What I Talk About When I Talk About Translating the Literature of Murakami Haruki

2021.10.07

- Lin Shaohua

In conjunction with the opening of The Haruki Murakami Library at Waseda University, a series of essays was commissioned entitled Encountering Haruki Murakami. These essays will allow people involved in various ways with Murakami to talk about their encounters and connections with his works and his world.

The first in the series is this essay by Lin Shaohua, Murakami’s principal translator into Chinese. As mentioned in his essay, the sheer number of people who have encountered Murakami’s work in Chinese through his translations is staggering—in fact, it represents the biggest non-Japanese community of Murakami readers. Indeed, it’s a community of which I am also a member, as I read my first Murakami work in 2002: Professor Lin’s translation of Norwegian Wood. I walked with Watanabe and Naoko through Yotsuya and Komagome, spent an early autumn afternoon drinking beer with Midori, discussed literature with Nagasawa in the Wakeijuku dormitory…these images and incidents swelled in my imagination, and from that moment on, I became a devoted Murakami fan. It has been almost twenty years now since then, but I still remember how I felt then as if it were yesterday.

So, without further ado, let’s hear what Professor Lin has to say about his process and experiences translating Murakami!

Quan Hui (Editorial Director, Waseda International House of Literature)

What I Talk About When I Talk About Translating Murakami

林少華/ Lin Shaohua

It might sound like a boast, but I swear it’s no lie: I am considered the world’s preeminent translator of Haruki Murakami. “Preeminent,” of course, does not indicate the extraordinary quality or excellence of my translations themselves—rather, it indicates the fact that it is through my translations that the most people in the world who do not read Japanese read Murakami. To be more specific, the forty-four Murakami books I’ve translated number about thirteen million five hundred thousand copies printed as of December 2020; based on a statistic I read somewhere that each published copy of a book ends up read by an average of four people, that would mean that over 54 million Chinese people have read Murakami in my translation. This is a number to rival that of any other author whose work is translated from Japanese—or from any other non-Chinese language, for that matter. There are many things I might want to talk about relating to this, but for now, I’d like to share a few things that come to mind when I think about translation itself.

1.

First of all, I am not actually a professional translator. I am a faculty member at a university, and my primary focus is the comparative study of Japanese and Chinese classical poetry. One day, a senior colleague in Beijing who specializes in modern Japanese literature approached me and said, “Would you be interested in translating Murakami’s Norwegian Wood? I think the style would suit you.” They were rather insistent, so I decided to give it a shot. In this sense, my encounter with Murakami’s work was a bit of a coincidence, or even pure chance—but as it turned out, it was also destiny.

The fact is, I’ve now translated many other Japanese authors, including Natsume Sōseki, Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, Kawabata Yasunari, Mishima Yukio and so on, but the author whose style suits me most is definitely Murakami. I frequently feel as though there’s a secret, personal tunnel linking me directly to him through his prose; elements in his work call out to me emotionally and resonate deep within me. In other words, I feel as though as a translator, I am part of a trinity with the reader and the original text, all of us breathing the same air.

I’m sure there are many people who would be able to convey the stories told in Murakami’s works perfectly well, but, if I may say so myself, I do not think there are many who would be able to translate his style like I can. Indeed, the Shanghai Translation Publishing House that puts out his works seems to recognize this subtle distinction, and they have entrusted all his works to me; readers, too, seem to respond well to my work and follow it diligently. It fills me with so much satisfaction and happiness. I’d like to thank Murakami’s literature for providing such an opportunity to me. It’s so wonderful that this literature exists in the world, and that the work of translation exists. This is the first thing I’d like to say here regarding my translations of the works of Murakami Haruki.

2.

I’m frequently asked in interviews and by readers via letters or the internet why Murakami’s literature is such a hit in China. I think there are three main reasons for this. The first is that the stories themselves are fresh and interesting. The second is that there’s a subtle intimacy about his work that is able to touch and resonate deeply within a reader’s heart. And third, I think his style is unique, possessing a singular, penetrating power. Murakami is an author exceptionally preoccupied with style, even going so far as to outright say that, to him, “style is everything.” And indeed, for me as a translator, the main reason I’ve devoted myself this much to his work is due to how taken I am with his style.

If I were to itemize his style’s distinctive characteristics, they would be 1) a simplicity that contains hidden depths (refinement); 2) an intellectual, yet delicate, wit (humor); 3) a restrained sense of lyricism (romance); and 4) a crisp, clear rhythm (beat). Of these, it’s the rhythm that seems most important. Among the Japanese authors I’ve read, I recall no one—except perhaps Natsume Sōseki—who can rival Murakami’s mastery of rhythm. Therefore, one of the main tests for a translator is to convey the flavor of such prose, its depth and its rhythm, using appropriately simple language.

