疑問1“自分で考える力”って、結局なんですか?

InstagramやYouTubeで一度何かを調べると、すぐに広告などに反映されるのに驚きます。買い物をするときも、そういった広告に無意識に感化されている気がして、自分の判断は周りに影響されたものにすぎないように感じます。その一方で、大学に入学してから「自分で考える力を身に付けて」とよく言われますが、そもそもこれはどんな力なんでしょうか?

自分? そんな実体は存在しないのでは?

答えてくれる哲学者

流行に異を唱える、徹底した懐疑主義者

デイヴィッド・ヒューム David Hume

(英国/1711〜1776)

この質問で問題となるのは、「自分」で「考える」とは何かということです。哲学の大きなテーマでもあるので、じっくり探ってみましょう。

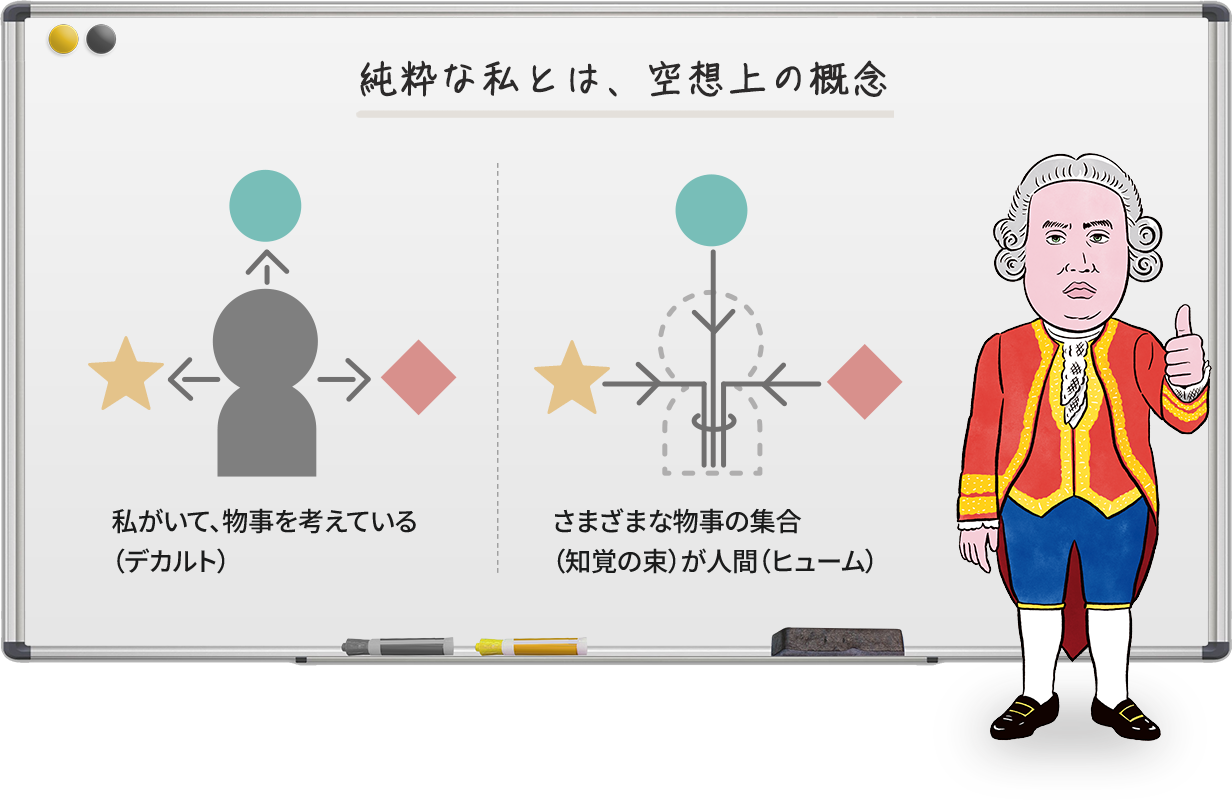

フランスの哲学者・デカルトは、有名な「われ思う、故にわれあり」という考えを、近代哲学の出発点として設定しました。この「考える私」を最優先に、「100%純粋な私」から出発する理論的思考は、現代に至るまで科学や社会をけん引。だから大人は、「自分で考える力を養いなさい」と連呼するのでしょう。

