TAKAO Saki, Assistant Professor

How I Became Interested in This Research

My field is experimental psychology, with a particular focus on visual perception and visual illusions. When I first encountered visual illusions as an elementary school student, I was struck by the realization that the world we see does not always match physical reality. At the same time, I was deeply fascinated by the aesthetic beauty that many illusions have. This experience became the starting point for my lifelong questions: why do we sometimes “misperceive” the world, and how does the brain construct a coherent and stable representation of it?

As a student, building on this early curiosity, I studied classical geometric illusions as a way to investigate contextual effects in vision. In the course of that work, I became increasingly aware that the world we inhabit is itself constantly changing in space and time. This led me to a broader question: in a spatiotemporally dynamic visual world, how does the brain construct what we experience as the “present”?

What I Study in Concrete Terms

When we look at the external world, light passes through the lens of the eye, forms an image on the retina, and is converted into electrical signals that are sent to the brain. However, the sequence of processing steps required for this information to be transformed into conscious perception takes on the order of several hundred milliseconds. This means that our perceptual world is always delayed by at least a few hundred milliseconds relative to the moment light hits the retina.

Despite this delay, we do not feel as though we are seeing the world late; instead, we experience it as smooth and seemingly real-time. My research approaches this problem from the idea that the brain may compensate for this delay by predicting the future.

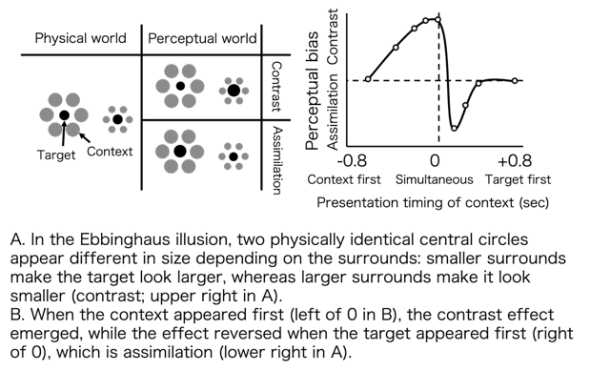

To investigate this, I conducted experiments using the Ebbinghaus illusion, a classic size illusion. In this illusion, a central circle (the target) appears smaller when it is surrounded by larger circles, and larger when surrounded by smaller circles (the inducers or contextual stimuli; left side of the figure). In my experiments, I systematically manipulated the relative timing of the target and the contextual circles to examine the temporal dynamics of the contextual effect. I found that when the context precedes the target, the typical illusion occurs. However, when the context is presented after the target, the effect reverses: targets surrounded by small circles appear larger, and those surrounded by large circles appear smaller (right side of the figure).

I named this phenomenon Prospective-Contrast Postdictive-Assimilation (PCPA) and proposed that it reflects a process in which the brain integrates information from both the past and the future along the time axis. My current work aims to clarify the psychological and neural processes underlying PCPA. To do this, I am planning experiments that measure the temporal dynamics of various visual features (such as size, brightness, and orientation), examine how PCPA relates across these features, and investigate the developmental trajectory of PCPA in infants.

What This Research Can Reveal

The research I am pursuing addresses a fundamental question in vision science: how does the brain construct the present and predict the future? If we can show that PCPA is a general phenomenon that appears across a wide range of visual processes grounded in predictive vision, this would imply that what we experience as “now” actually includes information from the near future.

This has significance not only as empirical evidence, but also as a theoretical contribution to vision research. The idea of predictive vision has a long history, yet we still lack detailed knowledge about the specific mental and neural computations that implement it. By quantitatively characterizing the mechanisms behind PCPA, I hope to advance our overall understanding of visual processing.

From an applied perspective, the findings of this research are also important. In fields such as VR/AR and robotics, system design increasingly needs to take into account delays and prediction in human perception. In everyday motor behavior, we must constantly track the positions of our limbs and objects in motion, which makes prediction-based perception essential in clinical contexts as well. The knowledge gained from this research has the potential to directly inform such applications.

Future Directions

Building on the findings obtained so far, I plan to examine PCPA in more detail by incorporating research methods that focus on individual differences and developmental changes. I also intend to conduct collaborative projects with researchers in Japan and abroad, using diverse methodologies to test PCPA from multiple angles and ultimately work toward a comprehensive model of visual perception.

Ultimately, my goal is to offer an empirical answer—grounded in experimental psychology—to the philosophically profound question of how humans experience the present. At the same time, through education, exhibitions, and science communication, I hope to share the fascination of visual illusions with a wide audience and to give back the outcomes of this basic research to society.