There may well be those who have doubts about my suitability for such a task, thinking, “How can you, a specialist in classical literature, grasp Murakami’s modern sense of rhythm, which he learned from jazz?” And it’s true, I don’t know much about jazz. But as I said before, I am a specialist in ancient poetry, and I’d like to think I’ve internalized its qualities to a certain extent. As you surely know, without rhythm, there would be no classical Chinese poetry or Japanese waka. Indeed, you could say that Japanese waka and especially classical Chinese poetry are forms of literature that have reached the very apex of simplicity—of refinement. I don’t think I’m boasting this time when I say that just as Murakami learned rhythm from jazz, I’ve somehow managed to learn it from classical Chinese poetry and been able to apply this skill to the translation of Murakami’s literature. And it’s not just its rhythm, or “beat.” It’s the other qualities of his language as well—its luster, its undulating surfaces, its flow, its breath, its verve—that I strive to convey in the most natural, un-“translated”-feeling Chinese I can. This is my preoccupation as a translator, and the reason why I continue to do this work.

3.

As stated above, reproducing style in translation is of utmost importance. But this is not translation’s only purpose. The essence of literary translation lies in the recreation of an aesthetic world, a reconstruction of the aesthetic feeling induced by the original. An excessive, bureaucratic display of fidelity to surface meaning and exact phrasing becomes less important in this sense than bringing out the original’s flavor, its mood and warmth and nuance—in other words, the heart and soul imbued by its creator. The translator must find the exact wording that will make Chinese readers experience the same aesthetic feelings in the same magnitude as those experienced by Japanese readers of the original.

For this reason, there are times when a tightly focused worldview or a personal attachment or absurd love becomes necessary in the process of translating. In fact, without these things, the translator cannot convey the proper aesthetic feeling. It doesn’t matter how linguistically or grammatically perfect it is, a translation devoid of aesthetic feelings is dead, which results in the death of the literature itself. Does there exist in the world any literature that is merely “correct” without conveying feeling? I don’t know about the state of translation in Japan, but in China, there are many translations that at first glance appear perfectly faithful, neutral, balanced, even mechanical. And it is these kinds of translations that feel like a meticulously painted dragon without its eyes filled in—translations that move no one. If I may say so myself, this is the effect I want to avoid at all costs in my process of translation. That is my modest aim.

4.

For this reason, I cannot say that my translations are the most standard. Though I also think there is no such thing as a truly “standard” translation. No matter how superlative or renowned a translation might be, it can never completely recreate Murakami’s literature in some sort of standardized, exact sense. It also goes without saying that translation is not the same as self-expression, and in principle, it’s true that translators must strive to shed or even extinguish their selves in order to absorb as much of the original’s inherent flavor as possible. But the problem remains that no matter how much translators might attempt to shed or extinguish themselves, there is always a part of them that stubbornly persists, that can never be truly eradicated, and this stubborn remainder suffuses the translation with the translator’s odor, or, you might say, “bias.” In other words, this thing called the self (the ego) will always manage to peek through. To use Murakami’s own words on the matter (not that I mean to use his thoughts on translation to justify my own conduct!), an excellent translation is always “suffused with a love full of personal prejudice.” To put it in extreme terms, one hundred translators would produce one hundred distinct Murakamis, and therefore one hundred distinct Murakami literatures.

I have, in fact, examined many other translations of Murakami into Chinese by people both in mainland China and outside, and while the stories of course remain the same, as does the general sense, it’s the style—particularly the rhythm—that varies most widely among them. Which is not to say that my version is the standard and that all others fall short! In fact, this sort of variance is the most natural thing in the world. Literary translation is the result of a fusion between the style of the original and that of the translator. This is the limit of the work of translation, but also its appeal, its pleasure. I’ve heard that some have criticized my translations as possessing too beautiful a style, but all I can say is that I strive to translate beautifully what I find beautiful and translate roughly what I find rough. I also have the impulse to add that if Chinese readers find my translations beautiful and a pleasure to read, what’s really the harm in that? But of course, I can’t really say that.

5.

The Murakami novel I found the most difficult to translate so far was The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Even just finding the right Chinese for “Nomonhan” took almost a whole day’s work. It took a full year to translate all three volumes of it, and it was a struggle the whole time. But at the same time, it was the most absorbing novel I’ve translated, one that left a very deep impression on me. The book contains Murakami’s intensely felt viewpoints on recent Asian history, told with courage and stoic grace, interrogating the fundamental nature of certain forms of violence, especially state-sponsored violence. It also has a reflexive quality to it, displaying his anxieties about the present and future of Japan in the manner of a Japanese intellectual reckoning with his conscience, his sense of right and wrong. As I translated the novel, I felt my own heart being cleansed, while also feeling shaken to my very soul. At one point, I engaged in discussions on the theme of “Murakami Haruki and East Asia,” and from my point of view, this novel contains the most “Asian” parts of the Murakami oeuvre, displaying the clearest relationality between Murakami and the rest of Asia. If there’s an element that binds Murakami’s literature to the people of East Asia, I believe this is where it will be found. He is an important writer.

