Phrenology as a “Science” of Character Formation

In 19th-century Europe, there was an avid interest in trying scientifically to explain human character, resulting in the emergence of several interesting theories. My research focuses on one of these: phrenology. Phrenology theorized that human character was revealed in the shape of the cranium and the head. While now scientifically debunked, phrenology experienced a tremendous boom, particularly in England in the first half of the 19th century.

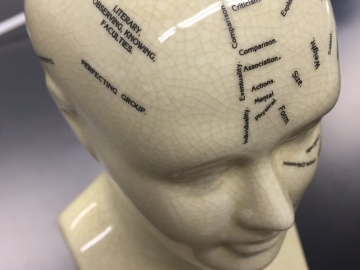

During my doctoral program, I was engaged in research on a completely different topic in European history and the history of thought. In my research on the English philosopher John Stuart Mill, I came across criticisms of phrenology in a number of his works. Furthermore, while I was studying in London, I found a phrenology bust (Photo 1) for sale and became interested in finding out what, exactly, phrenology was. During that investigation, my interest was stirred again and again, as I wondered why Mill had been so critical of phrenology and why phrenology spread as it did in 19th-century Europe. Thus began my current research. While phrenology is interesting in and of itself, my research is concerned with the social context in 19th-century Europe within which phrenology was enthusiastically received and then abandoned.

Photo 1: Phrenology bust. On each area of the head is written the character trait or aptitude governed by that area. (Courtesy of Associate Professor Yuichiro Kawana)

Observations on the skull shapes of patients, criminals, and priests

The founder of phrenology, the German physician and anatomist Franz Joseph Gall, noticed through observation and dissection that people with similar predispositions had heads with similar shapes. He believed he had discovered a relationship between a person’s character or disposition and the shape of their skull. He then expanded his data collection beyond patients, for example, by closely studying the shapes of the skulls of criminals. He found that a common attribute of their skulls was a mound above the ear, which led him to believe that there was an organ governing the propensity for criminal behavior in that part of the brain (Fig. 1). He also collected data on the skulls of priests; he observed that the area at the top of their heads was often prominent and concluded that there was an organ governing piety and religious sentiments in that region. The fact that Gall was a famous physician contributed to phrenology’s gradual popularization. During that time, the graves of famous composers were even robbed to look at the shapes of their crania to try to understand which area of the brain governed musical talent.

Figure 1: Areas of the skull governing the functioning and character of criminals (left) and priests (right). (L. A. Vaught, Vaught’s Practical Character Reader, Chicago, 1902)

Phrenology was most popular during the first half of the 19th century in England, where even Queen Victoria had a phrenologist examine the heads of her children. Phrenology enjoyed a tremendous boom; reportedly, it was even used to forecast children’s futures, select marriage partners, and evaluate job applicants. In an actual examination, a phrenologist would examine the shape of the person’s skull with his fingers and palms, measure the size of the head and, based on the results, diagnose the person’s character and proclivities. A market even developed for helmet-shaped devices to correct the shape of the head in order to change one’s character.

However, the popularity of phrenology declined beginning in the 1850s. Due to developments in anatomy, experimental psychology, and other fields, the fact that phrenology was unscientific became widely accepted. It fell into disuse for lack of advocates.

Why did phrenology become popular?

However, even during its heyday, phrenology was not generally considered to be scientifically correct. Many of the people considered part of the intellectual elite, starting with Mill, were critical of it. For people who were swept up in the phrenology boom, it may have been close to palmistry or to associating personality with blood type (as is common in East Asia).

So why did phrenology become so popular in England in the first half of the 19th century? From my research to date, I have found a few social factors that may explain people’s susceptibility to believing in it. First, English society had developed economically due to the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th century. Working-class and middle-class people had progressed economically, which gave them the flexibility to focus on their children’s education and to think about improving their own character to reflect their new social status. Furthermore, as industry was developing in Europe, nation-states were being established, and the concept of national or ethnic character spread as interest turned to finding the inherent character of each nation or race as a group. The evolution of discussions about how national or ethnic character was determined may also have led to interest in phrenology.

Discussions about the nature of human character had been taking place long before this time. For example, Descartes’s mind-body dualism contended that the mind and the body were independent, separate entities, with the mind thought to be something immaterial and invisible. By contrast, Gall tried to explain character from an anatomical perspective by carefully observing something visible: the shape of the head and the cranium. The end of the 18th century saw a movement toward positivism, which held that arguments needed to be based on empirical facts from observations and experiments rather than on metaphysical extrapolation. This fact, too, may have been a factor in the popularity of phrenology.

Disagreements over the science of character formation

The theories and doctrines related to the science of character formation and their relationships can be mapped as in the diagram in Figure 2. I am focusing on four theories—Mill’s incomplete theory of ethology, which tried to scientifically systematize the mechanism for character formation; Owenism, which argued that character was entirely environmentally determined; criminal anthropology, which held that criminals were born with a criminal nature; and phrenology—in an investigation of how they conflicted with and influenced each other.

For example, in Owenism, childhood education was considered most important because Owenites believed that at birth, character had yet to be developed. Phrenology espoused the opposite: because the shape of the cranium was hereditary, character was thought to be determined by nature. If character is determined by education or birth, as was believed by followers of Owenism and phrenology, respectively, individuals can do nothing about their own character, because education is something provided by parents, and one cannot choose to whom he or she is born. Therefore, those who commit crimes, even if they are adults, have no responsibility for their actions, a conclusion that Mill found ridiculous. Meanwhile, criminal anthropology and phrenology are directly related in their hereditary view of criminality. For example, they contend that criminals share physical characteristics, such as the shape of the head, and that the criminal character is atavistic. This mapping in this diagram is still incomplete, but I intend to clarify the relationships in more detail after further research.

Figure 2: A diagram of the correlations among European theories and doctrines related to the science of character formation from the end of the 18th into the 19th century. My research is primarily focused on the relationships among phrenology, Owenism, ethology, and criminal anthropology. (Courtesy of Associate Professor Yuichiro Kawana)

Interview and Composition:Chisato Hata

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School