ESCANDE Jessy, Assistant Professor

Introduction

A bird’s-eye view of contemporary Japanese fantasy across various media reveals a striking pattern. While some globally recognized titles—such as Studio Ghibli’s animated films or the novels of Murakami Haruki—stand out as exceptional, they remain islands in an otherwise uniform sea. Many modern Japanese fantasy works are neomedievalist in style, heavily drawing from global cultural imaginaries and set against pseudomedieval backdrops inspired by European history.

No one would deny that Dragon Quest (in games) or That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime (in novels) are quintessentially Japanese. However, these works are not set in Eastern fantasy worlds. While they may occasionally incorporate East Asian motifs, their worldbuilding is fundamentally grounded in Western, particularly European medieval, archetypes. This trend began to take shape in the 1970s and expanded significantly during the 1980s. By the late 1980s, Western-style Japanese fantasy had begun to penetrate overseas markets less due to specific strategic export ambitions on Japan’s part but more due to the efforts of foreign distributors eager for new content.

At the time, the dominant assumption in Japan was that Japanese artists’ media, created for domestic audiences, would struggle to resonate internationally. This belief proved to be dramatically incorrect, as evidenced by the global surge in Japanese popular culture around the turn of the millennium. What was once dismissed as, at best, culturally insular or at worst, “otaku” (nerd)—a term often equated with obsessive fandom—became a key driver of Japan’s soft power.

Personal Context: From French Broadcasts to Academic Inquiry

I was one of the many Western viewers who were swept up in this cultural wave. Growing up in France, I encountered an array of Japanese animations through television programs such as Club Dorothée (1987–1997), which played a pivotal role in popularizing Japanese pop culture in France. This long-running, youth-oriented program introduced French audiences to iconic anime series such as Dragon Ball, Saint Seiya, and Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, laying the foundation for a generation of fans who would come to associate Japan with vibrant, fantastical storytelling.

Alongside these developments, Japanese video games—particularly role-playing games (RPGs)—gained a devoted following in France. However, a broader recognition of fantasy manga arrived somewhat later. While this essay cannot cover the full history of these cultural exchanges, it is worth noting that many anime series and most Japanese RPGs (now known as JRPGs) that reached France audiences were strongly oriented toward fantasy.

French audiences, accustomed to the dominance of dubbing, often did not immediately recognize these works as Japanese, especially because of their Western-themed settings. The same held true for fully localized video games. It was only as I grew older that I realized the media I had been so captivated by were of Japanese origin, despite their distinctly European aesthetic. This realization struck me as peculiar, as it contradicted the intuitive assumption that cultures naturally draw on their own traditions when imagining fantastical worlds.

The primarily Western orientation of fantasy in Japan raises a few eyebrows. It is widely accepted as a defining trait of the fantajī (ファンタジー; fantasy in katakana) genre, a transliteration that underscores its foreignness. Some works categorized as “fantasy” in the West would fall under various genres in Japan, such as gensō bungaku (幻想文学, “fantastic literature”) or kaiki shōsetsu (怪奇小説, “tales of the strange”). The epistemological distinctions between these categories can be debated, but the boundaries of the term fantajī do not fully align with those of its English counterpart. In Japan, fantajī is generally understood to be occidental and neomedievalist in nature, although exceptions and nuances certainly exist that could be explored in greater depth in scholarly discussions

However, this cultural phenomenon was surprisingly under-documented. I struggled to find clear explanations as to why an entire culture would so thoroughly bypass its own heritage—or even its regional cultural sphere—when imagining fantastical worlds and go out of its way to find inspiration in such distant cultures.