このデカルト以来の考えに異を唱えたのが、英国の哲学者ヒュームです。彼は著書『人間本性論』の中で、私たちが「考える私」としてイメージしがちな精神的実体は、「知覚の束」にすぎないと大胆に看破。自分自身を構成しているのは、目や耳などを通じて得られる情報(知覚)であり、そうしたものに基づかない実体としての私など、フィクションのようなものだと訴えたわけです。

この「実体」という言葉は哲学の重要用語で、他の何にも依存せずに、それが存在するという意味です。つまりヒュームは、「何にも染まっていない自分なんて、そもそもいない」と考えた。質問者の問いに対し、彼ならば「まっさらな『自分』がいるはずだという先入観が、悩みの原因だ」と答えるでしょう。確かに突き詰めてみると、私たちは言語や文化、育った家庭や地域の影響などを受けて、日々思考を繰り返しています。「100%純粋な私」とは言えないですよね。

だから質問者の方は、そこまで「自分で」考えることに不安を抱かなくてもよい気がします。もしかすると、自分で考えていない、あるいは本音では自分で考えてほしくないと思っている大人たちが、「自分で考えろ」という教育をしてくる、現代社会の矛盾に異議を唱えたい気持ちがあるのかもしれません。そんなとき、ヒュームの考えは強い味方になるのではないでしょうか。

疑問2ワンオブゼムではなく“何者か”になりたいです。

自分は将来、「何者かになりたい」と強く感じます。一方で、「今の自分のままでいい」と、楽な選択肢に流されそうになることも。ありきたりなワンオブゼムとして死んでいくという、漠然とした恐怖も抱きます。この広い世界で、私は何者になればいいのでしょうか。

もう既に、あなたは「何者か」なのです。

答えてくれる哲学者

暴力に抗う、優しきインドの哲学者

アマルティア・セン Amartya Sen

(インド/1933~)

質問者の方が言う「ありきたりなワンオブゼム」は、アイデンティティを失った状態ともいえます。この「アイデンティティ」というワードから、問題を考えてみましょう。

アイデンティティは哲学用語で「同一性」。辞書的な意味は、個人が変化や差異に対し統一性や独自性を保ち続けることです。私たちは日常的にアイデンティティという言葉を使いますが、どこか「アイデンティティは、一人につき一つ」といったイメージがありますよね。これも辞書的な「自己同一性」が影響しているのでしょう。

