Third Time’s a Charm : My Encounter with the Literature of Haruki Murakami

2022.01.11

- Shi Xiaowei

To accompany the opening of the Haruki Murakami Library, we are publishing a series of essays titled Encountering the Literature of Haruki Murakami. This series will provide a forum for people who have been involved in a variety of ways with Murakami’s literature to talk about their “encounters” with his writing, and what “connections” they feel to it.

This third essay is by Professor Shi Xiaowei. I first met Professor Shi at The East Asian Cultural Sphere and the Literature of Haruki Murakami conference held at Waseda University in the winter of 2013. When I found out that Professor Shi was attending the conference, I contacted him online to arrange a meeting and quickly received a kind acceptance of my invitation. Not only that, but he inquired as to whether I’d acquired the Chinese translation of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage yet, offering to bring me a copy as a present if I hadn’t! I was so moved by his consideration. I could offer more anecdotes illustrating his knack for encouraging and mentoring young thinkers, but I think it more appropriate to allow everyone to read Professor Shi’s own words describing his encounter with Japanese literature, and specifically that of Haruki Murakami, as a young person himself, and thus feel the warmth of his nature directly.

Quan Hui (Editorial Director, Waseda International House of Literature)

Third Time’s a Charm : My Encounter with the Literature of Haruki Murakami

Shi Xiaowei

I encountered my first novel by Haruki Murakami sometime in the early 1980s. I’d just graduated from Fudan University, and I was still there, having just started my career as an adjunct instructor. A fellow research assistant who’d remained at the university like me, the late Wang Jiankang (formerly a professor at Chitose Institute of Science and Technology), was asked to write a review of the new full-length Murakami novel A Wild Sheep Chase. It was another classmate of mine, Ms. Guo Jiemin (presently a professor at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences; hereafter, SASS) who had given him a copy of the original in Japanese for the book review. She had joined the Literature Research Institute at SASS after graduation and was working as an editor at the now defunct magazine Foreign Literature Report while researching Japanese literature there. This was a time when getting one’s hands on foreign literature was still difficult. But Jiankang and I were close—after all, we were first classmates and then became colleagues!—so I was able to read the novel as he worked on the review and got my first real, if all-too-fleeting, taste of Murakami’s literature.

That novel was first published by Kodansha in hardback in October of 1982—it had been previously published in its entirety in the journal Gunzō, but it would only have started to garner attention outside Japan after it was published as a book, I would imagine—but thinking about when it might have plausibly started to become known in China, it seems as though I would have had to have read it sometime after 1983; at the same time, thinking about the nature of Foreign Literature Report, which lived and died by its timeliness, I couldn’t have read it any later than 1984.

After that, I had a period of complete lack of contact with Murakami’s work. Perhaps my own fickleness was to blame—a “lack of consistency,” as one might put it in Chinese, or a tendency to be “like a rolling stone,” to borrow a phrase from the British. In any case, though it’s rather embarrassing to admit now, I spent my time doing various things I no longer care to recall, using contemporary Japanese literature as a tool to eke out a living, reading this book and that, but, like someone who wrote an essay on Japanese waka, and then wrote an essay debating Chinese-style poetry for his next piece, I somehow ended up going about my work during this time without reading Murakami at all.

It was in 1989, while at Waseda University as an exchange student, that I finally encountered Murakami again. I remember with such clarity those first days of my exchange, being shown around by Mr. Takashi Itō, who worked at Waseda’s International Office, and meeting my advisor, Professor Tenyū Takemori, in his office. As soon as he heard my report on my research plans, he said to me in his habitually lofty manner, “Well, you better be ready to kill yourself studying.” And that evening, perhaps as a way to reward me for my hard work in advance, he treated me to a great feast at the restaurant at the Ōkuma Auditorium. This historic building that held countless memories and stories from Waseda’s long and turbulent past has now been torn down, disappearing without a trace.

