ANDASSOVA, Maral, Assistant Professor

The Appeal of Ancient Japanese Literature

I am researching Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki (Cultural and Geographical Record of Izumo Province), which was compiled in the early 8th century.

There are an abundance of highly interesting myths set in Izumo that appear in the Kojiki, which is the primary theme of my research. The myth about creating and transferring the land in which the central deity of Izumo Grand Shrine, Ohonamuchi plays a part, is a particularly important motif common to the Kojiki (An Account of Ancient Matters), Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan) which I am also researching, and Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki. However, the depictions of the deities in these three works of literature that were written at nearly the same period are subtly different. I began studying Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki after researching the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki out of a desire to research their similarities and differences to contemplate what message is being conveyed from Izumo.

Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki was long understood to be a geographical account and considered a secondary resource for understanding the myths in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, but recently research has been carried out uncovering the value of Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki in and of itself. For instance, there is the view in literary studies that, while it is influenced by the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, it was written based on the understanding and assertions of the person ultimately responsible for its compilation, Hiroshima who was the Izumo high priest (provincial governor with ritual responsibilities). Given this, I am focusing on the article on the community Ihinashi, section of Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki that is thought to reflect the ideas of Hiroshima as the person presiding over religious rituals in Izumo.

I was born and raised in Kazakhstan, and became interested in ancient Japanese literature in high school after reading The Pillow Book in Russian. I was surprised to find that the emotions I was experiencing at the time were also expressed in the text, though separated by geography and a thousand years. Later, I came to Japan as an exchange student, discovered there are even older books, and began studying the Kojiki.

The compilation of the Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, and Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki

The Yamato court formed a centralized state under the ritsuryo system that was developed around the emperor through the Taika Reform and enactment of the Taiho Ritsuryo Code from the 7th to early 8th centuries. At the start of the 8th century, a directive was given to compile the historical records of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, which includes myths, to establish the foundation of the nation.

Meanwhile, orders were given to create and submit regional cultural and geographical records in each province. These written reports were later regarded as “fudoki” (cultural and geographical records). Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki is the only one that remains today in a nearly complete state. Information written at the end of the text states that Hiroshima of Izumo (Senior Sixth Rank, Upper Grade, Twelfth Order of Merit) who rules over the district of Ou as governor was involved in its compilation. Hiroshima participated in government as the district governor of Ou appointed by the central government, and also appears to have held authority over rites for the deities throughout Izumo as the Izumo high priest.

The myth about creating and transferring the land is the story of Ohonamuchi, the deity of Izumo (in the Kojiki, he appears under the name Ohokuninushi), creating the earthly world and transferring the right to rule to the ancestral deity of the Imperial Family, Amaterasu. When Ohonamuchi created Ashihara no Nakatsukuni (the earthy world), Amaterasu said, “My offspring should rule over it,” and sent envoys to Ohonamuchi one after another. In the end, Takemikazuchi succeeded in negotiating for the right to rule, and Ohonamuchi built a splendid palace (Izumo Grand Shrine in Photo 1) and agreed to transfer control of the land in exchange for being enshrined there.

Photo 1. A model of the ancient Izumo Grand Shrine

Izumo Grand Shrine is thought to have been 129 m in height. Photographed at the Shimane Museum of Ancient Izumo

Sharing a meal with deities

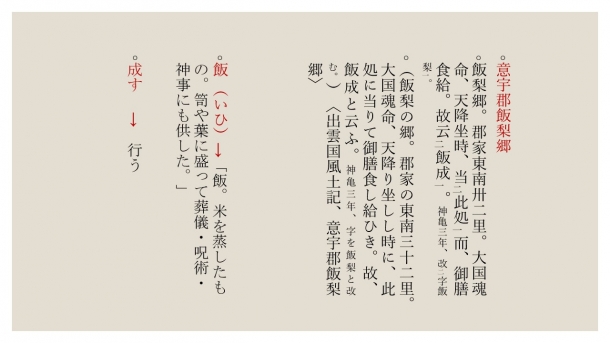

In addition, in the “District of Ou, Community of Ihinashi” narrative (Photo 2) of Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki, the deity called Ohokunitama no kami who is seen as a godhead unique to that text appears. This deity is evidently a deified name for the spirit of the great land.

Photo 2. “District of Ou, Community of Ihinashi”

In modern-day language it says, “Community of Ihinashi. 32 ri (1 ri equals approx. 3.927 km) from the district governor’s office. When Ohokunitama no kami came down from the heavens, he ate (“nashita”) a meal (“ihi”) exactly in this spot, so it is called Ihinashi (726).” As eating a meal is a part of ritual ceremonies, the place name indicates a divine meaning.

In the Kojiki, the words “ohomike” and “mike” refer to offerings given to the deities, and the word “miihi” is also understood to mean other meals dedicated to deities. Therefore, that same narrative is interpreted as Ohokunitama going down to Community of Ihinashi in the district of Ou, presenting sacred offerings to the deities of the land and also partaking of them.

Why does Ohokunitama also eat the offerings? A hint can be seen in the “hitsugi” ritual and “shinjyoe” ceremony that were handed down through generations of the Izumo high priest family. In the “hitsugi” ritual conducted when there was a change in provincial governor, he presents rice that has been cooked by a sacred fire to the deities and consumes it before them. The same ritual was also carried out in the “shinjyoe” held every year. It is thought that by sharing a meal with the deities, the provincial governor takes on the spirit of the deities and becomes one with them. The “hikiriusu” (flint mortar) and “hikirigine” (flint pestle) used to start the fire that cooks the food offering are regarded as sacred implements of the Izumo high priest family and enshrined in the Sankaden Hall of Kumano Grand Shrine.

Photo 3. Sankaden Hall at Kumano Grand Shrine

In other words, Ohokunitama eating the offerings at Ihinashi can be interpreted as becoming united with the deities of Izumo. It may be that because Hiroshima, who was stationed in Ou district, projected himself as Ohokunitama and took on the spiritual power of the Izumo deities by compiling the article of community of Ihinashi.

In the early 8th century, the Izumo high priest proceeded to Yamato in a period when the emperor’s enthronement was at hand, and carried out “kamuyogoto,” the ritual greetings to the emperor by the highest priest of Izumo Grand Shrine. There, the provincial governor stated that he embodies the deities of Izumo and communicated good wishes as the representative of the deities residing in the 186 shrines throughout Izumo.

Izumo and Yamato shared religious and ritual circumstances centering on “kamuyogoto.” Conceivably, Hiroshima was cognizant of his relationship with the Yamato court and thus composed the “Community of Ihinashi” section to elevate his own charisma as the conductor of rituals worshiping the deities of Izumo. It can be said that Izumo no Kuni no Fudoki was created to reflect the unique viewpoint of the Izumo high priest rather than unilaterally accept the myths compiled by the central government.

Coverage/Constitution: INOUE Yuko

Cooperation: Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University, J-School