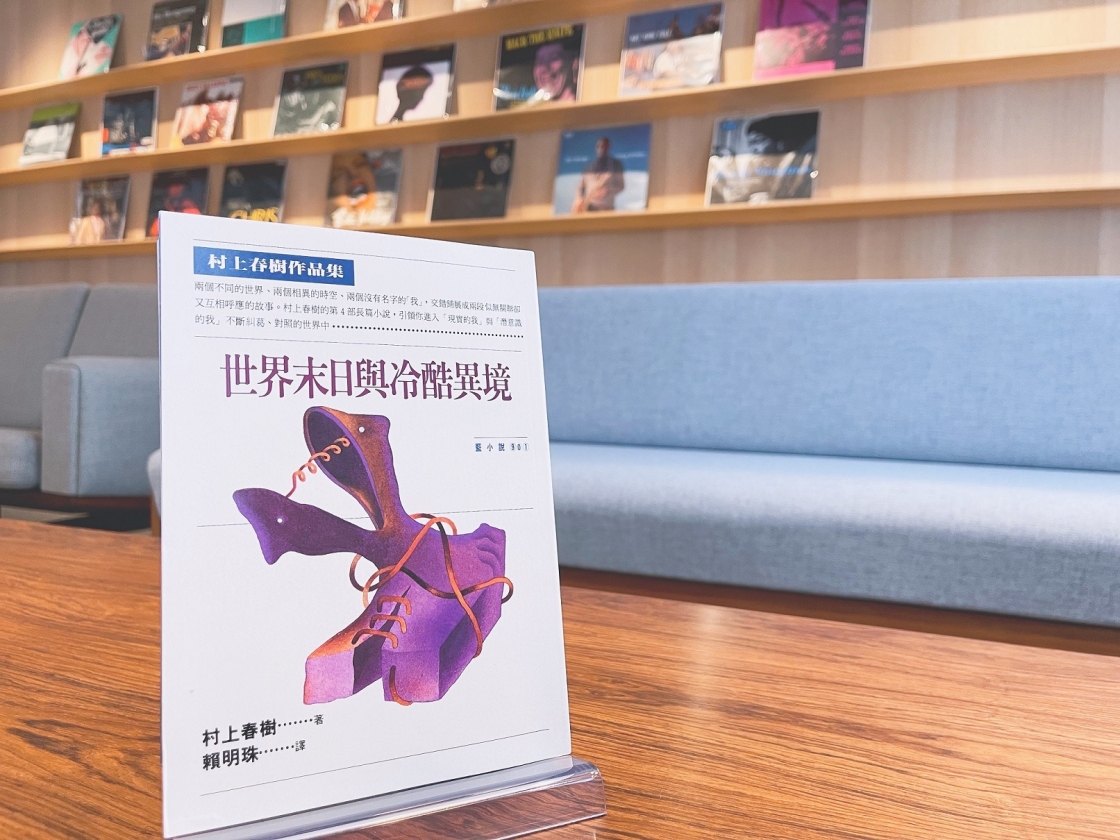

Later, when I was living in New York, I went to the Kinokuniya bookstore on Sixth Avenue and came across Murakami’s new novel, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. As I started to read it, I found that it was a novel written in a new style, one that told two intertwining stories at once. Excited, I read through the book as if watching a movie, impressed by the freshness of its images: the Elevator, the golden Beasts, the Library, the Shadows, the Wall, the Map of the End of the World¬—. Summer had passed in New York, and a beautiful autumn had arrived; the sides of the roads were blanketed in golden leaves. As the temperature got lower and lower, the increasingly severe cold reminded me of winter in Tokyo, and it struck me as so strange to be reading Hard-Boiled Wonderland… in a foreign country like this, but also so oddly perfect—in fact, it struck me that to be able to read about both the End of the World and the Hard-boiled Wonderland in New York was an unbelievably perfect coming together of events.

Along with Hard-Boiled Wonderland…, I’d bought Happy Jack: Heart of the Rat—A Haruki Murakami Studies Reader, which I found fascinating, as it included critical and personal essays by contributors from a wide variety of fields. I was especially impressed by Takashi Masaki’s essay, “A World of Japanese Spirit in Western Clothing,” with which I wholeheartedly agreed. I felt it expressed exactly how I felt as I translated Murakami’s first two books.

