On Meeting the 100% Perfect Haruki Murakami

2021.11.29

- Ye Hui

In conjunction with the opening of The Haruki Murakami Library at Waseda University, a series of essays was commissioned entitled Encountering Haruki Murakami. These essays will allow people involved in various ways with Murakami to talk about their encounters and connections with his works and his world.

Quan Hui (Editorial Director, Waseda International House of Literature)

On Meeting the 100% Perfect Haruki Murakami

葉 蕙/ Ye Hui

1. Murakami, My 100% Perfect Author

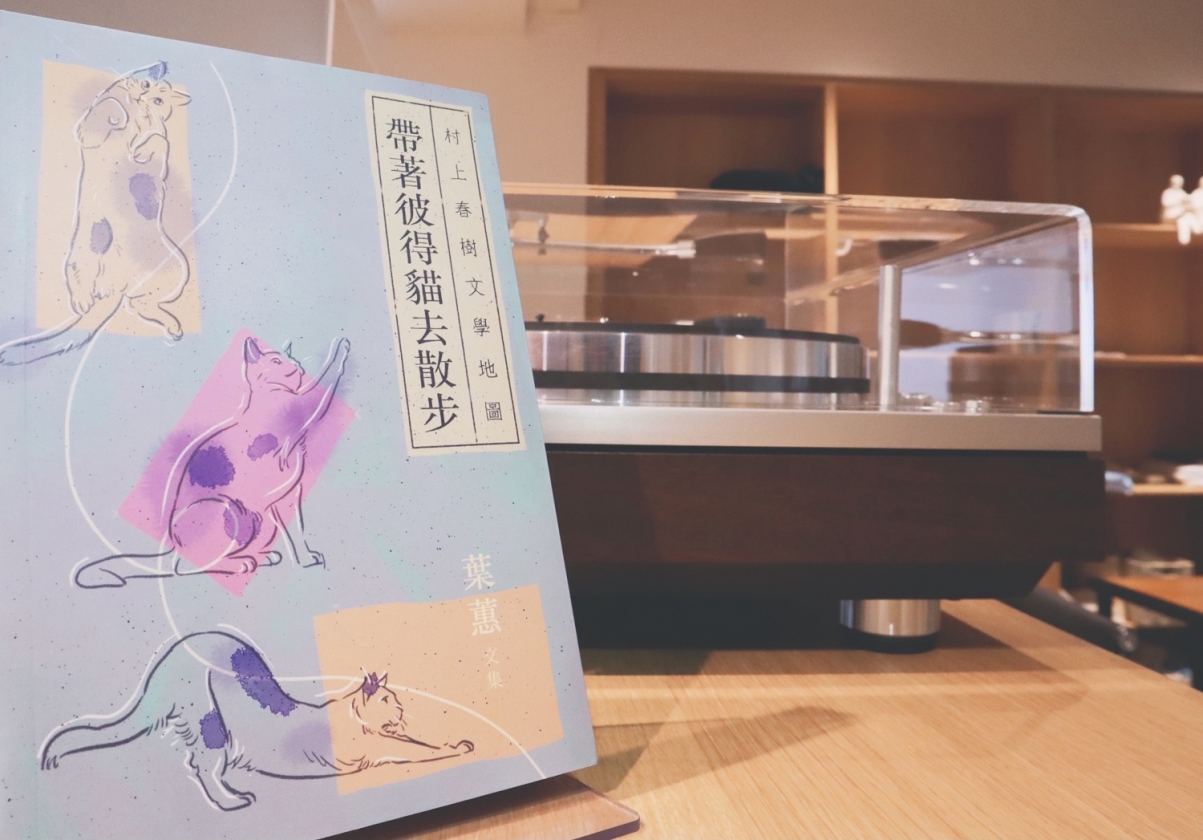

My engagement with Haruki Murakami began around 1990. I was living in Hong Kong at the time, and the people at the former Boyi Publishing Group (which closed its doors in2008) asked if I would be interested in translating one of his works. Most recently, I published an anthology of Murakami-related pieces called Taking a Walk with Peter Cat: A Map of Haruki Murakami’s Literary World. It is split into four parts: essays, interviews, translations, and there are also photographs of important Murakami-related things, including a tour of locations that have served as settings for his stories. It is a book that details the journey my heart has been on as I have translated and researched Murakami’s writing for the past thirty years. I wrote it as an homage to a world-class literary figure, of course, but also to a writer who, for me personally, is my 100% Perfect Author.

Murakami’s so-called “postmodern” writing emerged in the Chinese-language literary market as “urban” literature during the Japanese “bubble economy” of the 1980s. The first novel of his to be translated into Chinese was Pinball, 1973 (1986, in Taiwan), but it did not receive much attention at the time. Subsequently, though, a team of five Taiwanese translators published their joint translation of Norwegian Wood in 1989 and touched off an unprecedented Murakami boom. Starting in the beginning of the 1990s, translations of Murakami’s works were put out by publishers in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Beijing, signifying the true beginning of the “Haruki Murakami Phenomenon.”