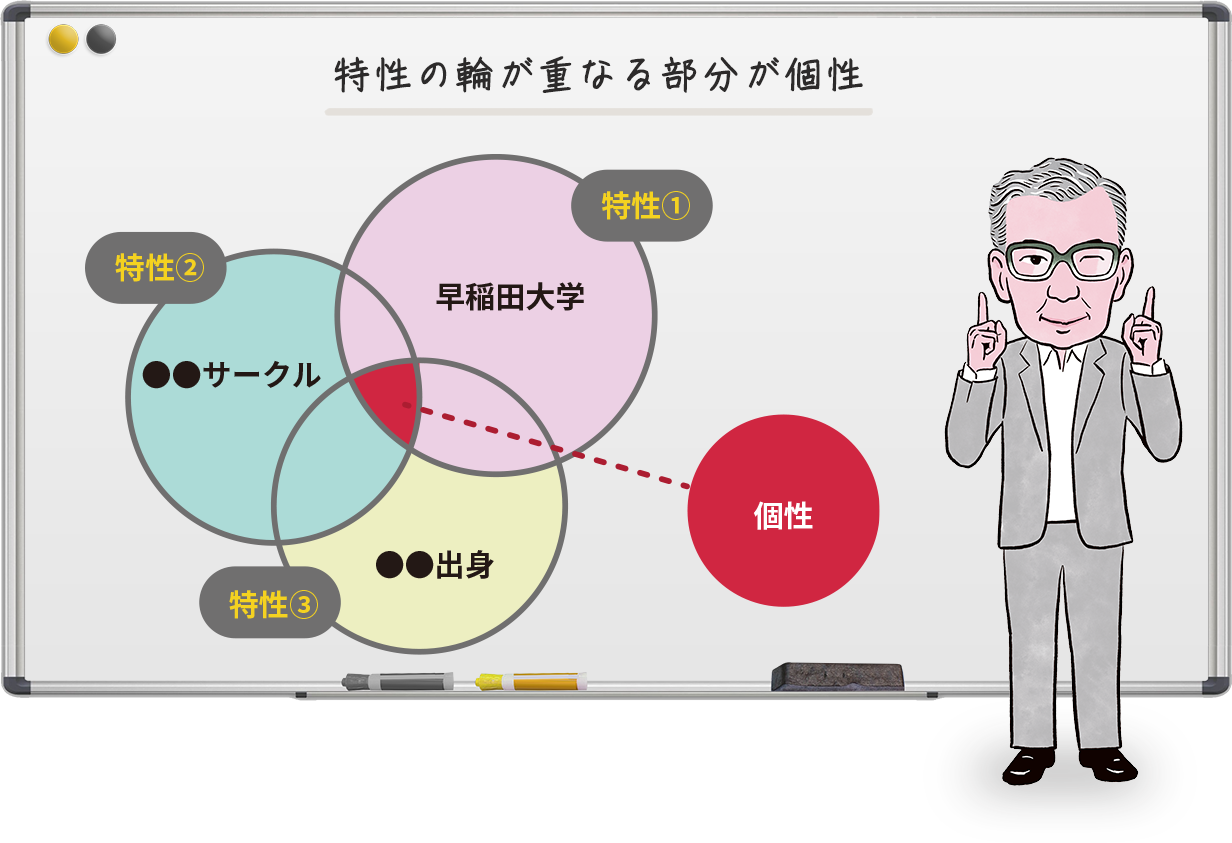

しかし、現代インドの哲学者であるセンは、ちょっと違う角度からアイデンティティを捉えました。ノーベル経済学賞の受賞者で、貧困や暴力などの問題にも立ち向かった彼は、『アイデンティティと暴力』という本の中で、アイデンティティを「他人との同一性」という意味で使用します。「自己同一性」に対して「他人との同一性」ですから、かなり不思議に映りますね。しかし、私たちは他人とさまざまな「同一性」を持ち、その重なり合いの中心を生きているというのが、センの考えです。自分に置き換えてみると理解できるかもしれません。

皆さんは、早稲田大学に在籍したり、サークル活動やアルバイトを行っていたり、出身国・地域があったりと、複数の特性を持っています。趣味や性別、居住地なども同様です。そしてそれぞれの特性は、他の人も持ち合わせています。早稲田の学生は、あなただけではありませんよね。

センが画期的なのは、特性の重なり合う部分が「個性」だと考えた点です。そして特性が多く複雑であるほど、個性がはっきりすると言います。例えば文学者のゲーテは、詩人でありながら、政治家、自然科学者、画家でもあり、さまざまな特性を有しています。ゲーテがいなくなれば、同じことをできる人もいなくなる。だからゲーテは個性的と唱えた他の哲学者もいました。

センのアイデンティティ論を、自分に当てはめてみてください。質問者の方は、既にさまざまなアイデンティティを持ち合わせ、もう「何者か」になっているのです。しかし、この答えではきっと満足しないはず(笑)。そこで実践すべきこととして、私からは二つを挙げることができます。一つは、なるべく多くの物事に関わり、活動範囲を広げる。つまりアイデンティティとなる特性を増やすことです。もう一つは、特性を強化する、つまり自分が夢中になれる、関心の高い物事に時間を割くこと。さまざまなアイデンティティのうちの一つを、徹底的に掘り下げてください。すると新しい道が開け、強力な「何者か」になれるのではないでしょうか。

疑問3対人関係の中で生じる理不尽に、どのように対処すべきですか?

アルバイト先でルールを守らない人がいるせいで、私まで怒られることがしばしば。理不尽だと感じます。一方で、私自身、つい相手に腹を立ててしまうことがありますが、そこで逆上したら自分も理不尽な存在になる心配もあります。そんなときにどう対処すべきか。考え方を身に付けたいです。

現実で起こる理不尽は、現実の中で対処しよう。

答えてくれる哲学者

着実な前進を重んじる現実主義者

ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

(ドイツ/1770〜1831)