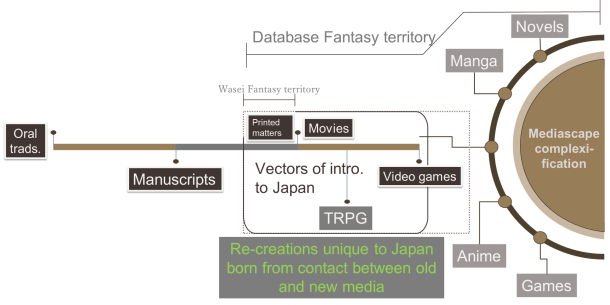

Database Fantasy and the Role of Cultural Brokers

This lack of answers eventually led me to pursue my doctoral research. At Osaka University’s Laboratory of Comparative Literature, I set out to clarify the historical and cultural ramifications of this phenomenon. My findings revealed that the conditions driving the emergence of contemporary Japanese fantasy can be traced to a specific cultural and technological paradigm: the Japan’s gaming culture in the 1980s and 1990s. From the reception of foreign tabletop RPGs and video games to the development of domestic titles to their transmedial circulation across Japan’s evolving mediascape—game media rooted in foreign cultural frameworks came to form the backbone of what I term the modern Japanese fantasy imaginary.

Central to this development is the concept I define as “database fantasy.” This refers to a substantial portion of contemporary Japanese fantasy, characterized by the extensive use of motifs, most of which are foreign in origin, that are drawn from overseas myths, religions, and sagas. These motifs underwent hybridization at different times during their passage to Japan, giving rise to distinctive, localized reinterpretations. Moreover, these motifs are not used in isolation but form part of a larger, internalized repertoire, a symbolic database, that creators draw from and audiences intuitively understand. (Jessy Escande, “Foreign Yet Familiar: J. L. Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings and Other Cultural Ferrymen in Japanese Fantasy Games,” Games and Culture 18, no. 1 (January 2023): 5)

Figure 1 A Few Examples of Database Fantasy Titles

From left to right:

1st line – That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime (Manga Vol. 1, Fuse & Mitz Vah, 2015); Final Fantasy VII (Square, 1997); Dragon Quest III (Chunsoft, 1988); Delicious in Dungeon (Vol. 1, Ryoko Kui, 2014).

2nd line – Record of Lodoss War (Animation, Madhouse, 1990–91); Goblin Slayer (Manga Vol. 1, Kōsuke Kurose, 2017); Monster Musume (Manga Vol. 1, Okayado, 2012).

Database fantasy is best understood as a meta-genre: rather than adhering to traditional genre-bound narrative structures, it emerges from the aggregation and recombination of modular motifs. These motifs, often sourced from geographically and historically distant cultures, are decontextualized, stripped of their original cultural meaning, and repurposed across various genres and media formats.

Throughout my doctoral research, I have developed a comprehensive, bird’s-eye perspective on database fantasy and its position within the modern Japanese mediascape. This work also emphasizes the need to carefully consider the role of games as cultural brokers and intermediaries in the transmission and transformation of cultural content.

Figure 2 Japanese Fantasies and Their Mediascape

Throughout my doctoral research and my current work at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study, I have pursued two interrelated goals: first, to document how foreign motifs were received and adapted in Japan, thereby shaping a culturally hybrid fantasy imaginary; and second, to examine why this genre has sustained its popularity. To address these aims, I adopt a two-pronged methodology, beginning with case studies.

Case Studies: From Golems to Lamia

The familiarity of many Japanese consumers—regardless of their level of genre literacy—with creatures such as golems, ghouls, and dullahans is striking. They can often describe these beings’ core traits, demonstrating an understanding of them as signs in the semiotic sense. However, they frequently lack knowledge of their cultural origins: the golem from Judaic folklore, the ghoul from pre-Islamic Arabian lore, and the dullahan from Irish tradition. Instead, these beings are commonly recognized as generic symbols of fantasy worlds.

Furthermore, in Japan, these motifs often acquire characteristics that diverge significantly from their original contexts, for example, golems as relics of lost civilizations, ghouls as generic undead monsters, and dullahans as knight-like figures. While some of these transformations stem from earlier Western reinterpretations, many are distinctively Japanese reinventions. Over time, such reimagining has led to culturally localized versions of originally foreign motifs. The accumulation of these motifs—many of which entered Japan through similar channels—contributes to an internalized database of fantasy elements that underpins database fantasy, an inherently transmedial phenomenon.

These transformations are not solely the work of abstract cultural forces. They are mediated by cultural brokers—translators, game designers, scenario writers, editors, and even fan communities—who mediate and reinterpret motifs across cultural boundaries. These actors play a central role in shaping how foreign elements are reimagined within the Japanese media ecosystem.

