MATSUO Risa, Assistant Professor

I began my career as a musicologist and researcher of Western music, particularly Fryderyk Chopin (1810-49, Polish composer). However, during my doctoral studies at the University of Warsaw, I developed a strong interest in the composer’s relationship with poets and literary works. My doctoral thesis examined Chopin’s relationship with Polish poetics and explored the intentions of his Ballades (op. 23, 38, 47 and 52), while my current research has shifted its base to France, where Chopin spent the second half of his life, and is concerned with the communities he engaged with and the works he composed as a result. Of particular interest to me are Chopin’s Fantasies (i.e. op. 44, 49 and 61). As Fantasy is a common genre title in the history of Western music, few scholars consider the possibility that Chopin’s “fantasy” had a special intention, but what I find curious is that the solo piano works that Chopin himself regarded as “Fantasies” were all written in the 1840s, the last decade of his life. I have therefore been based at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris since 2022 (transitioning to the status of Associate Fellow there upon becoming an Assistant Professor at WIAS in 2024) and continue to pursue this theme. During the course of this research, I became aware of the fact that the French novelist George Sand (1804-76), Chopin’s famous lover, wrote the Essay on Fantastic Drama in 1839, which Chopin praised as “the most wonderful article” in a letter to his friend.

Mickiewicz’s Dziady Part Ⅲ as seen in Sand’s evaluation

In Sand’s Essay, the dramas of three writers (Goethe’s Faust, Byron’s Manfred and Mickiewicz’s Dziady Part Ⅲ) are evaluated side by side, but it was Mickiewicz’s drama which was praised as the best “fantastic world”. Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855) is one of the most famous 19th century poets in Poland and one of the so-called “Grande Émigration / Wielka Emigracja”, who exiled themselves to France at about the same time as Chopin. However, both the poet’s name and this work are lesser known than the other two, and some previous studies have questioned Sand’s review. Nevertheless, it is my opinion that her evaluation is fair, because the ideas and the world described in her novel Spiridion (1839) have much in common with the ideas and the world described in Dziady Part Ⅲ. In other words, it can be assumed that she had a strong sympathy for this drama and that it had some influence on the writing of her Spiridion.

The general theme of Dziady is the traditional festival of ancestral spirits in the Polish-Lithuanian region, and in Part Ⅲ the main theme is the rule of the Russian Empire over Poland in the 19th century. In the first scene of Part Ⅲ, the protagonist, Konrad, whose experiences are projected onto Mickiewicz’s own, is arrested and imprisoned by the Russian authorities. The other prisoners are mostly real friends of Mickiewicz’s, and they talk about their arrests, the fate of their relatives and other prisoners, and the deportation of a group of students to Siberia. This scene gives a realistic description of the hardships they faced. The second scene, entitled “The Great Improvisation”, features a monologue by Konrad, who, possessed by the devil, demands divine power to increase the greatness of his nation. This part is notable in that the protagonist is heading towards a crisis of blasphemy against God.

By this time, France had gone through several revolutions and was beginning to free itself from the confines of Christianity and embrace a higher philosophy. Meanwhile, in the 1830s, Poland was still suffering from its resistance to the Russian Empire. Sand noted that it was during this period of great pain that Mickiewicz’s ideas attempted to transcend pious Polish Christian thought, which she praised most highly: “Oh, great poet! Philosopher in spite of you!”

Impact on Sand’s novel Spiridion

Sand herself was raised in a strict Catholic family in France, and she felt great empathy for the position of women in a male-dominated society and for vulnerable groups such as immigrants. Her novel Spiridion was written in a monastery cell in Mallorca, where she spent the winter of 1838-39 with Chopin. The main theme is that the protagonists, who are monks in a Catholic monastery, are searching for what to believe in the face of the corruption of Catholicism. It is clear, therefore, that the words of the protagonist, Alexis, often contain a questioning of the Christian God and an examination of alternative ideologies, such as Judaism, ancient philosophy and heretical thought by Pierre Abélard (1079-1142, French theologian, philosopher and father of Scholasticism).

Interestingly, a similar ideological chaos and crisis of blasphemy is evident in Dziady Part Ⅲ. In a prison cell converted from a monastery cell, the protagonist Konrad looks down on the peoples like Moses on Mount Sinai, where he finds an ancient Roman oracle. Konrad calls himself Zeus (the supreme god of ancient Greece) and begins to demand the power of the Christian God. I argue that Sand has captured in these monologues of Konrad the exploration of ideologies in different directions beyond Christianity, and that this exploration is reflected in her novel.