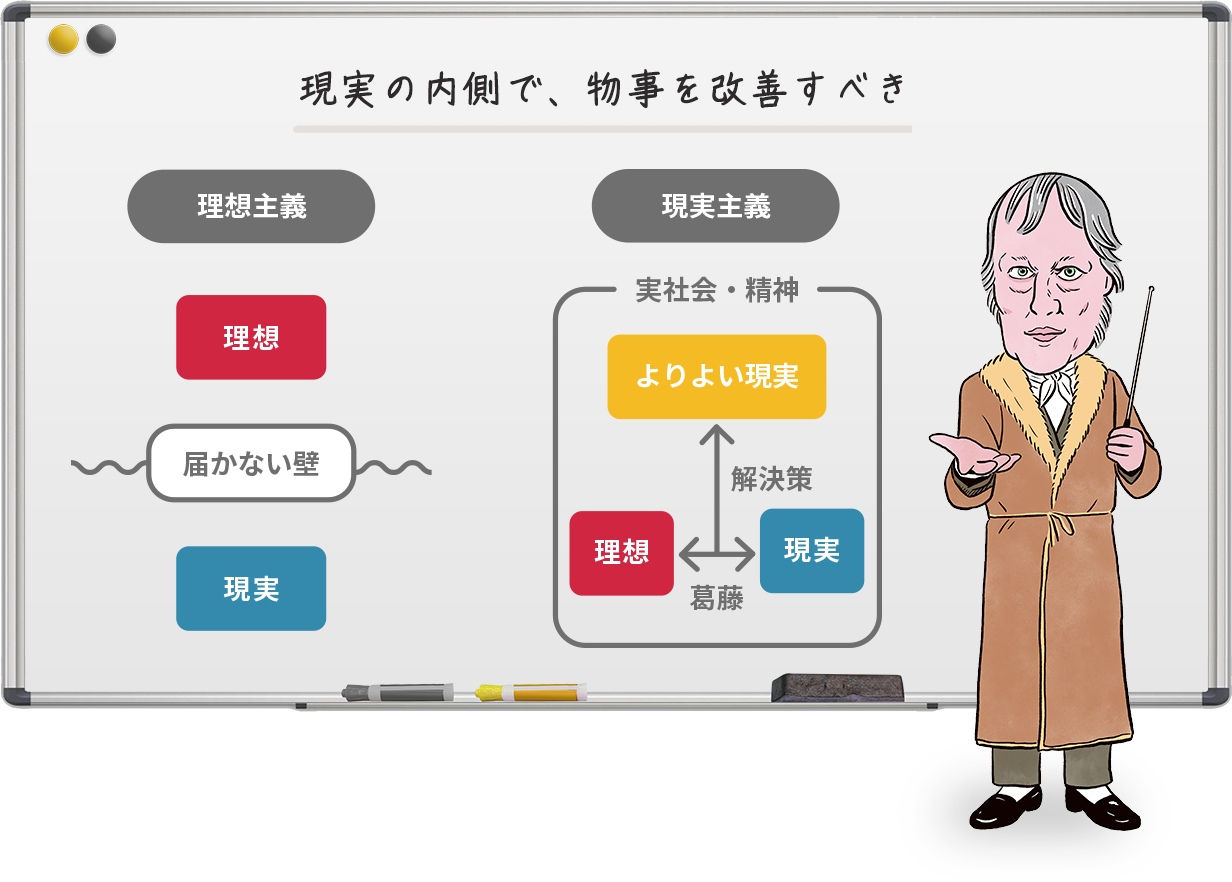

理不尽というのはおおむね、理想に反し、現実世界で理屈が通らない物事に対して感じるものではないでしょうか。その点において、質問者の方は理想主義的な視点の持ち主だといえます。ここで役立つのは、現実主義者のヘーゲルの考え。彼の視点が、発想の転換をもたらしてくれるかもしれません。

まず、哲学の世界で古代からある2大ストリームについてお話しします。理想主義と現実主義です。「理想と現実にギャップがあるなら、理想を志向しよう」というのが理想主義。その代表格が、古代ギリシャのプラトンや、近代ドイツのカントです。例えばカントは「仮に嘘(うそ)をつかない人間がこの世に一人もいなかったとしても、なお人間は嘘をつくべきではない」のような思考の持ち主です。

一方、「腹を立てるのも現実世界の中なのだから、その理由も現実にある。現実の中で向き合おう」というのが、現実主義。ドイツのヘーゲルはその代表格です。彼が活躍したのはフランス革命以後の、ヨーロッパ全体が理想に燃えていた時代でした。当時フランスで、ロシアに内通したと疑われる詩人に対し、ある青年が腹を立てて刺殺する事件が起こります。抹殺というのは、理不尽な現実から理想の世界へと移行させる、理想主義の極端な例ですが、このときフランス国内で青年を擁護する意見が盛り上がります。しかしヘーゲルは、フランスの世論を浅はかだと一蹴。抹殺のようなテロリズムに走るべきではなく、なぜスパイ嫌疑のような問題が起こるかに対峙(たいじ)し、現実の中で解決策を探るべきだったと主張しました。

彼の有名な言葉が、「理性的なものは現実的なものであり、現実的なものは理性的である」。この発想に基づいて、現実そのものを否定せずに理不尽を改善していく態度を重視しました。現実と理想を分けて考えないのです。

理不尽なことが起きた際、まず腹を立てなければ、世の中は良くなりません。例えば現在、ハラスメントを社会問題として語れるようになったのは、これまでに腹を立て、声を上げた人たちがいたからです。一方、自分の理想だけを掲げ、現実的な解決方法に向き合わないでいると、物事は前進しない。そんな視点を、ヘーゲルは教えてくれます。まずは自分が腹を立てている理由を徹底的に掘り下げ、対話や交渉、法的措置、選挙など、現実にある人間関係の中で、世界を改善していく。そうしたアプローチが重要なのではないでしょうか。

疑問4なぜ、この世界から戦争はなくならないのでしょうか?

