- News

- Event Report: “The Sound of Sight: Vision and Dissonance in Japanese Futurist Poetry” by Dr. Kevin Michael Smith

Event Report: “The Sound of Sight: Vision and Dissonance in Japanese Futurist Poetry” by Dr. Kevin Michael Smith

- Posted

- Thu, 20 Oct 2022

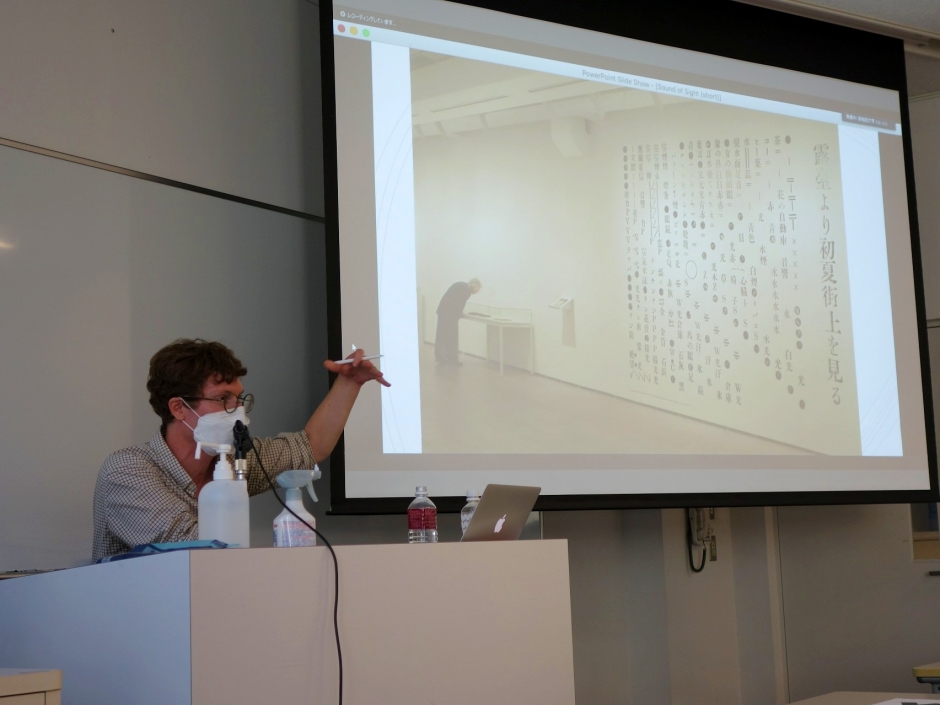

On July 22, 2022, Dr.Kevin Michael Smith (University of California, Berkeley) gave a lecture at Waseda University’s Toyama Campus. The lecture focused on the poems of Kambara Tai (1899-1997), Hirato Renkichi (1893-1922), and Hagiwara Kyojiro (1899-1938), and examined how urban noise is expressed in their poetry through synesthesia between the visual and auditory senses. This lecture was organized by Professor Toba Koji (Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences) and was held simultaneously in person and via Zoom.

Smith is visiting Waseda University as a research fellow. He is a specialist in modern Korean literature and culture who studies poetry and poetics in colonial Korea; he received his PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Davis in 2019 and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at UC Berkeley. Smith will soon publish his first monograph, Shuddering Century: Modernist Poetry in Colonial Korea and the Poetics of Historical Difference. The book includes a study of how colonial Korean poetry in the 1920s and 1930s was influenced by European and Japanese avant-garde art.

Smith is visiting Waseda University as a research fellow. He is a specialist in modern Korean literature and culture who studies poetry and poetics in colonial Korea; he received his PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Davis in 2019 and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at UC Berkeley. Smith will soon publish his first monograph, Shuddering Century: Modernist Poetry in Colonial Korea and the Poetics of Historical Difference. The book includes a study of how colonial Korean poetry in the 1920s and 1930s was influenced by European and Japanese avant-garde art.

Futurism, which emerged in Italy at the beginning of the 20th century, was a movement to incorporate into art the new perspectives brought about by rapid modernization and the development of mechanical civilization. Its mediums of expression ranged from poetry to painting, photography, architecture, and music. Smith showed paintings by representative Futurist artists such as Umberto Boccioni’s The City Rises (1910), and Carlo Carra’s The Cyclist (1913) on the screen, while introducing the dynamic urban landscape and sense of speed that the Futurists sought to express. He began his lecture by explaining the historical background behind the Futurist movement such as the development of industrial capitalism and rapid mechanization and urbanization.