In the days that followed, just as Professor Takemori predicted, I indeed spent my time killing myself studying, but somehow I did manage to steal a bit of time to read books unrelated to my graduate school entrance exams. One of these was Murakami’s Hear the Wind Sing. During the three and half years I spent at Waseda, I had the good fortune to live in Hōshien Dormitory; leaving its rear entrance, one would encounter Waseda Avenue, which was lined on both sides with a wonderful profusion of used bookstores. These days, most of them have been replaced by tall, gleaming new buildings, but my impression is that the used bookstores of old made the avenue feel more crowded with businesses than it does now, while also lending it a harmonious atmosphere, making it a space that warmed the heart just to walk through. I found Hear the Wind Sing peeking out at me from amongst the 100-yen paperbacks lined up on a rolling cart in front of one of such bookstore, and I bought it.

After that, I bought one Murakami book after another, from Norwegian Wood to Kafka on the Shore, and used whatever free time I can find to read them. I bought Norwegian Wood at a temporary, tent-like stall set up by a used bookstore near the second-story exit of Kashiwa Station on the Jōban Line that I frequented so much it was basically my second home. It was the hardcover’s twenty-fourth printing, dated October 14, 1988; the first printing came out on September 10, 1987, only thirteen months previous, which should tell you just how popular the book was. Sold in two volumes, one cover bright red and the other deep green, the book’s suggested retail price was 1,000 yen, but I bought them for 210 yen each. On top of that, at the time the book came out, there still was no sales tax in Japan; that only started the following year, 1989. I remember that I bought Kafka on the Shore at a large bookstore in Suidōbashi next to the Tokyo University Economics Department. The store’s name was Ayumi Shoten, I believe, and I bought the book when it was newly out, a hardcover as well. The first edition was released on September 10, 2002, also in two volumes, which cost 1,600 yen each. Besides those two books, I’ve collected all the rest of his books as well, some in hardcover and some in paperback, and they sit even now on my bookshelf, lending their support to university education and academic research in China.