Possibility of the influence on Chopin’s “fantasy”

Let us now return to the first question. Impressed by Sand’s manuscript praising Mickiewicz’s Dziady Part Ⅲ, could Chopin’s “fantastic” works have been influenced by the “fantasy” of these two artists? My research is currently in the process of proving this hypothesis, but I believe that this “fantasy” can at least be related to the features and commonalities of op.44, 49 and 61.

In particular, op. 49 begins with a funeral march. Meanwhile, the common theme of all parts of Dziady is the commemoration of the souls of the dead. Furthermore, in the prologue to Dziady Part Ⅲ, Gustaw, who was the main character of the previous parts, has died and is reborn here as Konrad. It can therefore be stated that this drama itself begins with “death.”

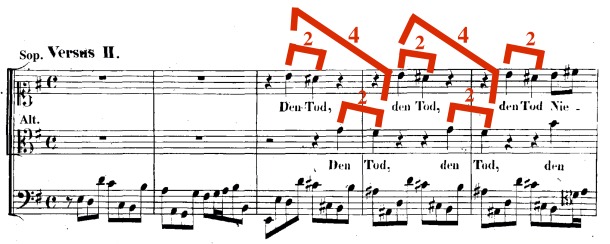

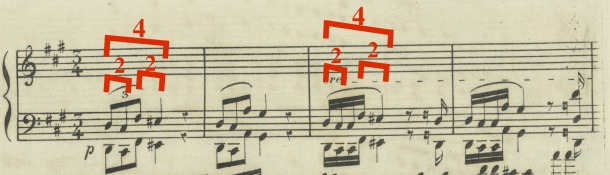

Further, op. 44, 49 and 61 have in common the descending 4th motif, which contains or is linked to the descending 2nd motif. It is well known that the descending 2nd was often used by J. S. Bach (1685-1750) as a motif to express emotions such as “distress,” “melancholy,” “sorrow,” and “death.” However, in the context of Chopin’s “fantastic” works, it is important to note that the descending 4th, which includes the descending 2nd, is commonly used. An analysis of Bach’s compositions reveals an example of the use of the descending 4th in the second variation of the chorale Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt (Nobody could restrain death) in the Easter cantata Christ lag in Todesbanden (Christ lay in death’s bonds) BWV 4.

J. S. Bach, Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt, mm. 1-5. (Breitkopf und Härtel, 1851)

F. Chopin, Polonaise op. 44, mm. 1-4. (Maurice Schlesinger, 1841)

F. Chopin, Fantaisie op. 49, mm. 1-2. (Maurice Schlesinger, 1841)

F. Chopin, Polonaise-Fantaisie op. 61, mm. 1-2. (Brandus, 1846)

This cantata has a total of eight pieces (theme and seven variations) and, with the exception of the second variation, the text praises the resurrected Christ and sings the joy of life. In contrast, the second variation is a text that deals entirely with death as a human sin. In my opinion this is relevant because it is a text that overlaps with Dziady and the ideas of the Polish Christians of the time. Chopin especially held Bach in high respect, and during his stay in Mallorca with Sand he brought Bach’s scores with him and composed his Préludes op. 28 as a homage to Bach. While other relevant examples should be identified to further refine this analysis, I believe at this stage the above work provides a compelling example.

Prospects for this project

Thus, this research project is ongoing, and I am now pursuing the “fantasy” for these three artists from the 1840s onwards. The most significant aspect for me is that the metaphysical inquiries concerning the nature of reality or unreality for human beings in extreme circumstances, and the concept of God, are indeed “fantasies” shared by these artists. The spirituality explored by the Poles of the time, who were forced to choose between exile or combat, can overlap with the spirituality of people in regions such as Ukraine today, who are fighting for their lives in despair at the possibility to retake their territory. By examining such struggles some 200 years ago, it may be possible to shed light on contemporary issues such as the nature of spiritual salvation and the meaning of religion for them. I continue to hope that this is the role of the humanities and that this is part of what I can contribute in some small way through my research.

Reference: Trois Fantaisies de Frédéric Chopin : une inspiration des œuvres de George Sand et d’Adam Mickiewicz