- Featured Article

Who paid for your tuition? Letters from a father to his son

What a recent donation reveals about the experiences and opinions of a parent bearing the cost of university

Fri 24 Mar 23

What a recent donation reveals about the experiences and opinions of a parent bearing the cost of university

Fri 24 Mar 23

In 2021, the Waseda University History Museum received a donation of 232 documents, 227 of which pertain to education professor Yoshio Jinnouchi. Of these documents, 180 are letters from his father, Tazō Jinnouchi. The letters date from March 27, 1926, when Yoshio completed his entrance exams, to the summer of 1941, when he left for his second military deployment.

Tazō lived in Isahaya City, Nagasaki Prefecture while his son was a student. According to the documents, his income consisted mainly of earnings from small property rentals, work at a group purchase association and a cocoon sales cooperative association, in addition to contract work at the city’s arable land cooperative. He also held a municipal appointment in 1927.

His son, Yoshio, was born in Isahaya City in 1906. After graduating from Omura Municipal Junior High School, he entered the Waseda University Senior High School in 1926 and graduated from the Waseda University School of Literature in 1931. He left for China shortly after graduation, where he studied for approximately six months before joining the military. He began working at the Waseda University Student Office in February 1933 and became a teacher at the Senior High School in 1941, before being appointed assistant professor at the Waseda University School of Education in 1949.

MEMORIAL ALBUM OF WASEDA UNIVERSITY (1931), 2005年度外岡明氏寄贈外岡茂十郎関係資料 590, in the private collection of Waseda University History Museum

“Now that we are nearing graduation, it was worth the thousands of yen in tuition fees to finally see you graduate.”

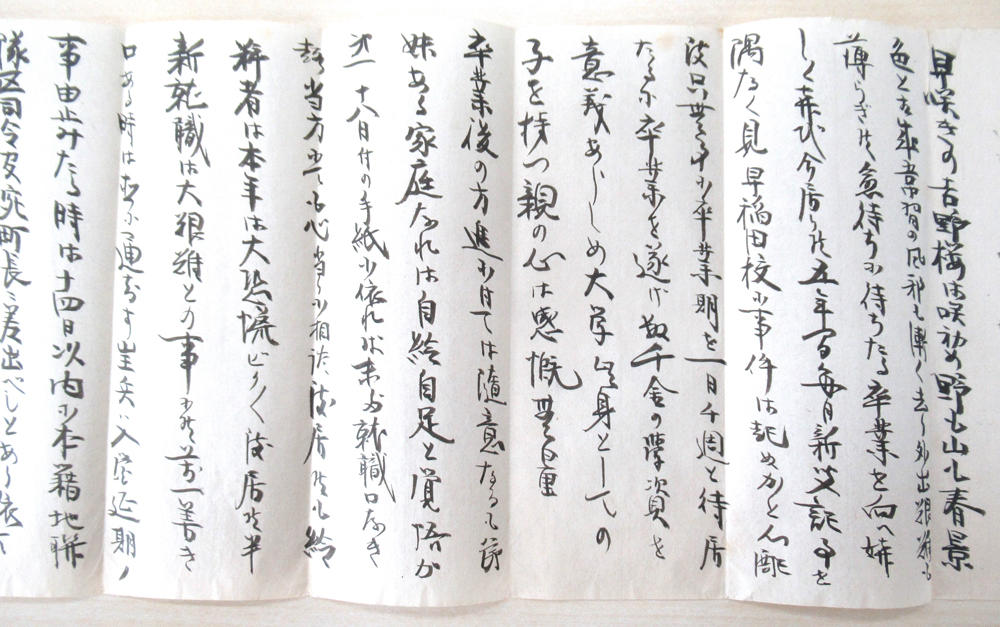

What did Tazō write in his letters to his son? In a letter dated right before Yoshio’s graduation, he wrote:

We’re all filled with joy to celebrate your long-awaited graduation! For the past five years, we’ve perused the newspaper daily, watching out for any incidents at Waseda and hoping for an uneventful graduation. Now that we’re nearing graduation, it was worth the thousands of yen in tuition fees to finally see you graduate. Words cannot describe how I’m feeling right now; I’m deeply moved to be a parent of a university graduate! (March 23, 1931)

Tazō’s congratulatory letter to his son (March 23, 1931)

The excerpt conveys Tazō’s overwhelming emotion evoked by Yoshio’s graduation. To Tazō, his son’s graduation meant more than obtaining a university diploma – it also meant release from his financial obligations. From FY 1926 to 1930, when Yoshio was a student, the tuition at the Waseda University Senior High School was 120 yen per year, and 140 yen per year for the undergraduate School of Literature. This calculates to roughly 10 to 12 yen a month, excluding the cost of uniforms and hats. Despite a reduced quality of life for himself, Tazō continued to send money to his son, saying that “tuition could be paid by cutting back on other expenses.” (September 28, 1927).