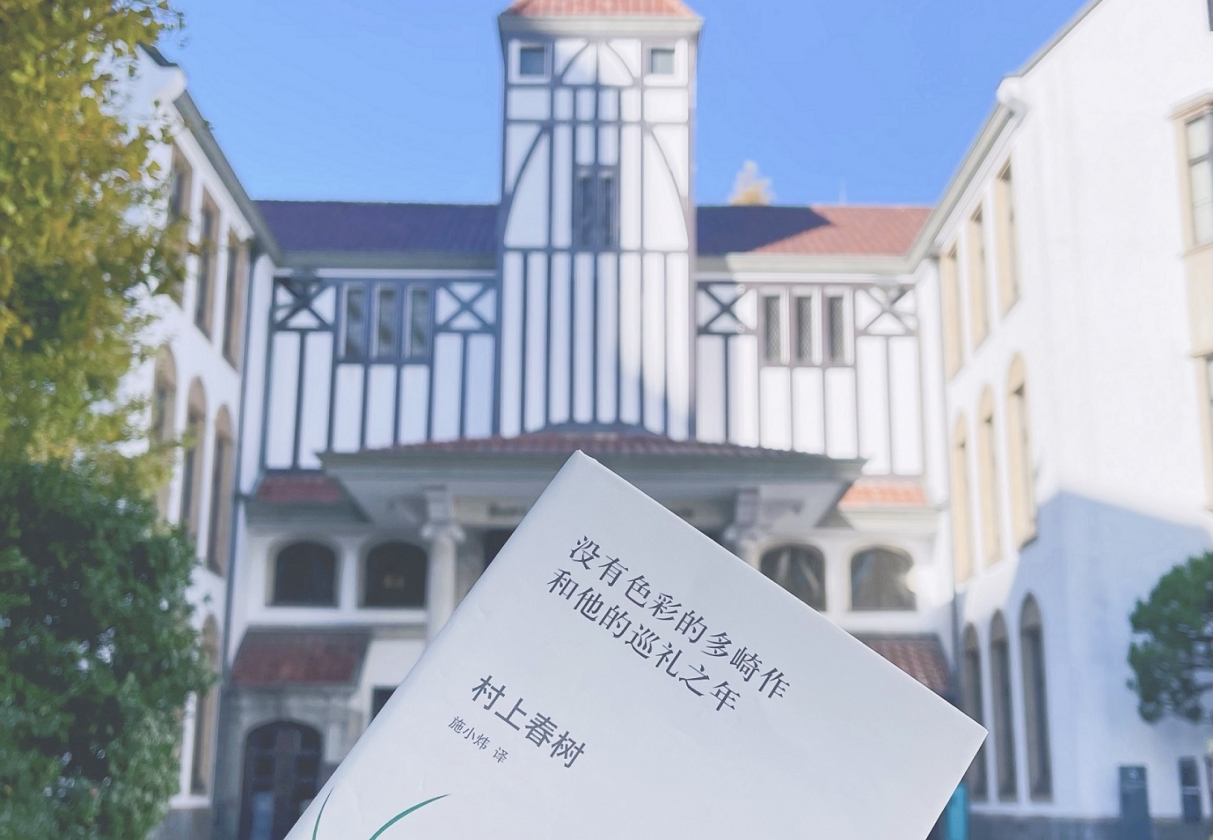

The author during his time as an exchange student, on Waseda campus in front of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum (Enpaku) (Near the present-day location of the Haruki Murakami Library)

When I was wandering through Murakami’s world, I had never dreamed that I would some day end up translating his works. After bidding farewell to Japan, my home for eighteen years at that point, “singing the song of home while waving goodbye to my adopted land,” I returned to China only to find myself, if only by chance and through tenuous connections, encountering Murakami’s literature for a third time. But this turned out to be the deepest, richest encounter of all. By which I mean, by some kind of miracle, I was able to embark on the work of translating Murakami’s literature into Chinese. My attention then naturally turned to the reception of Murakami in China, but this work also led to a particular discovery.

First of all, in China, the main way of thinking about Haruki Murakami was as the “Godfather of the Petit Bourgeoisie,” and his literature as “Petit Bourgeois Literature.” This sort of reading is, it goes without saying, completely different than how he’s read by readers in other countries and cultural contexts, but while this reading definitely displays a certain “Chinese uniqueness,” it’s important to remember that the “petit bourgeois” label is one that was used most often during the reign of Mao Zedong, which climaxed with the Cultural Revolution; in that sense, it’s a label that doubles as a criminal charge. Everyone trembled in fear of that label being affixed to them out of the blue by, in the early period, a Party Secretary, or, later, a member of the Red Guard. If that happened, not only you, but your family and loved ones as well, would be dragged down to the very depths of hell as punishment.

However, during the 1990s, a fundamental shift began to occur within the meaning of “petit bourgeois.” Perhaps because “revolution” was no longer the object, for many young people—and a certain segment of not-so-young people, too—the term became aspirational, an honorary title to adopt for oneself. By contrast, in Japan at the time—that is, in the Japan depicted in Murakami’s novels—the term “petit bourgeois” had fallen out of general use entirely. Of course, the shortened version of the term, puchi buru, existed historically, but as a term meaning much the same as the “petit bourgeoisie” demonized during the Mao years; in contemporary Japan, it had become a more or less dead phrase, the number of people who might use it numbering nearly nil. The nonexistence of a word represents the disappearance of a concept, one might say, which means that the average Japanese reader wouldn’t read a Murakami novel with an eye toward diagnosing the puchi buru nature of the protagonist; further, Murakami himself most likely had no intention of drawing a portrait of the Japanese petit bourgeoisie when he sat down to write his novels. Of course, as Roland Barthes said, “Les auteurs son morts”—authors are dead. By which he meant that in the interpretation of texts, the author himself is absent, as if dead. In this way, readers are given full rein to interpret texts as they will, but in China, especially in the interpretation of foreign texts, it is impossible to deny that sometimes there might be certain stratagems at work beneath the surface to encourage specific kinds of misinterpretations, which we should recognize as such and work to correct.