ウクライナやパレスチナをはじめ、世界では紛争が絶えません。過去に人類は悲惨な戦争体験をしてきたにもかかわらず、21世紀になった今も、世界平和が訪れないのはなぜでしょうか。世界の人たちが皆仲良くすることは不可能なのでしょうか。

皆仲良くは、本当に平和につながるのか?

答えてくれる哲学者

人権と向き合った理想主義者

イマヌエル・カント Immanuel Kant

(ドイツ/1724~1804)

戦争と平和は人類にとっての最重要テーマですが、この質問において考えるべきポイントは、「皆仲良くすること」が、本当に平和の条件かどうかでしょう。今回私たちにヒントを与えてくれるのは、先にも登場したカントです。

矛盾を許さない徹底した論理で、近代哲学の礎を築いたカントは、晩年に『永遠平和のために』という著書を残しました。「永遠平和」とは、二度と戦争が起こる可能性がない状態です。その実現に向け展開されたのは、「皆仲良く」といった博愛精神の尊重ではなく、自由を保障する“権利”の話でした。どういうことでしょうか。

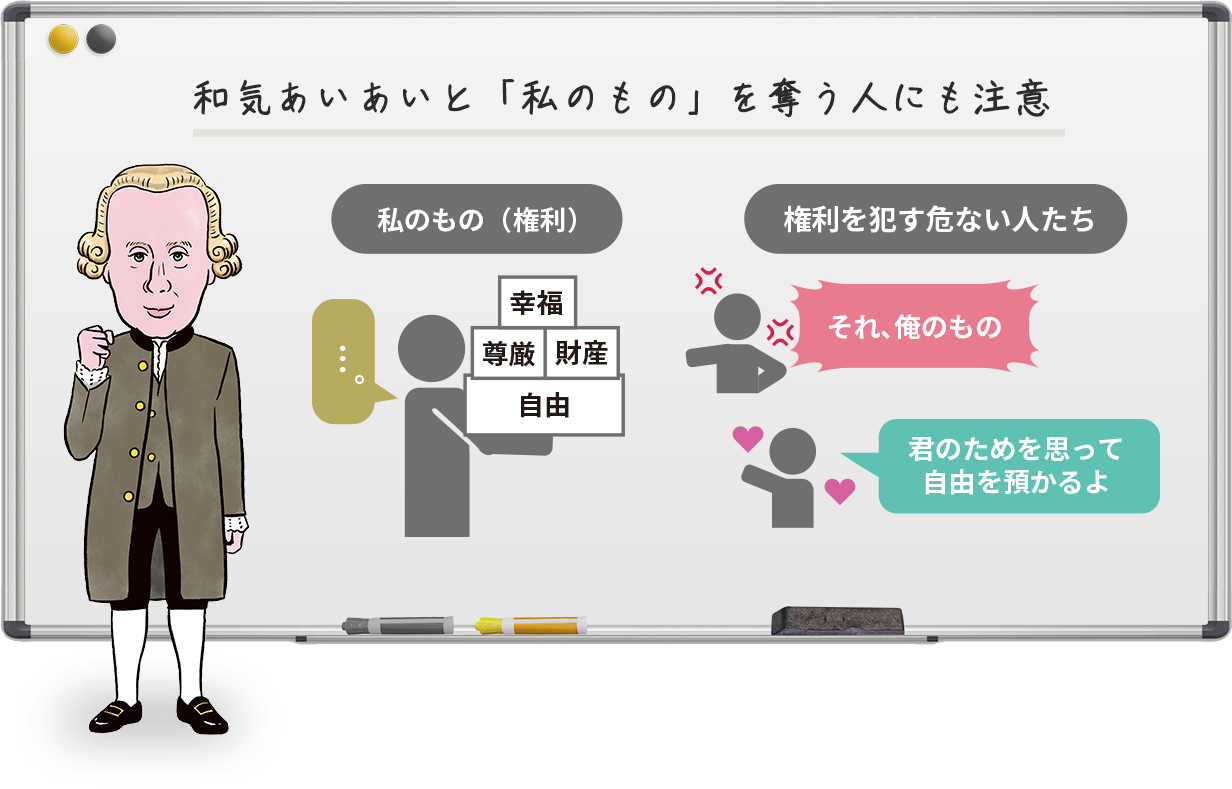

権利というのは、「私のものと、あなたのものは、違う」ということ。皆さんも、他人から自分のものを奪われそうになると「ノー」と主張しますね。「皆仲良く」が良くないのは、「私のもの」と「あなたのもの」の境界がいつの間にか曖昧になり、その状況を利用して権利を奪おうとする者が現れるからです。そしてカントは、権利の最も根底にあるのは、自由だと考えました。「私の自由」と「あなたの自由」との区別が根幹にあり、その上に他のさまざまな権利が存在する、と。

個々の自由を保障するためには、まず国家と法が必要になります。しかし国内で権利が守られていても、戦争により他国から侵害される可能性は拭えません。そこで国家同士が互いの権利を保障し合う国際法が必要になる。こうして永遠平和が実現されていくと、カントは考えます。

