FAHEY Robert Andrew, Assistant Professor

With the growth in popularity of social media in recent years, we have also seen an increase in the effects of conspiracy theories on society

My current research theme asks what sort of effects conspiracy theories are having on people’s political activities, such as voting in elections. A conspiracy theory is a belief that important incidents and events are the result of conspiracies and stratagems by powerful individuals and groups – that the truth of the world is not what most people think it is. Similar words such as dema (a Japanese word for false rumors or propaganda, from the German demagogie) or “fake news” exist, but conspiracy theories are specifically defined by a belief in machinations and stratagems executed for nefarious and selfish purposes by groups acting behind the scenes.

With the rapid growth of social media in recent years, the speed with which all forms of information – including conspiracy theories – can spread has increased dramatically. Moreover, unstable social conditions created by events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have caused a constant flow of new conspiracy theories which appear and then spread worldwide in a flash. Aside from basic concerns about these theories’ veracity, we have also seen that conspiracy theorists can cause very serious incidents. One famous example is the Capitol Riot in the US in January 2021, wherein supporters of ex-President Trump, believing the conspiracy theory that “the election was stolen”, forced their way into the Capitol Building to stop the election result from being approved. I believe that politically motivated riots like these demonstrate the growing effects that belief in conspiracy theories have on society and politics.

As to my own background, I was born in Ireland and lived there until I finished secondary school, later becoming a journalist in the UK. I had a lot of opportunities to write about Japanese companies and became interested in the Japanese language, entering a university where I could learn Japanese as well as political science. I subsequently had the good fortune to study political science at Waseda University, where I’m now a researcher. When I was a journalist, I personally witnessed social media’s growing effects on companies and individuals. As the popularity and power of social media grew, I felt that conspiracy theories’ effects on society have also increased, and decided to focus my research on this theme.

GCBS, a tool for measuring conspiracy theory belief metrics

Research on conspiracy theories in the political science field began as long as 70 years ago, in 1950s America. At that time, belief in conspiracy theories was thought to be a kind of mental illness or disorder. However, research within just the last 20 years has revealed that belief in conspiracy theories is far too common to be considered a disorder; rather, surveys have shown that most people around the world believe in at least one conspiracy theory.

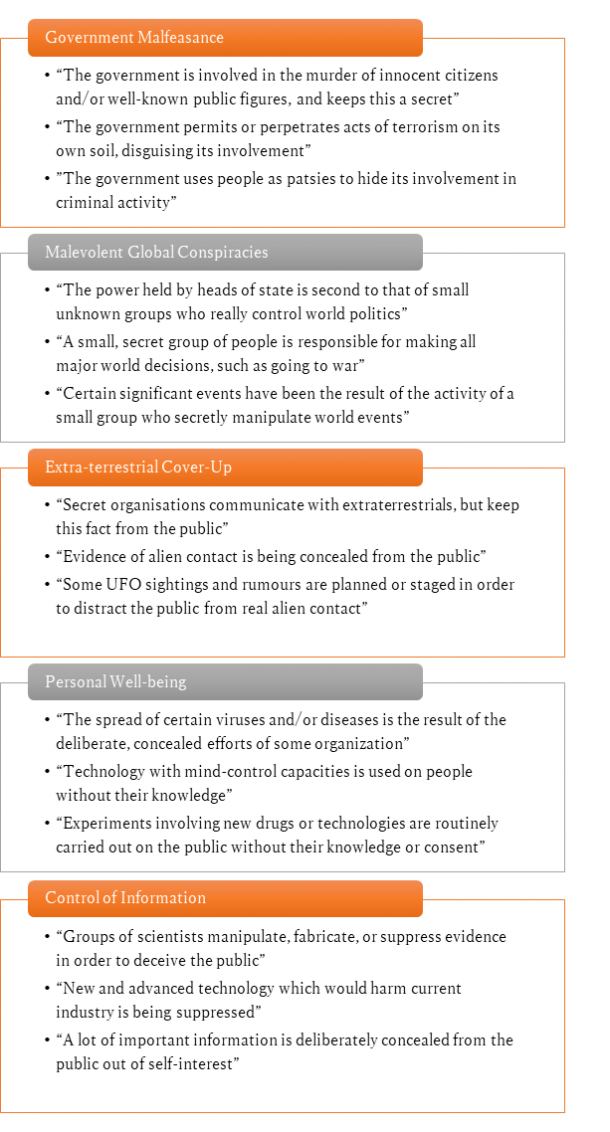

The Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale (GCBS) (Diagram 1) was developed by Brotherton et al in 2013 as a tool for measuring conspiracy theory belief metrics in surveys. It’s utilized by researchers as a yardstick to assess the extent of an individual’s conspiracy beliefs, and their effects on society and politics.