Another kind of misinterpretation of Murakami is to dismiss him as “nothing more than a bestseller author” or his literature as simply “popular literature.” This is a misinterpretation that can be counted among the reasons why Murakami’s creative strategy is misunderstood, in my opinion. Murakami himself has explained that his ultimate goal is to smuggle “pure literature” content into the “structure” of “popular culture”—all glosses of terms that he chose himself—in order to create a sōgō shōsetsu; that is, a total novel. And he has succeeded, perhaps all too well, in this fusion of elements, for his novels have consequently gone on to sell at an unprecedented rate, while at the same time, many people, some “professional readers” (that is, researchers and critics) included, have been fooled by the camouflage of “popular culture” in a way that negatively affects their assessment of his work’s “pure literature” content. If only these sorts of preconceived notions could be jettisoned, the artistry and intellectual content of Murakami’s novels could be properly recognized.

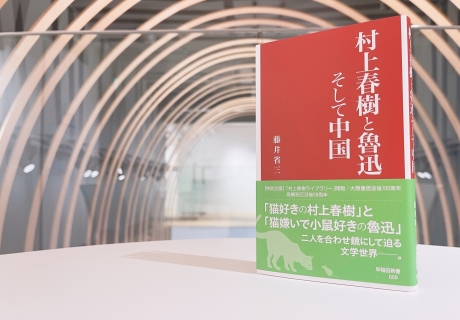

After my third encounter with his work, my understanding of it naturally deepened as my professional relationship to it did, too—to the point that it might even be said to have gotten “out of control” (laughs). Finally in December of 2014, it had come as far as my organizing an international symposium on Murakami at my home institution. We set the theme as direct as it can get: Murakami and China. The symposium’s roster of presenters included two scholars from Japan, Professors Mamoru Yamaguchi and Shōzō Fujii; Professor Michael Emmerich from the U.S.; and three Chinese scholars; the symposium itself included forty scholars and researchers from all over China, making the event a resounding success. Following the symposium, a series of various events transpired, after which we were finally able to gather the presentations together into a special issue of the university’s research bulletin that came out at the beginning of this year. This has been my proudest achievement since my encounter with Murakami’s literature, one that proves the old saying true: the third time was, indeed, the charm.

January 11, 2022

Profile

Born in Anhui Province, Shi Xiaowei graduated in February 1982 from the Japanese Literature Department in the Faculty of Foreign Literature at Fudan University, and then, after working at Fudan University as an adjunct lecturer and researcher, he came to Japan in October 1989 as an exchange student on a scholarship from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (as it was known then) to study at Waseda University’s Literature Department Graduate Program. He reached the last stage of the doctoral program in March of 1995, and then he left the program [as is customary in Japan]. After working as a lecturer in the Humanities and Sciences Division at Nihon University, he returned to China in March 2007. After teaching at Sanda University in Shanghai, he retired in September 2020. He has published twenty-four books in Chinese and Japanese, and translated forty-three Japanese novels into Chinese; thirteen of these are novels by Haruki Murakami.

*This article was made possible through the support of the Waseda International House of Literature and Top Global University Project in collaboration with Waseda University’s Global Japanese Studies.

Related

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Rebecca Brown

2025.12.02

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Camilla Grudova

2025.10.20

-

Memories of Things That Never Happened to You

2022.12.12

- Hideo Furukawa

-

Historical Consciousness and “Boomerang” Thoughts in the Works of Haruki Murakami

2022.05.08

- Tetsurō Koyama

-

Useful Landscape

2022.03.28

- Ryō Mizuhara

-

My Personal History with the Literature of Haruki Murakami

2022.02.25

- Shōzō Fujii