なかなかシステマチックな思想ですが、注目すべきは「仲良し」「博愛」に依存しない点。侵略戦争を仕掛ける国が、「同胞を救う」といった博愛論を持ち出すケースは、現代にも見られますね。カントはその危険性を理解していたのでしょう。

このカントの視点を、皆さんも想像してみてください。異国で紛争が起き、地球上の誰かの人権が侵されていて、それを皆が見逃している。そんな世界を生きることは、いつの日か自分の人権侵害も見逃されることを意味します。恐ろしいことです。

権利を巡る諸問題は、今のところ戦争がない現代日本でも生じています。本当に私たちが世界平和を望むのであれば、まずは身近な権利の問題を注視し、立ち向かうべきではないでしょうか。一人一人が目の前の問題に対処し、まっとうな民主主義に沿って物事が進行すれば、その総体としての人類社会も前進するはずです。人類は矛盾を繰り返しますし、戦争がゼロになる日は来ないかもしれません。それでも絶望せずに、前に進む道を考えなければならないのです。カント自身、戦争も植民地支配も奴隷売買もあった時代に、「皆人間なんだよ」と、勇気を持って人権を語りました。現代を生きる私たちは、そんなカントの姿勢から学べることも多いはずです。

疑問5大学での学びが何に役立つか分からない。

大学で日々学んでいても、将来どのように役立つかが想像できません。語学やプログラミングなど直接ビジネスに役立つ学問はまだしも、多くの学問に意義を見いだせないです。そもそも、社会において大学に存在意義があるのか、疑問に感じます。

大学での学びは、役に立たなくてもよい

答えてくれる哲学者

哲学を哲学した20世紀の巨人

カール・ヤスパース Karl Jaspers

(ドイツ/1883〜1969)

20世紀のドイツの哲学者・ヤスパースは、『大学の理念』という本で、大学の学問の根幹にあるのは「根源的知識欲」であると主張しています。これを一言で表すならば、「もはや何のためでもなく、知りたい」という、かなりマニアックな欲求です(笑)。彼に言わせれば、学問は生活やビジネスに役立たなくてもいいんですね。しかし『大学の理念』は、模範的な大学論として今でも評価されています。彼の思想から、大学や学問の意義を考えてみましょう。