Murakami’s stories, from the choice of words and sentence construction to the choice of props and cultural mores they portray, display tendencies that differentiate it from traditional Japanese literature. Jazz and classical music, Western art and literature, various kinds of Western alcohol and food—these are the types of things found in the various scenes that make up his narratives, and the lifestyle enjoyed by his characters became a major source of attraction for Chinese-language readers. The most distinctive of these elements is the music that provides his language with its rhythm, a quality that was rare to find in Japanese literature up till that point. I, too, found myself progressively more taken with his distinctive style as I began to translate his work in the 1990s, until I became fully in its thrall.

Murakami enjoys Western music of all sorts, including pop, rock, blues, classical, and so on, but he is most known as a passionate fan of jazz. His novels are littered with descriptions and references to jazz, and the aesthetic sense that emerges in essay collections like the two volumes of Portrait in Jazz and If It Ain’t Got That Swing, It Don’t Mean a Thing captured the hearts of his fans; many of the songs referenced in his novels ended up becoming bestsellers because of it. For example, Aomame, the heroine of 1Q84, listens to Leoš Janáček’s Sinfonietta in the taxi at the beginning of the novel, which lead his compositions to explode in popularity from the Murakami effect. One distinction that may be drawn between Murakami’s writing and traditional Japanese literature is how his language embodies musicality in a way that seems to transcend linguistic expression.

Against the backdrop of the postmodern age, Murakami captured the ardent support of younger readers with his fresh figurative language, his descriptions of his characters’ freewheeling lifestyle, and his inclusion of various signifiers of consumer culture. Within the Chinese-language literary establishment, he became an attractive model to follow, especially among the newest generation of writers. There was much to learn from Murakami’s novels for literature lovers. So many readers found themselves taken by the harmony they found between their literary sensibilities and these novels’ artistic conceptualization and atmosphere.

2. On the Murakami Boom in Malaysia

I am originally from Malaysia, which after a period of British colonization transformed into the multiethnic nation that it is today, giving it a broadminded receptivity to influences from foreign cultures. Further, Malaysia’s Chinese community has always been deeply influenced by the traditional cultures passed along through various Sinophone societies, including those of mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and so on.

Starting in the 1980s, Malaysians, especially young people in the Chinese community, began to be very interested in Japanese pop culture, and a version of the “Harizu” phenomenon —that is, a craze for all things Japanese among Chinese young people— swept the nation. All sorts of Japanese cultural products, including manga, anime, television dramas, J-Pop music, etc., began to arrive one after another. I myself was an international student in Japan during the 1980s, and I found myself solicited by Chinese-language newspapers and magazines to talk about my experience; I ended up writing many articles about Japanese cultural trends, including movies, music, food, and fashion. Thinking back on it now, I was clearly engaged in what Murakami, in one of his novels, famously termed “cultural snow shoveling.”

While the established Chinese media in Malaysia had no particular interest in covering Japanese literature, there were many Murakami fans among them who were drawn to his fresh style and rhetoric. Especially among writers and other cultural figures, there were many avid Murakami readers who developed a newfound interest in Japanese literature more broadly. The Malaysian Chinese-language newspaper Nanyang Business Daily conducted a survey in 1999 to select the “Top 100 Books Loved by the Malaysian Chinese Community,” and among them was Murakami’s Norwegian Wood. It is said that Murakami’s literature becomes a hit first through the marketing effects of mass media. In Malaysia, the Chinese-language newspapers and literary journals certainly play an important role in driving his books to become such hits.

In 2005, Professor Shōzō Fujii, a scholar of Chinese literature teaching at Tokyo University at the time, began a four-year joint research project called “Haruki Murakami and East Asia,” which resulted in a collected volume of articles on the topic. I was one of the members of this research project, and I reported on the reception of Murakami in Malaysia, detailing how the Murakami boom had been touched off in the 1990s with local literary journals like “椰子屋, ”“向日葵,” and “青梳” publishing special issues on him one after the other, thus creating a new population of dedicated Murakami readers. Unfortunately, all of those journals are now either on hiatus or out of business entirely. Malaysia’s multilingual environment makes its literary markets rather unstable, and Chinese-language publishing is a particularly harsh world to try to survive in, which means that without considerable economic resources, it is unlikely for a publishing project to last very long.

Malaysia differs, of course, both politically and socially from other places in East Asia like China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, and so its version of the “Murakami phenomenon” was also distinctive.

Looking back over the various cultural phenomena that have gripped the Malaysian Chinese community, one sees that while the 1970s were obsessed with the romance novels of the Taiwanese writer Chiung Yao, during the 1980s, it was Hong Kong television dramas that reigned supreme. After that, the aforementioned Harizu phenomenon arose, and Japanese manga and English-dubbed anime flooded the country. The Murakami boom also began at the start of the 1990s, but even though the Harizu and Murakami phenomena occurred at roughly the same time, there was not such a deep connection between them. This is because there simply is not that much Japanese cultural material to be found in Murakami’s fiction.