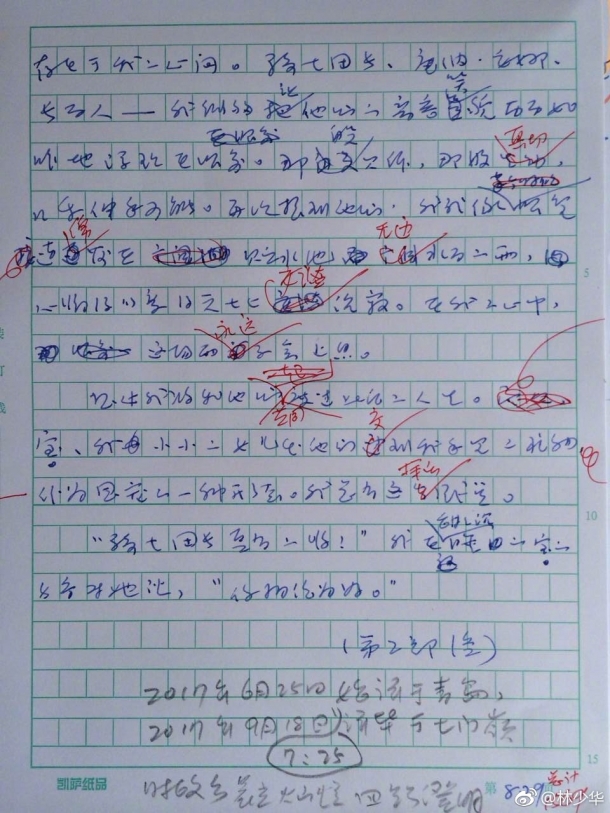

林先生の『騎士団長殺し』翻訳手稿

林先生の『騎士団長殺し』翻訳手稿

6.

My newest translation is the lengthy novel Killing Commendatore (my newest translation of a work that is not a novel is Haruki Murakami: A Long, Long Interview by Mieko Kawakami). “Newest,” of course, is relative—it’s already four years old. I began my translation of the original, which came out February 25, 2017, on June 25 of that year and finished it by September 18. If that seems fast, you’re right—it was pretty fast! Luckily, it coincided with summer vacation, so lectures had stopped, and I could return to my place in the country to isolate myself almost completely from the outside world and concentrate on the translation. During that time, my manuscript paper and my fountain pen were my “faithful companions” morning to night; the intensity of my concentration inevitably led me to overwork myself to the point that my right hand and arm began to hurt terribly. To be honest, I thought that if this book wasn’t interesting, it would surely be the death of me. That sounds like a joke, but it wasn’t. Happily, though, the book turned out to indeed be interesting, even fun, to translate.

The most fun parts, the parts that left the deepest impression on me, were naturally his style and rhetoric, especially his use of metaphor. I have it on hand, so I’ll share a few examples of what I mean.

Original Japanese:

割れた雲間からいくつか小さな星が見えた。星は散らばった氷のかけらのように見えた。何億年ものあいだ溶けることのない硬い氷だ。芯まで凍りついている。(「36 試合のルールについてぜんぜん語り合わないこと」)

My Chinese:

云隙间闪出几颗小星。星看上去像是迸溅的冰碴。多少亿年也没能融化的硬冰,已经冻到芯了。

English (Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen) :

I could see stars peeping from the cracks between the clouds. They looked like scattered crystals of ice. Hard crystals, millions of years old, never melting. Hard to their very core. (36: What I Want Is Not to Have to Discuss the Rules of the Game)

Original Japanese:

(彼は)ゆっくりと歩いて玄関にやってきた。そしてドアベルを押した。まるで詩人が大事なところに置く特別な言葉を選ぶときのように、慎重に時間をかけて。(「38 あれではとてもイルカにはなれない」)

My Chinese:

(他)缓缓移步走来门前,按响门铃,简直就像诗人写下用于关键位置的特殊字眼,慎重地、缓慢地。

English (Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen):

[He] walked slowly to the front door. Then he rang the doorbell. Slowly and deliberately, like a poet selecting the precise word for a crucial passage. (38: He Could Never Be a Dolphin)

Original Japanese:

彼女が微笑みを浮かべるのを目にしたのは、たぶんそのときが初めてだった。まるで厚い雲が割れて、一筋の陽光がそこからこぼれ、土地の選ばれた特別な区画を鮮やかに照らし出すような、そんな微笑みだった。(「33 目に見えないものと同じくらい、目に見えるものが好きだ」)

My Chinese:

目睹她面带笑容,这时大约是第一次。就好像厚厚的云层裂开了,一线阳光从那里流溢下来,把大地特选的区间照得一片灿烂——便是这样的微笑。

English (Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen):