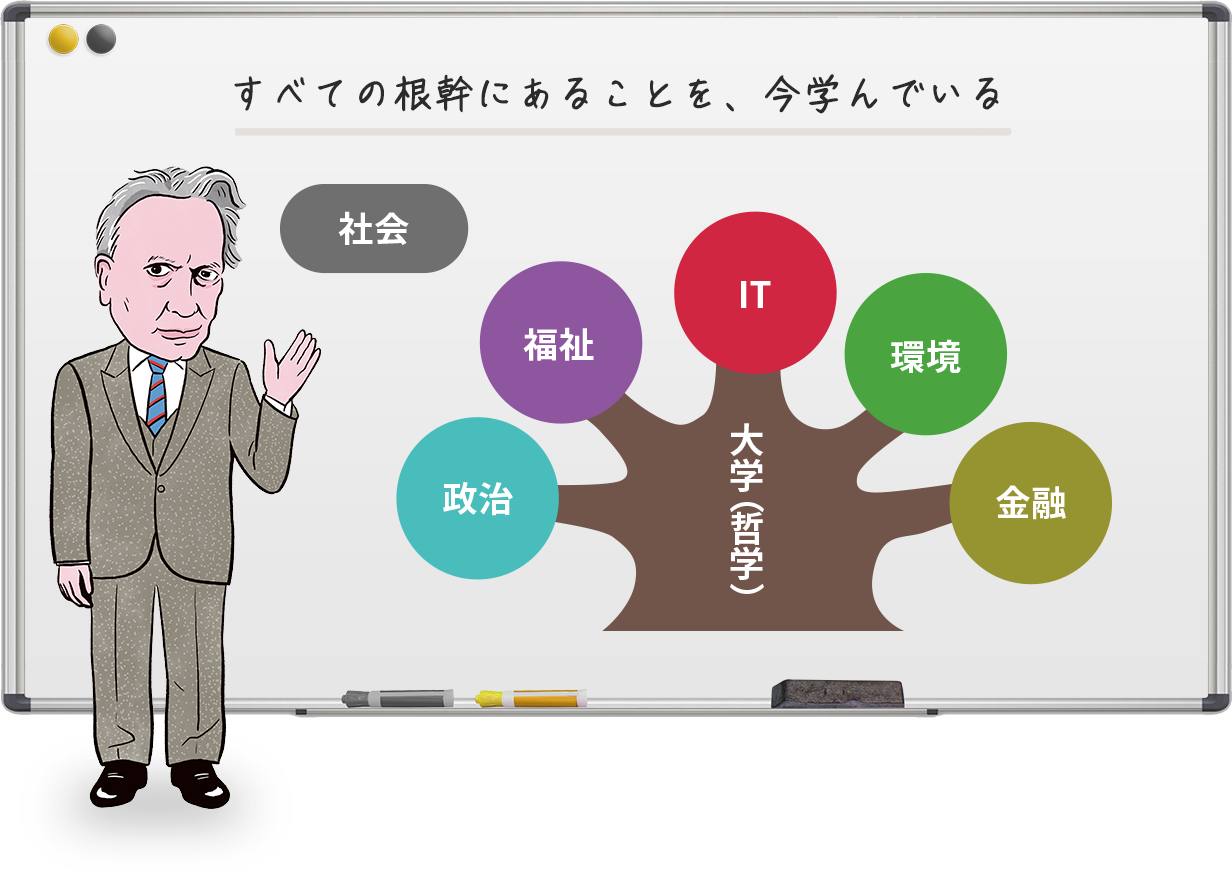

「社会における大学の存在意義」は、「哲学とは何か」という問いと似ています。世の中が一つの樹木であるとイメージしてください。最先端技術や社会的活動に関わる学問は、枝葉の部分。日光に向かって伸びるように、日々進歩しています。「福祉を向上させるのに最適な制度は何か」「地震はなぜ生じるのか」「デフレはいつ止まるのか」と、“問い”に対する“答え”が成果になるのも、こうした学問の特徴です。

しかし時には、「福祉以前の問題として、そもそも幸福ってなんだっけ?」と、木の幹やその根元の部分に戻ることもあります。これが哲学であり、“答え”から“問い”へと向かう、逆のルートを特徴とします。「今何時?」という問いは時計を見れば分かりますが、「そもそも時間とは?」と、答えが存在するかも分からない部分を、わざわざ掘り下げるわけです。暇じゃないとできません(笑)。

大学の役割も、木の幹と似ています。一方の社会は、枝葉の部分。例えば企業は、IT、自動車、金融、福祉と、各方面に分岐した活動に専念することで、新商品や先端技術を開発します。しかし枝葉を進化させ続けると、課題にも突き当たります。例えば今日、生成AIの台頭により「人間が果たすべき役割は何か」が問われているように、根幹に立ち返るべき瞬間が訪れる。経済格差や環境、人権問題も同様です。このとき、社会における大学の役割が発揮されるのでしょう。

もしも質問者の方が将来、ビジネスパーソンになるならば、必ず利益を追求するはずです。しかしある日、「その利益追求は何のためか?」と自問し、例えば「人々の幸福のため」と答えるときが訪れる。さらに突き詰めると、「幸福とは何か」という問いも生じるでしょう。社会人であっても「根源的知識欲」はなくなりません。既に古代ギリシアの哲学者・アリストテレスが記しているように、人間とはそうした生き物なのです。そして私たちが考えることをやめない限り、大学や学問、そして哲学も、なくならないのだと思います。

