Collective memory as a social experience

I am a US born researcher currently studying collective memory in the Mekong area, focusing on Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia. Before my doctoral studies, I worked for education NGOs in Cambodia. This experience prompted me to study education and society in Southeast Asia.

Collective memory, different than individual memory, is a social experience and recalled externally with references to identity, language and symbols. It can also be explained through subjective accounts of the past, framed in the present based on historical memory and/or autobiographical memory. Memory takes place with social materials, within social contexts and in response to social cues, and collective memory is ever changing, dynamic and variable. Studying collective memory, therefore, is to identify shifting social frames over time.

A typical example of collective memory comes from an anecdote after Japan was defeated in the World War II: school children were told by teachers to paint out certain lines in their text books because they were not supposed to be remembered anymore. This anecdote exemplifies the dynamic, ever changing nature of history and collective memory.

What is the Mekong?

The reason I’m interested in the Mekong as a location to study collective memory is because it has a long history of various Kingdoms growing and shrinking over time, influenced by China, India and Sri Lanka. This background resulted in the Mekong’s population being diverse, both ethnically and linguistically. This area also has about 100 years of French and British colonialism, and modern nation-states are relatively “new”. On top of this, the region faced a brutal history during the American War, or the Vietnam War from American perspective, where anti colonial and nationalistic ideologies triumphed in 1970s.

The Mekong has also experienced a large amount of development aid and assistance. Western countries have been the primary benefactor in recent decades, but China is increasingly spending a lot of money. This has effectively created a proxy struggle between China and West. For all these reasons, the diverse and contested nature of the Mekong region makes it an excellent location to study collective memory.

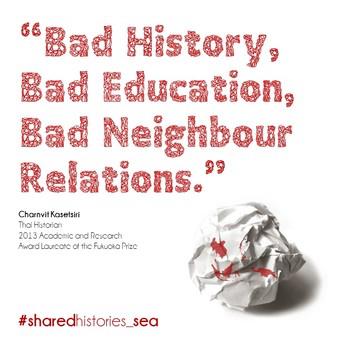

At the same time that there are contested national collective memories across the Mekong, there is an intergovernmental organization called the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) actively trying to construct a regional identity. This is happening through ASEAN’s plan to create a Socio-Cultural Community by 2020. The basis of a Socio-Cultural Community is in seeing similarities – and not differences – across the region, and is being made through UNESCO Bangkok’s Shared History Project, which is developing lessons that countries can incorporate into their curriculum. That means the social frame must change between a national and regional collective memory. My study looks at how that is happening.

An UNESCO’s project called Shared History Project was started to construct ASEAN identity.

Schools as an entry point

Collective memory is linked to what Benedict Anderson called “imagined communities,” which are communities constructed through museums, censuses, and schools. Among these, as a comparative educationalist, I have focused on schools as an entry point. Textbooks are important in studying the way in which an imagined community is created through schools, so what I did first was to look how various countries in the Mekong construct official memory through citizenship, moral, and history curriculum.

In our analysis, we focused not only on what is actually written, but also what is hidden, what is implied but not necessarily specifically stated, and on what is absent. We call the last point the “null curriculum” and are asking questions such as why it is the case something is absent from the text and what it means that these topic are removed.

After the textbook analysis, my team and I started conducting interviews with policy makers who make the curriculum, both nationally and regionally. How do policy makers understand collective memory, how do they understand national identity, and how do they understand regional identity and regional formation? I am going to different countries and meeting different policy makers, trying to understand from their perspective what collective memory means in different countries.

What I am currently doing is at the policy level. The practice of teachers and students inside schools can be very different from what policy makers discuss and believe. In the future, I plan on conducting public opinion surveys and interviews of teachers and students to understand how collective memory is understand by these actors.

Exclusion and xenophobia

The preliminary findings thus far suggest that despite the shifting social frames brought on by the concept of shared histories, collective memory in the Mekong is primarily framed in terms of nationalism. Discursively, the regional social frame of collective memory focuses on commonalities and non-political issues, but UNESCO Bangkok’s organization means collective memory is, practically speaking, still based on the nation. Theoretically, Anderson’s idea of an inclusive imagined community based on a common language is limited in the Mekong today. Exclusion and xenophobia seem to be the main ways to construct collective memory. Until a regional collective memory is seen as a political project, any attempt at creating a sociocultural community will continue to reinforce nation-state divisions.

Conclusion of my research to date

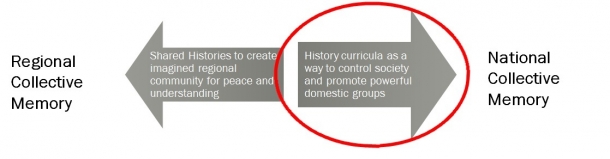

To simplify the conclusion according to the chart above, I would say on the one side (left) we have shared histories used to create a regional community based on peace and understanding. This is UNESCO Bangkok’s idea of regional collective memory. On the other side (right), there is national versions of history that are used to control society and promote powerful domestic groups in an attempt to create a national collective memory. I don’t know if this tension has to exist and I don’t think it necessarily does. But this is certainly the way people see it in the Mekong, and I would argue it’s right side that is currently winning

To put this in a global context, we see xenophobic nationalistic ideologies becoming more prevalent today than they were, say, twenty years ago. So, this study provides some empirical evidence as to how this movement to xenophobia is happening and how exclusion actually becomes the dominant way of understanding group identity. All history is a history of the present. It is the current regime in power that writes the history of the past, and that writing can change depending on who is in power and what ideas are deemed most politically needed.

取材・構成:益田美樹

協力:早稲田大学大学院政治学研究科J-School