This trend originated in The Futurist Manifesto published by Italian poet Filippo Marinetti in the French magazine Le Figaro in 1909, and was introduced to Japan almost simultaneously by Mori Ogai in his translation of the same text in the magazine Subaru three months later. However, the Futurist movement did not flourish in Japan until the late Taisho period, or the 1920s, when urban culture underwent a dramatic development. Smith’s research includes books such as Kambara Tai’s Futurism: A Study (1924) and The Starting Shot of the New Art (1926), as well as the activities in Japan of Russian Futurist painter David Burliuk, who came to Japan in 1920, and his joint work with Kinoshita Shiu, WAS IST DER FUTURISMUS -ANTWORT– (1923), and the leaflet MOUVEMENT FUTURISTE JAPONAIS distributed by Renkichi Hirato in front of Hibiya Park in 1921. Smith also introduced the following passage from MOUVEMENT FUTURISTE JAPONAIS:

“Libraries, museums, and academies are worth less than the sound of a car running down the street. Try smelling the repulsive odor of a library, and you will find that the freshness of a gasoline is many times greater than this.”

The description of the smell of gasoline as “fresh” in conjunction with the speedy sensory depiction of automobiles on the road suggests surprise at the new urban civilization they came to witness in the 1920s. Among the above-mentioned Futurist movements, poetry in particular attempted to dynamically recreate the intense and brand-new modern experience of the city through the visual effects of the arrangement of words on the paper. As specific techniques of expression, the Futurist poets used what they called “words in liberty,” including extensive use of onomatopoeia and the dispersed arrangement of type. Smith noted that these poems repeatedly describe urban noise, and that this synesthetic sound is a particularly important component of Futurist poetry.

Smith then referred to the concept of “soundscape” – “sound” as landscape – used by Saito Kei in his Listening to 1933: Soundscapes of Prewar Japan (2017), and suggested that we should pay more attention to the urban soundscapes depicted in the poetry of the Futurists, whose novelty of visual expression has been traditionally focused on in criticism. As specific examples, Smith introduced poems such as Ensemble (1931), published after Hirato Renkichi ‘s death, and Early Summer City View from the Balcony from Hagiwara Kyojiro’s poetry collection Death Sentence (1925), along with his own English translation. These futurist poems create a visual image of the city as if from a bird’s-eye view from an airplane or a high-rise building by sprinkling various vocabulary, onomatopoeia, and special symbols that symbolize the new urban culture and machine civilization throughout the paper. What differentiates these poems from other visual media such as photographs and paintings, however, is that the images are created by language with both sound and semantic content. In this respect, Futurist poetry has the synesthetic function of simultaneously evoking the sound associated with the words along with the visual image.

*The above image of Hagiwara Kyojiro’s poem Early Summer City View from the Balcony was excerpted from his poetry collection Death Sentence (1925, choryushashoten) and edited.

Smith concluded the lecture with a detailed analysis of Hagiwara Kyojiro ‘s poem, Early Summer City View from the Balcony (see photo above, excerpted and edited from Death Sentence). Looking down from the high balcony, the overall image of Tokyo, a modern city under reconstruction after the Great Kanto Earthquake, and the ground-level soundscape of individual words and onomatopoeia were jostling with each other. Smith referred to William O. Gardner’s work on modernism and modernity in 1920s Japan, Advertising Tower, and pointed out that Hagiwara’s political orientation toward anarchism is discussed therein.

The lecture was followed by a Q&A session. Questions from various perspectives were asked one after another. What functions did the characteristics of the Japanese language, with its various readings of a single kanji character and the use of katakana, play in Futurist poetry? What was the difference between the Japanese Futurists and the Italian Futurists, who defended Fascism? What kind of critique can be made of the misogynistic elements in Futurist aesthetics? The lecture completed successfully after the discussion for about an hour and a half.

Event details

- Date: July 22, 2022

- Time: 15:00 – 17:00 (JST)

- Venue: Waseda University, Toyama Campus, Building 32, Classroom 128

- Lecturer: Dr. Kevin Michael Smith

- Language: English

- Free of charge

- Open to the public through Zoom

- Tags

- Event Reports