I decided then that I wanted to translate A Wild Sheep Chase and Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. I returned to Taipei and inquired to Zhou about the publisher’s intentions.

Managing Editor Chen Yu-Hang, himself an author, explained it this way, “I like Murakami’s style too—I find it so refreshing. But we want to leave his debut piece, Hear the Wind Sing, for later, and publish Pinball, 1973 first. We also think that it’s easier to hook new readers with short stories, so we’d like you to translate a collection of short stories to put out as well.”

When I translated the collection A Perfect Day for Kangaroos, the response was, “The content is very interesting, but the title is too fairytale-like and invites misunderstanding. I think we should borrow the title of another story: “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning.” But that’s too long, so let’s shorten it to On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl [in Chinese: 遇見100%的女孩].” It turned out to be a great title. Many readers apparently ended up buying one copy for themselves and one copy as a gift for their lover, and it has turned out to be a longtime bestseller.

On June 15, 1986, my translation of Pinball, 1973 came out [in Chinese: 1973年的彈珠玩具], which was followed half a year later by the collection On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl [in Chinese: 遇見100%的女孩]. My translation of Hear the Wind Sing was finally published a year and nine months later, on April 1, 1988.

The author, Lai Ming-chu, during her stay in New York

Wanting to introduce the wonderfulness of Haruki Murakami to more readers, I contributed a profile of Murakami to a feature on “The Literary Standard-Bearers of 1980s Japan” for the first year anniversary issue of the magazine Japan Digest in January of 1987, as well as translating the story “A Slow Boat to China” for the issue.

That same year, on September 10, Norwegian Wood was published in Japan.

The cover claimed that it was “The Most Intense 100% Love Story of Today,” and it quickly became a bestseller.

Japan Digest caught wind of this development and immediately put together a team of five translators—劉惠禎, 黃琪玟, 傅伯寧, 黃翠娥, and 黃鈞浩—to produce a translation for their affiliated publishing company, 故郷Publishing House. It came out on February 25, 1989, as 挪威的森林.

Most Taiwanese readers say that the first Murakami novel they ever read was this translation of Norwegian Wood.

Readers encounter Murakami’s works and become taken with the freshness of his style and the freedom of invention in his stories. There’s also a feeling of closeness, arising from his ability to use simple words to express deep meaning in lively ways—this is stimulating to the reader, and inspiring.

“I might be able to write something myself.”

“I want to write just as I think.”

Not a few readers of Murakami’s literature end up feeling encouraged to write their own stories, draw their own pictures, compose their own songs.

Nothing brings me more pleasure, nor makes me happier, than to be a longtime reader and translator of Murakami’s works.

(Translated by One Transliteracy, LLC)

January 28, 2022

Profile

Lai Ming-chu was born in Miaoli County, Taiwan. In 1969, she graduated from the Agricultural Economics Department at National Chung Hsing University, and then, after working there as an adjunct researcher, went to Japan to study in the Horticultural Science Department at Chiba University in 1975. After returning to Taiwan in 1978, she worked as a copywriter in the advertising world. In 1985, she began translating works by Haruki Murakami, and her Murakami translations now number over forty works. She has also introduced many other works of Japanese literature to Chinese readers, starting with A Portrait of Shunkin by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki.

One TransLiteracy, LLC, is a boutique translation and cultural consultation agency founded by Miyabi “Abbie” Yamamoto, Ph.D. We are a team of highly educated native or native-level bilingual and bicultural experts who provide meticulous translations with linguistic acuity, hone texts for precision and elegance, and provide concise explanations of cross-cultural exchange. The founder, Abbie, grew up in Tsukuba, Japan and received her Ph.D. in Japanese and Korean literatures at the University of California, Berkeley. She is passionate about promoting cross-cultural exchange and everyday practices of intentional inclusion.

*This article was made possible through the support of the Waseda International House of Literature and Top Global University Project in collaboration with Waseda University’s Global Japanese Studies.

Related

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Rebecca Brown

2025.12.02

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Camilla Grudova

2025.10.20

-

Memories of Things That Never Happened to You

2022.12.12

- Hideo Furukawa

-

Historical Consciousness and “Boomerang” Thoughts in the Works of Haruki Murakami

2022.05.08

- Tetsurō Koyama

-

Useful Landscape

2022.03.28

- Ryō Mizuhara

-

My Personal History with the Literature of Haruki Murakami

2022.02.25

- Shōzō Fujii