We are excited to announce that the Chair of the State of Qatar for Islamic Area Studies at Waseda University will be organizing the Majlis@Waseda on Dec.5, 2025.

We would like to share with you some important details about the event:

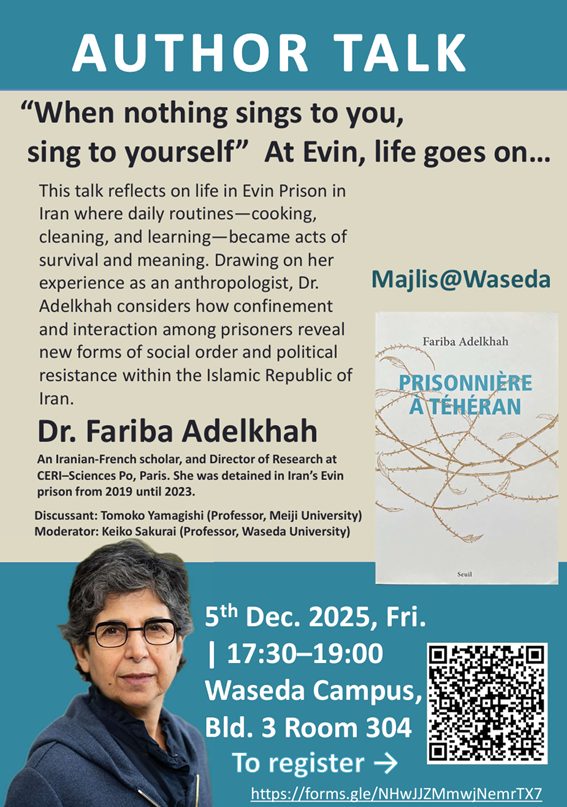

Author Talk “When nothing sings to you, sing to yourself” At Evin, life goes on…

Dr. Fariba Adelkhah

Director of Research at CERI–Sciences Po, Paris.

December 5, 17:30-19:00 (Friday)

Waseda University Building 3, Room 304

In this Majlis, renowned anthropologist Dr. Fariba Adelkhah will talk about her recent book Prisonnière à Téhéran: Une ethnologue détenue dans les geôles iraniennes (Prisoner in Tehran: An Anthropologist Detained in Iran’s Prisons).

In the book, she reflects on and documents her years (2019–2023) spent in Evin Prison in Tehran, offering an intimate anthropological perspective on life behind bars.

Below is the talk description provided by the author.

Let’s be prosaic, or if you prefer, down to earth! When there is fight for survival, it’s a good sign. It means life goes on, even if it is in prison. Fighting against boredom is part of it and, well, my life as a prisoner — for I can only speak for myself, or rather I no longer dare to speak for others — is full of signs that pay homage, as the subtitle of this text announces, to Kiarostami. It is, so to speak, a hymn to life.

Faced with the wait, the fate of any convict, the most difficult thing for a prisoner to face is undoubtedly to untangle why she is in detention and to manage the daily routine. Cut off from everything, knowing that she is now dependent on many people, in confinement — her family for financing her needs and for news about both her private life and her legal fate, the prison staff, who hold in their hands the material management of the inmates, and finally her fellow inmates with whom, henceforth, she has to share her days. In this situation, confusion is the norm, given the violent conflicts that constantly erupt, not only between the inmates, but also between them and the prison staff, not to mention the conflicts with the family, often on the telephone or on the day of the weekly visit. In reality, we all “crack up ” at one time or another, and this is probably also why we make sure that our lives as inmates are very busy, between cooking, sports, reading, training workshops, not to mention hygiene and cleanliness, the number one concern of the inmates. We train ourselves and some of us train the others in sports sessions or in learning a language. We all try to have objects or handmade products to give to the family once a month, on the day when this material transfer is authorized by the prison administration.

The fact that I have been denied my freedom, friends, loved ones, and of course my job, I was tempted to transform my everyday life as if it were a fieldwork, and I would like to talk about this life in prison. Discussing the jail in this manner involves dealing with the Evin’s history, which has undergone constant changes before and after the Revolution. But as an anthropologist what I am interested in is to talk about the life inside the jail, and the interactions between prisoners behind the walls. To what extent does confinement and technique of enquiry contribute to changes in terms of reproduction or transformation of social order? How do the prisoners help us to understand political resistance in Islamic Republic of Iran.

Please pre-register if you wish to attend at: https://forms.gle/NHwJJZMmwjNemrTX7