根元の方から考える習慣をつけると、世界の見方が大きく変わる

5人の哲学者の視点を借りながら、皆さんの疑問を掘り下げてみました。

哲学というのは、どこまでも自分で問い、考える試みです。もし皆さんに有益な部分があるとすれば、むしろ考えるプロセスそのものだと思います。木の幹や根元の部分から考える習慣をつけると、視野が大きく開けるのは、間違いありません。日常のささいな出来事、現在の専門領域、将来のキャリア形成、小説や哲学書を読む行為まで、自ら考えながら行ってみると、全く違う世界が広がるでしょう。すぐに答えを出そうとせず、さまざまな角度から冷静に見つめること。そして大学にいるという環境を生かし、たっぷりと物事を考えてみてください。古今東西の哲学者たちは、あなたに寄り添い、ヒントを示してくれるはずです。

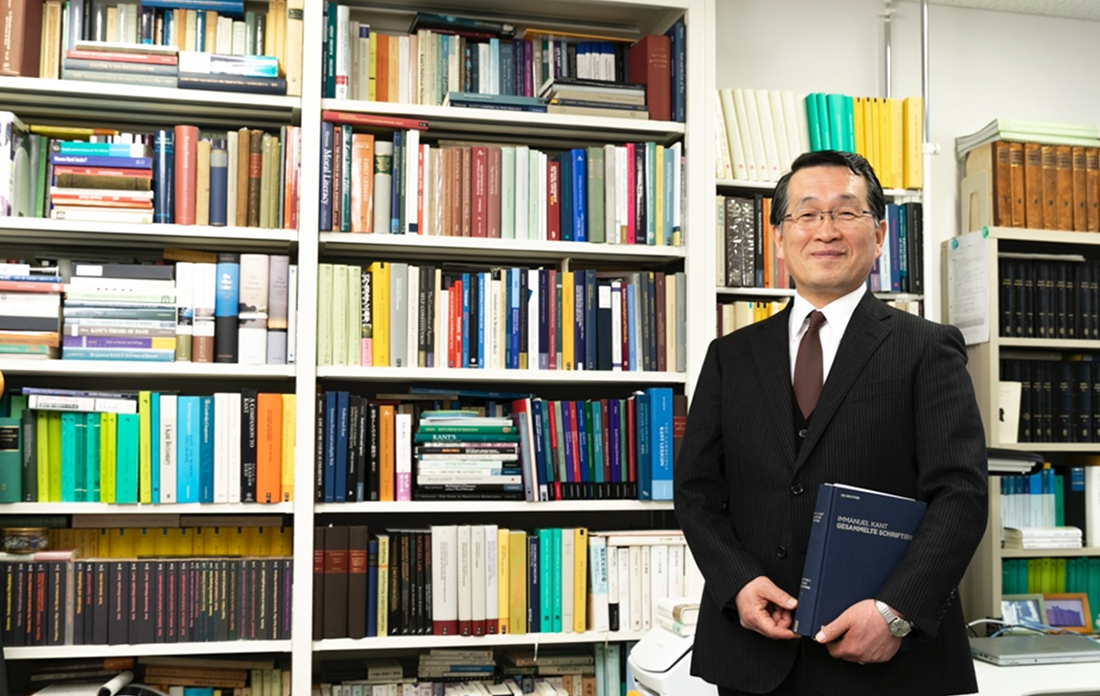

相澤 優太(2010年第一文学部卒)

撮影

小泉 賢一郎(2000年政治経済学部卒)

イラスト

前田 はんきち

編集

株式会社KWC

デザイン・コーディング

株式会社shiftkey

皆さん、哲学の世界へようこそ。難しいイメージが付きまとう哲学を避ける学生も多いのでは? その原因は、高校で倫理や世界史を“暗記”させられるからでしょうか。高校までは「誰が何を言ったか」にばかり目を向けますが、本来の哲学は「自分が何を問うか」が最も大事。当たり前のように思えるテーマに向かって、あえて自分で正面から問いをぶつける営みです。だから実は考えるだけで誰もが取り組める、自由度の高い学問なんですね。

これから早大生から寄せられた5つの疑問を紹介します。皆さん鋭い問いを立てており、それだけで十分に哲学に値します。今回は素朴な疑問を哲学者の考察から掘り下げていくわけですが、一般的なお悩み相談と比べると、「明快な解決策を提示していないじゃないか!」と感じるかもしれません。しかし、その答えのないところに、哲学の面白さがあるのです。では早速、ひもといていきましょう。