I think it was the first time I’d seen her smile. It was as if a ray of sunlight had shot through a crack in an overcast sky to illuminate one special spot. It was that kind of smile. (33: I Like Things I Can See as Much as Things I Can’t)

Original Japanese:

若い叔母と姪の少女、年齢の違い、成熟の度合いの差こそあれ、どちらも美しい女性だった。私は彼女たちの姿を窓のカーテンの隙間から観察していた。二人が並ぶと、世界が少しだけ明るさを増したような気配があった。クリスマスと新年がいつも連れだってやってくるみたいに。(「59 死が二人を分かつまでは」)

My Chinese:

年轻的姑母和少女侄女。固然有年龄之差和成熟程度之别,但哪一位都是美丽的女性。我从窗帘空隙观察她们的风姿举止。两人并肩而行,感觉世界多少增加了亮色,好比圣诞节和新年总是联翩而至。

English (Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen):

They were so different in age and stage of maturity, this young aunt and her niece, yet both were so lovely. I observed their approach through the parted curtains. When they walked side by side, the world brightened a little. As when Christmas and New Year’s arrive in tandem each year. (from Chapter 59: Until Death Separated Us)

What do you think? Aren’t they so tasteful and elegant as expressions, perfectly suited metaphors to convey the reality of what they describe?

The American literary critic Harold Bloom once said, “I accept only three criteria for greatness in imaginative literature: aesthetic splendor, cognitive power, and wisdom.” I think the same criteria could be applied to this novel as well. In any case, as a translator, I find myself so keenly drawn to Murakami’s work, and I apply myself to the task of translating it with a sense of excitement.

Lastly, I have just one more thing I want to say. It’s rather embarrassing to admit at this point, but there was a time when I felt the burning need to try my hand at writing a novel, to create a Norwegian Wood of my own—let’s call it Qingdao Wood. And I actually did try several times to write one, but in the end, I had to admit that I was not born with the talent to be a novelist, and I gave it up. Still, though, I’ve felt somehow dissatisfied with the idea that I might live my entire life just as a translator, so lately I’ve been writing again, essays this time rather than fiction. And as I do, it has become obvious how very many things Murakami has taught me over the years. I would like to take this opportunity to thank him for that from the bottom of my heart.

This has been a self-indulgent talk, self-indulgently presented. I will end it here.

Early Summer, 2021

English excerpts from Killing Commendatore are taken from

Murakami Haruki, Killing Commendatore,

Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen, trans.

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018)

(Translated by One Transliteracy, LLC)

Profile

Lin Shaohua, whose ancestral home is Penglai in Shandong Province, was born in Changchun the province of Jilin and received his graduate degree from the Japanese Literature Department at Jilin University. After holding a position as Professor of Literature at Jinan University, he now works in the Foreign Languages Department at Ocean University of China in Qingdao.

He first visited Japan in 1988, spending a year as an exchange student in the graduate school of Osaka City University. He returned to Japan in 1993, working for three years as a foreign lecturer at the University of Nagasaki before receiving a Japan Foundation Fellowship in 2002 that allowed him to work at the University of Tokyo for a year. In 2018, he received the Japanese Foreign Minister’s Commendation.

His translated works number nearly a hundred titles, including Norwegian Wood, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, and Killing Commendatore by Haruki Murakami, as well as I Am a Cat by Natsume Sōseki, Rashomon by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata, and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima. His original works include The Beauty of Falling Blossoms, Homesickness and Intuition, A Light on a Rainy Night, Stranger, and many others.

One TransLiteracy, LLC, is a boutique translation and cultural consultation agency founded by Miyabi “Abbie” Yamamoto, Ph.D. We are a team of highly educated native or native-level bilingual and bicultural experts who provide meticulous translations with linguistic acuity, hone texts for precision and elegance, and provide concise explanations of cross-cultural exchange. The founder, Abbie, grew up in Tsukuba, Japan and received her Ph.D. in Japanese and Korean literatures at the University of California, Berkeley. She is passionate about promoting cross-cultural exchange and everyday practices of intentional inclusion.

*This article was made possible through the support of the Waseda International House of Literature and Top Global University Project in collaboration with Waseda University’s Global Japanese Studies.

Related

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Rebecca Brown

2025.12.02

-

“Letters from the Haruki Murakami Library”― Camilla Grudova

2025.10.20

-

Memories of Things That Never Happened to You

2022.12.12

- Hideo Furukawa

-

Historical Consciousness and “Boomerang” Thoughts in the Works of Haruki Murakami

2022.05.08

- Tetsurō Koyama

-

Useful Landscape

2022.03.28

- Ryō Mizuhara

-

My Personal History with the Literature of Haruki Murakami

2022.02.25

- Shōzō Fujii