Game mechanics also play an important role in this process. Bestiaries, stat blocks, level-scaling systems, and enemy taxonomies abstract creatures from their narrative and spiritual contexts, reconfiguring them as manipulable and iterable content units. These units circulate not only within games but also across the broader mediascape. In this way, the codification of these motifs in game systems significantly influences how they are remembered, deployed, and hybridized in new works.

Unlike conventional genre structures, in which motifs are governed by genre-specific expectations (e.g., warriors and wizards battling evil in heroic fantasy), database fantasy functions as a motif repository. These motifs are continuously recontextualized across different genres. For example, the lamia—originally a half-woman, half-snake figure from Greek mythology—appears in Japanese fantasy as a monstrous adversary in heroic settings as well as as a romantic partner to a Japanese protagonist in fantastical reimaginings of modern-day Japan, such as in the jingai genre discussed elsewhere2.

Figure 3 Examples of the Lamia in Database Fantasy

Final Fantasy III, Square, 1990 In-game sprite (graphic element)

Monster Musume, Okayado, 2012- Cover

Despite the lamia’s cultural and geographic distance from Japan and the near-total absence of awareness of its mythological origins or its Romantic reinterpretation in Keats’s poetry, its core identity remains intelligible across disparate contexts.

Isekai and Sociocritical Fantasy

Examining fantasy motifs that are now internalized in Japanese fantasy and the cultural brokers responsible for their transmission and transformation helps us understand the historical development of Japanese fantasy. However, this alone does not fully account for the genre’s enduring popularity over the past several decades. This is where the second half of my research comes in——not only investigating how these fantasy imaginaries are built but also exploring how they are used.

The isekai genre offers a particularly compelling case. As a subgenre of database fantasy, isekai relies heavily on the previously discussed repository of motifs and symbols. This genre typically centers on a modern Japanese protagonist who is transported to another world—often one modeled loosely on medieval Europe. The fact that a Japanese character, rather than a native inhabitant of the portrayed fantasy world, serves as central to these stories is significant. These protagonists are frequently portrayed as socially marginalized within Japan: overworked salarymen, socially shunned otaku, bullied teenagers, or “NEETs” (Not in Education, Employment, or Training). Upon crossing into the new world—whether through reincarnation, summoning, or crossing some other threshold, the protagonist find the self-actualization that eluded them in Japan. Unlike the protagonists of classic Western portal fantasies, they rarely consider returning.

The subtext is clear: if a simple change in environment enables personal success, the problem lies not with the individual but with society. This narrative pattern, in which societal failure is externalized and transcended in a foreign world, resonates powerfully with audiences seeking vicarious liberation from structural pressures in Japan’s education and labor systems. When stripped of its increasingly derivative incarnations, the core of isekai reveals itself as a sharply sociolcritical narrative that leverages fantasy to highlight and critique specific shortcomings of contemporary society.

To Conclude

While isekai represents only one branch of Japanese fantasy, the broader phenomenon of database fantasy offers creators a distinctive advantage: they can draw from a vast reservoir of motifs without being bound by the cultural and historical contexts those motifs carry in their places of origin. This creative flexibility may be a key factor in the database fantasy’s remarkable longevity, especially in a pop culture landscape where most genre cycles tend to be short-lived.

My research—through ongoing case studies and critical engagement with the sociological implications of database fantasy’s culturally hybrid imaginary—aims to build on these foundations. This includes analyzing how the Western far right’s reception of Japanese fantasy suggests specific motifs with which these groups resonate and an ongoing exploration of creative practices by Japanese authors that might be interpreted as instances of cultural appropriation. By critically examining these dynamics, I hope to further develop the theoretical framework for understanding the global circulation of hybridized fantasy imaginaries.

In the near future, I also plan to develop a digital database to make this semiotic repository visible and accessible beyond individual works. This platform will serve as a collaborative resource for scholars, creators, and enthusiasts interested in exploring the broader, cross-media dimensions of Japanese fantasy. It will also lay the foundation for comprehensive, interdisciplinary investigations into the evolving landscape of Japanese fantasy worlds.