There is a popular literary blog in Malaysia called “有人部落” that has become a gathering place for young Chinese writers. It is a forum for club members to share writings they like and to have literary discussions. Naturally, Murakami also became atopic of conversation. In January of 2007, I collaborated with them and published an online quiz called Who Knows the Most About Haruki Murakami?, as well as a “Haruki Murakami Survey.” These events led to my meeting many Murakami fans, and the discovery that almost all Malaysian-Chinese writers and literature-lovers were faithful readers of Murakami’s work, or at least paid attention to his work.

In 2003, the young Malaysian-Chinese writers who ran the “有人部落” blog set up a publishing house called “有人出版社” in Kuala Lumpur. Even now the company valiantly fights to keep running, its main members employed in areas such as advertising, IT, news media, publishing, music, film, finance, and the like while helping to run this publishing house on the side. It has put out 150 titles so far. In the present age, when literature hardly sells at all, this publishing house has nonetheless managed to maintain a considerable amount of popularity.

The postmodern style and descriptions of urban life found in Murakami’s work bring it close to the literary tastes of the new generation of novelists and poets. When one looks at the works published by 有人出版社, one sees the postmodern expressions found in Taiwanese poetry and the style used in Chinese translations of Murakami’s fiction combined. This style shows up in the works of some of the new Malaysian and Singaporean poets, showing the influence Murakami has had on writers in both countries.

Murakami’s novels express the everyday psychological state of the modern city dweller through the novelty of the topics he takes up, the meticulousness of his story structures, and the uniqueness of his literary expressions. His characters and choices of metaphor allow the reader to experience “the reality of living” confronted by people everywhere. Considering this along with the many readers who seem to see Murakami as “someone who guides me psychologically toward self-realization,” one can see that while his literature is certainly read as “foreign,” his fresh style and use of language has had a certain degree of influence on the creative direction and rhetoric employed by Malaysian writers. The writers and readers of the early run of the literary journal “椰子屋” are examples of this, including 荘若, 祝快楽, 孫德俊, 林健文, 陳文貴, and 陳志鴻. But it must be remembered that these Malaysian writers were also influenced by writing coming from the Sinophone world as well as the West, and so in this way should be seen as creating their own distinct archive to draw upon in their work. Further, each author’s personal experiences and lifestyle of course impact their writing, making it irreducible to a simple reflection of Murakami’s style.

Nevertheless, it remains the case that for Malaysian-Chinese writers, especially those born in the 1970s and 80s, Haruki Murakami is a special presence. Especially in terms of the psychological aspects of urban life during a period characterized by a sense of emptiness and loss, the jazz, the literature, the food, the brand-name items, and so on that appear in the urban landscapes of Murakami’s work attracted young people in particular, and there was, for a time, a boom in “life imitating art”-style behavior—we must not forget, however, that these were tastes not necessarily borne directly from each person’s hearts.

As a final note to conclude my analysis, I would like to point out that while Malaysian Murakami readers were influenced at the level of cultural consciousness by his physical descriptions of things and by his musical tastes, this was unrelated to the acceptance of any national or ethnic identity. Further, people who like Japanese literature are interested in different sorts of things than those caught up in the Harizu boom, and because of this, these cannot be discussed as belonging to the same category.

3. Bewitched by Murakami’s Literature

The allure of Murakami’s literature lies in its narrative language and metaphoric expressions. His words are suffused with a therapeutic quality, able to penetrate readers’ subconscious and heal them.

Readers’ tastes are not unitary, but even so, it remains true that Haruki Murakami has left an important mark on the Malaysian literary scene. One could say that there is almost no one among the new generation of popular Malaysian writers who has not read him. Much like the Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai constructed a new cinematic language in the realm of filmmaking, Haruki Murakami forged an avant-garde literary language from the postmodern style of his time.

In the post-COVID era, “loss” and “emptiness” have become affective codes for a common, universal feeling among people living today. Speaking broadly, one could say that Malaysia is constantly creating a distinctive culture out of pop culture influences from Japan and the West layered upon a foundation of traditional culture received from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Murakami’s work will surely be read well into the future among young people who are becoming increasingly individualistic amid the rapidly shifting tides of the postmodern age.

October 10, 2021

Profile

Ye Hui is a Malaysian-born translator. Approximately three hundred of her translations have been released through publishers in Hong Kong. Starting in the early 1990s, one of these Hong Kong publishers asked her to translate works by Haruki Murakami, which led to her translating Norwegian Wood, A Wild Sheep Chase, and Dance, Dance, Dance.These days, she continues her translation work while also working as a professor of Japanese. She is the author of Taking a Walk with Peter Cat: A Map of Haruki Murakami’s Literary World (2020).

*This article was made possible through the support of the Waseda International House of Literature and Top Global University Project in collaboration with Waseda University’s Global Japanese Studies.

Related

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Rebecca Brown

2025.12.02

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Camilla Grudova

2025.10.20

-

Memories of Things That Never Happened to You

2022.12.12

- Hideo Furukawa

-

Historical Consciousness and “Boomerang” Thoughts in the Works of Haruki Murakami

2022.05.08

- Tetsurō Koyama

-

Useful Landscape

2022.03.28

- Ryō Mizuhara

-

My Personal History with the Literature of Haruki Murakami

2022.02.25

- Shōzō Fujii