Diagram 1: The Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale (GCBS). Conspiracy theories are broadly divided into 5 factors with 3 items each, for a total of 15 conspiracy theories.

In the GCBS, conspiracy theories are broadly divided into five factors with three items each, for a total of 15 conspiracy theory examples. The five factors are 1) government malfeasance, 2) malevolent global conspiracies, 3) extraterrestrial cover-up, 4) personal well-being, and 5) control of information. Factor 1 (government malfeasance) includes examples such as: “the government allows terrorism against its own nation, or even participates in it and falsifies its participation”. Factor 2 (malevolent global conspiracies) includes items like: “small, secret groups are responsible for critical decisions in the world, such as starting wars”. The conspiracy theories in Factor 3 (extraterrestrial cover-up) include “secret organizations are contacting extraterrestrial beings, but hiding the truth from the masses”, Factor 4 (personal well-being) includes “a certain pathogen or disease’s spread is a result of careful, concealed activities by a certain organization”, and Factor 5 (control of information) includes “groups of scientists are manipulating, forging, or hiding evidence in order to deceive the masses”.

A GCBS table with these 15 conspiracy theories on it is distributed as part of many public opinion polls; survey-takers are asked to respond indicating whether they believe the theories or not. When examining the results, the more a person responds saying they believe various items, the greater the overall belief in conspiracy theories is said to be for that subject of the poll.

This measurement method using GCBS is very useful and is now widely utilized, but I believe there are flaws with this method. The conspiracy theories in GCBS were generated by scholars in the US and Europe – where there has been extensive research on conspiracy theories are rampant – and as a result, the content is arguably biased toward US and European thought and actions. For instance, we might expect responses to Factor 3 (extraterrestrial cover-up) to naturally differ greatly between Americans and Japanese, since their cultures and lifestyles are very different, and they may not be exposed to the same narratives about extra-terrestrial conspiracies.

Developing a new measurement tool to replace GCBS

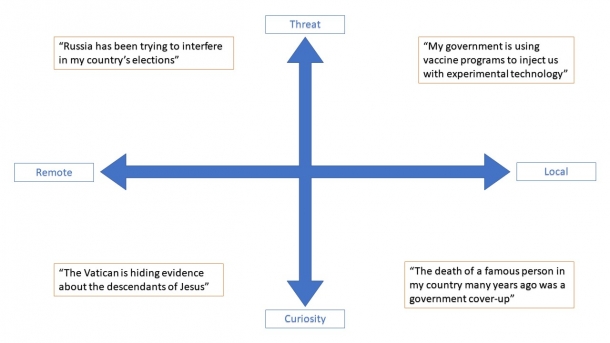

Consequently, I am working on devising a new measurement tool based on the theory illustrated in Diagram 2. The X axis of the diagram plots one’s perceived distance from the people responsible for each conspiracy theory, leftward being “further from me” and rightward being “closer to me”. The Y axis plots whether one feels like each conspiracy theory is actually a threat to yourself and your community, upward being “threatening” and downward being merely “curious”. Rather than 15 predetermined items as in the GCBS, conspiracy theories used in survey questions are selected to match the survey’s content, and questions are asked to allow us to see where respondents place the conspiracy theories. For example, let’s consider the famous conspiracy theory that “Princess Diana’s accidental death was a cover-up by the British government”. As an Irish person who worked in the UK, I might find it rather “close to me” (since I lived in the country ruled by that government), but it’s not directly relevant to my life, so I would say that it is “curious” (rather than threatening), and would place it in the lower-right. However, most Japanese people would find the theory “far from me” (since the British government has no relevance to their daily lives), and would probably also find it “curious rather than threatening”, so they would place the conspiracy in the lower-left.

Diagram 2: The X axis plots one’s perceived distance from conspiracy actors while the Y axis plots how one feels about conspiracy theories, upward being “threatening” and downward being “curious”. Rightward indicates “closer to me” and upward indicates “threatening”. Appropriate placement will depend on the respondent; the above is an example.

Using this method, appropriate placement will vary based on the respondent even if the questions are the same, delivering results that are more complex, but also more accurate and useful. I believe this will also enable the selection of optimal conspiracy theories to include in surveys for a given country or region. However, the question of how to create survey measurements that accurately locate each conspiracy theory’s position on this diagram is the next challenge for my research. Going forward, I wish first to perfect this measurement method, then to delve more deeply into my research theme: the cause-and-effect relationship between belief in conspiracy theories and political activities such as voting or violence.

References

- Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring Belief in Conspiracy Theories: The Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279

- Majima, Y., & Nakamura, H. (2020). Development of the Japanese Version of the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale (GCBS-J). Japanese Psychological Research, 62(4), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12267

Coverage/Constitution: AIMONO Keiko

Cooperation: Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University, J-School