The letters reveal not only the financial details of Tazō’s payments, but also the challenges the family faced in managing their household and budget. The financial assistance also provided an opportunity for Tazō to periodically give career advice to his son.

“I pay for your studies by the sweat of my brow.”

As the economy faltered, so did Tazō’s motivation to continue sending payments for school expenses. In a letter dated March 27, 1927, he generously offered financial assistance to Yoshio, writing, “I will continue to send you money for tuition, as long as it’s not spent wastefully.” Just a few days later, on April 2, he wrote another letter to Yoshio, telling him to “save as much as possible on expenses,” as “these days, my expenses exceed my income. Mitsuko is also starting school on April 1.”

At times, his motivation declined sharply. Between April and May of 1929, the start of his son’s fourth year at university, he sent payments of 75 yen, 50 yen, and 50 yen to Yoshio, totaling 175 yen. Without delay, he received a reminder from the university to pay the remaining balance of 52 yen. Five days later, he prepared a money order made payable to the university and sent it to Yoshio, only to immediately receive a letter from Yoshio asking for 70 yen. In response, Tazō wrote:

I’m almost 60 years old with an income of just 50 yen per month. This 50 yen is the salary I receive for going to work at the arable land cooperative every day with my lunch box hanging from my waist, despite my position. I pay for your studies by the sweat of my brow… If this situation persists, I may even need to sell the land I inherited from my parents, and that would be heartbreaking. That’s why I would like you to plan to help this old father by doing some part-time work in Tokyo this year…On second thought, it may not have been wise for middle-class people like us to go to university. When you’re out in the world, you see that academics alone is insufficient to achieve success. In fact, I believe that common sense is the most important quality in order for one to do well in life, and I’d like you to think about that carefully. (June 26, 1929)

Tazō’s letter describing his struggles (June 26, 1929)

The remaining documents show decreased payments after that letter. A letter from January 1930 may shed some light on why they may have decreased. “Please don’t hesitate to tell me if you need money,” Tazō wrote in the letter, “I will send it to you if it’s absolutely necessary.” Perhaps Tazō’s strict guidance made Yoshio to re-evaluate and make necessary changes to his lifestyle.

“Think deeply about the hard work you and I poured into this, and what it would mean for it all to be taken away.”

In a letter cited earlier in the piece, Tazō wrote that he was often “watching out for any incidents at Waseda,” but there indeed was an incident just six months before Yoshio’s graduation.

