SATO Yuko, Assistant Professor

The rise of autocratic regime ― Mechanisms of autocratization

My specialty is in comparative politics and the study of political regimes worldwide. My study identifies the processes by which political regimes change and the factors contributing to such regime transformations.

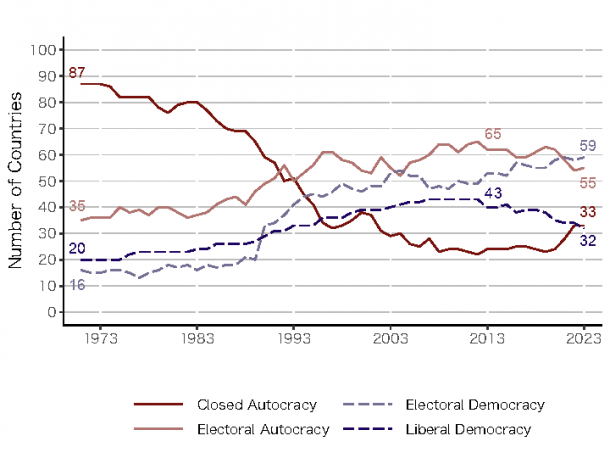

Political regimes can be categorized into two main types: democracy, such as the one in Japan or the US, and autocracy, such as the one in China or Russia. Democracy is a political regime in which national representatives are elected through free, fair, and competitive elections. On the other hand, autocracy refers to a political regime in which free, fair, and competitive elections are not guaranteed, or the country’s representatives are not directly elected by its citizens, such as a military dictatorship or a monarchy. Regime changes can occur due to various factors, including international situations or economic conditions. In recent years, a growing number of countries have become autocratic regimes (Figure below).

Figure: Countries’ political regimes are categorized into democratic (blue) and autocratic (red) groups, with darker colors indicating countries with stronger democratic or autocratic characteristics. The figure encompasses 179 countries in total.

Source:Nord, Marina, Martin Lundstedt, David Altman, Fabio Angiolillo, Cecilia Borella, Tiago Fernandes, Lisa Gastaldi, Ana Good God, Natalia Natsika, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2024. Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot. University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute. (Replicated by Sato using the V-Dem Data Version 14)

The figure above shows that most countries were classified as closed autocracies (dark red) during the Cold War. Since the end of the Cold War, the influence of the US and Western Europe has grown, leading to an increase in the number of democratic regimes (blue group) throughout the 1990s and 2000s. However, since around 2020, there has been a rapid rise in closed autocracies (dark red), surpassing the total number of liberal democracies (dark blue) by 2023. This worldwide trend of declining in the quality of democracy is known as autocratization. Recent studies suggest that rising affective polarization, where public opinions are divided into two opposing groups, significantly contributes to this trend.

Targeted protests and rising affective polarization in Brazil

While conducting field research in 2013-2014, I encountered nationwide anti-governmental protests in Brazil. Since its democratization in 1985, the quality of democracy in Brazil has improved significantly over time. However, the country has recently experienced a reversal trend, autocratization (observed from 2015-2022), following the series of protest events preceding this period. I thus hypothesized that these protest events may have contributed to the autocratization process in Brazil. Particularly, I estimated that protests have impacted the rising anti-democratic values among citizens by promoting affective polarization. This is the topic of my book project, which I am currently working on.

Brazil’s Workers’ Party (a left-wing party) has been the ruling party for over a decade (2003-2016). While the government initially received high popularity among the citizens, such popularity declined due to economic stagnation and increased public spending on hosting the 2014 Football World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. As citizens’ dissatisfaction accumulated over time, nationwide protests against the government spread in 2013. Additionally, Brazilian society became further fragmented due to the corruption scandal (known as Lava Jato or Operation Car Wash) involving members of the Workers’ Party, including current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (President of Brazil in 2003-2010 and 2024-).

With such a political crisis, a far-right group seized the opportunity to gain political support. Jair Bolsonaro, a former military officer and President of Brazil from 2019-2022, also gained prominence during this period by employing social media campaigns to confront political establishments, particularly the Workers’ Party. Bolsonaro, often compared to Donald Trump in the US, is also well-known for his radical-right ideology, including his disrespectful stance on women’s rights in his defense of “traditional family values” and his advocacy for military intervention to improve security. His extreme political stance led to protests against him, particularly mobilizing women’s groups (Photo below).

Photo: Anti-Bolsonaro protest on Paulista Avenue, São Paulo’s main avenue, on March 8, 2020, World Women’s Day. Red is the symbolic color of the Workers’ Party. “CONTRA BOLSONARO” at the bottom of the photo means “anti-Bolsonaro,” and “MULHERES PELA DEMOCRACIA” in the center means “women for democracy.” (Photo credit: Sato)

To reveal the impact of protest events on public opinion, I conducted an empirical study focusing on the widespread protest against Bolsonaro during the 2018 presidential election campaign. The movement initially started as a social media campaign called #Ele Não (meaning “Not him”) and later developed into a physical protest event that occurred in 114 cities on September 29, 2018, with support from the Workers’ Party and other left-wing parties.

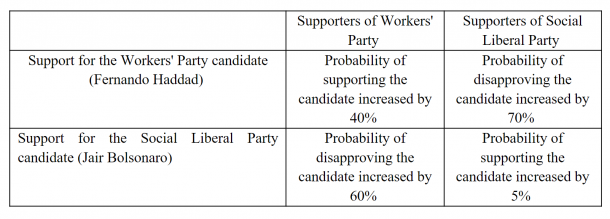

The table below shows the results of a statistical analysis on changes in the probabilities of supporting each candidate before and after the Ele Não protest. The analysis utilized survey data from approximately 5,000 voters at eight different times. Two questions asking citizens’ voting intention were used: “Who will you vote for in the next presidential election?” (supporting the candidate) and “Who you would never vote for as a presidential candidate in the next election?” (disapproving the candidate).

Table: Changes in voters’ support for candidates before and after the protest against Jair Bolsonaro (a candidate of the Social Liberal Party). The protest was mainly organized by Workers’ Party supporters. The table demonstrates that the affective polarization increased after the protest event. (The table was prepared by Sato based on the data from Datafolha, a Brazilian survey company)

The result indicates that protests raised the probability of people voting for the candidate of their supporting party and increased the probability of disapproving of the candidate from the opposite party. This division in support of the candidates suggests that the protests may heighten mass affective polarization.

From Polarization to Integration

While I have been mainly studying the mechanism of rising affective polarization, I plan to extend my study to find ways to reduce polarization for future studies.

To achieve this, I plan to continue studying Brazil, which is currently seen as a successful case of restoring democracy by reducing affective polarization. At the same time, I plan to systematically analyze the impact of major political events on affective polarization in autocratizing countries, such as military coups or presidential impeachment, and make international comparisons.

Coverage/Constitution: Keiko AIMONO

Cooperation: Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University, J-School