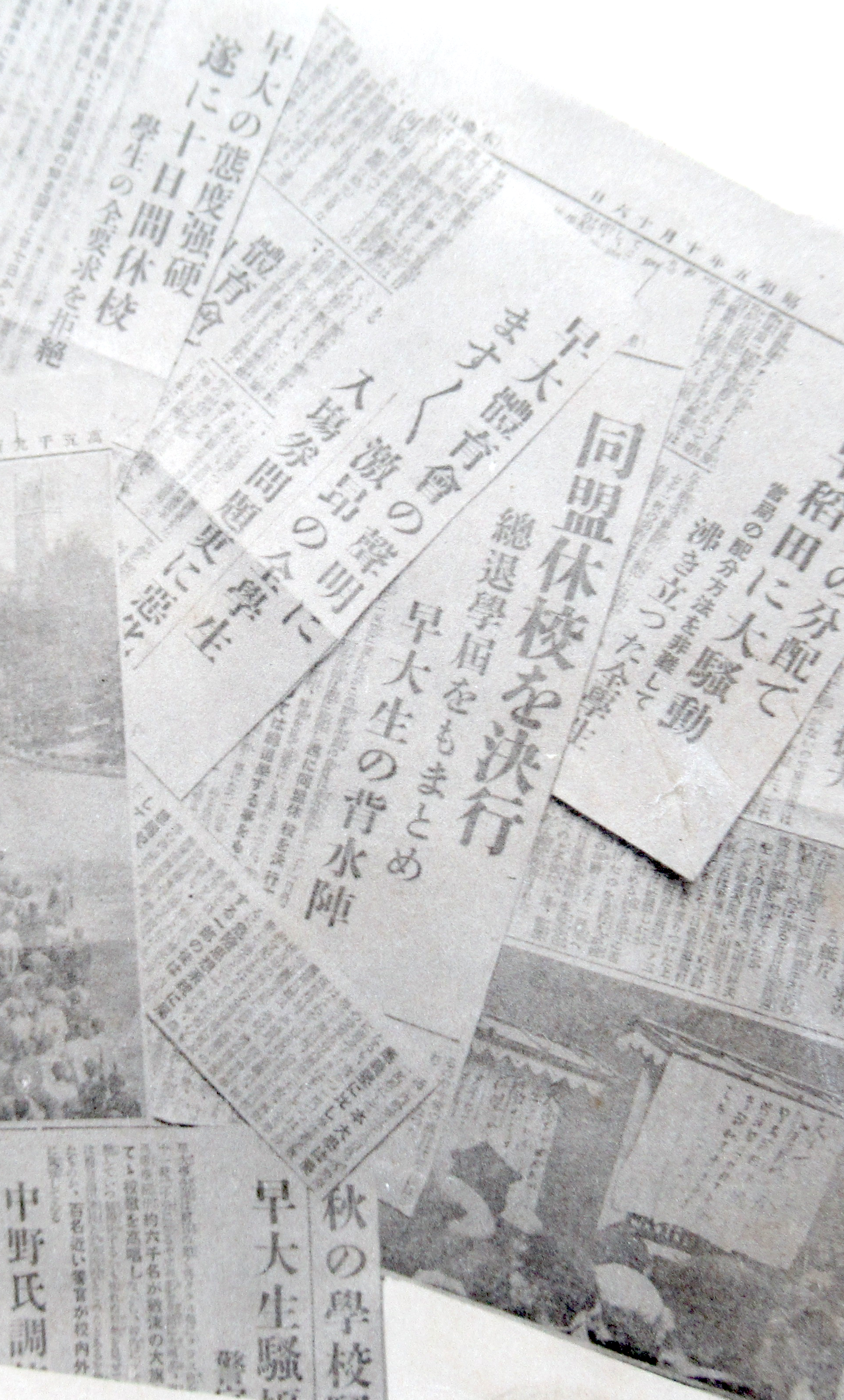

In October 1930, the Tokyo Baseball League held its opening match at Waseda University. A riot broke out due to problems with the distribution of Waseda-Keio game’s tickets, leading to the October 21 students’ boycott classes at Waseda. Growing concerned at the headline “13,000 Waseda Students Boycott Classes,” he sent a letter to Yoshio about what he read. “I trust your judgment and know that you would never do anything so thoughtless,” he wrote, “but as a parent, I cannot help but worry that you’ll somehow get caught up in such incidents,” describing what he knew about the situation surrounding the incident.

I’m not concerned about others, but we working-class citizens pour our heart and soul into paying our tuition fees. Now that in four or five months, you’ll reach the highest honor of your lifetime, even an old man like me is looking forward to the thought of you graduating, whether I’m asleep or awake. So never, ever join in any rash moves. I’m praying that you’ll lead your friends in the right direction for our nation, earn the respect of those around you, and receive a proper diploma. The underclassmen who are still far from graduation can afford to recover from any problems that may occur, but for the seniors who are on the verge of graduation, it only takes one mistake to instantly upend their progress. There are many unfortunate people who have to live with that mistake for the rest of their lives. Think deeply about the hard work that both you and I poured into this, and what it would mean for it all to be taken away. (October 25, 1930)

Newspaper headlines about the Waseda student boycott (from the 1931 yearbook)

This is the only instance in the letter collection where Tazō makes any mention of Yoshio’s life in the city and university, or his studies. It is evident that he placed a high level of trust in his son, and that even such a trusting father could not brush off the worry that his son could jeopardize his graduation through involvement in such incidents.

The Waseda University History Museum holds important historical documents encompassing the past, present and future of the university. We are able to share the Jinnouchi family letters with you today because of a succession of historical encounters: Yoshio, who kept his father’s letters with such great care; our donor who acquired and preserved them when they were no longer in Yoshio’s hands; and our museum which is supported by such generous donors. Please visit the museum to witness the results of such historical encounters in person.

- RELATED ARTICLES

-

-

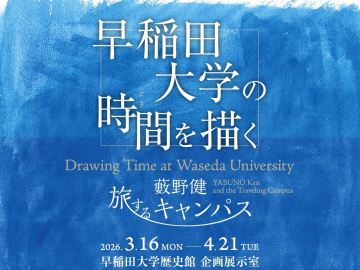

早稲田大学の時間を描く 藪野健 旅するキャンパス

早稲田大学の時間(とき)を描く 藪野健 旅するキャンパス 風景を旅し、時間(とき)を描く ―藪野健が見つめてきた早稲田大学のキャンパス。 藪野健は、身近な風景に向き合い、そこに刻まれた時間を丹念に描き続けてきた画家です。 […]

Fri 06 Mar 2026

-

The Honbu Documents Collection Recataloged into High‑Def, Now Featuring Over 150x More Records

February 3, 2026, the Waseda University History Museum added fine‑grained records for its “Honbu Documents” co […]

Fri 20 Feb 2026

-

2025 Spring Vacation: Info on the Opening Hours of Campus Offices, Facilities, Libraries, and More

Spring vacation will begin on Wednesday, February 4th and continue until Tuesday, March 31, 2026. Please note […]

Tue 27 Jan 2026

-

This piece was edited and modified by Tomonori Sano of the archives division of the Waseda University History Museum, from the original article by Yasuko Okado titled “Over 60 Letters That JINNOUCHI Yoshio Received from His Father While He Was a Student at Waseda University (1926-1931),” Transactions of Waseda University Archives, Vol. 53 (February 2022) with the permission of the author. The list of Jinnouchi family letters discussed in this piece will be shared on the Cultural Resources Database later.