KONDO Aki, Associate Professor

Judgment of facial attractiveness is swayed by the immediately preceding judgment

I specialize in experimental study. I am particularly interested in and research the mechanism of people’s perception and judgment.

It is known that the impression (perception) of what a person views is impacted by what was previously viewed. Similarly, the judgment of what is viewed is also influenced by the previous judgment. To explore the mechanism that gives rise to this kind of history effect, I have designed experiments on perception and judgment that focus on facial attractiveness and closely analyzed the results.

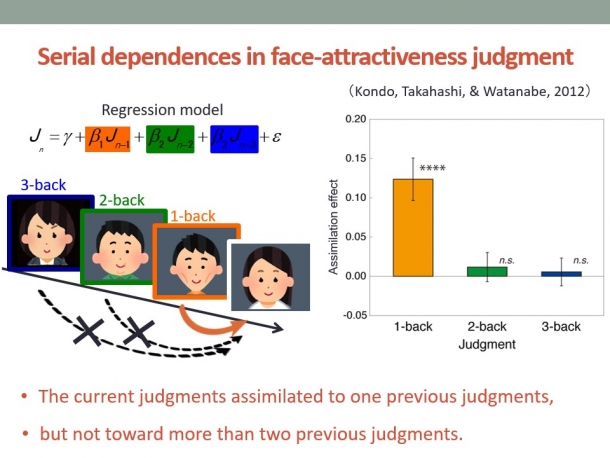

First, I conducted an experiment to examine history effect in judgment (Figure 1). Experiment participants were shown successive photos of people’s faces and asked to judge the attractiveness of each on a scale of 1 to 7, ranging from “not at all attractive” to “very attractive.” The results of this experiment showed that, even when shown a photo of the same face, when participants judged the face in the immediately preceding photo as attractive, there was a tendency to judge the next photo as more attractive; and when they judged the immediately preceding photo as unattractive, there was a tendency to judge the next photo as more unattractive. Judgments on the photo viewed before the immediately preceding image, as well as the photo before that, had no impact. This experiment found that judgment of facial attractiveness is swayed by the judgment made in the immediately preceding assessment.

Figure 1.Experiment to examine the impact the most recent judgment has on judging facial attractiveness

In this experiment, the participants were shown a mix of men’s and women’s faces. When I analyzed the results focusing on whether the immediately preceding photo was the same sex or different sex, I found that when the photo was of the same sex there was a strong tendency to be swayed by the immediately preceding judgment, but that influence was weak when the photo was of a different sex. On the other hand, this outcome distinguished by sex did not occur when judging the same photo for “roundness of face” or “intelligence.” This is surmised to be because the participants unconsciously switched the judgment criteria according to sex when judging facial attractiveness.

When viewing an attractive face, the face seen immediately after is also viewed as attractive

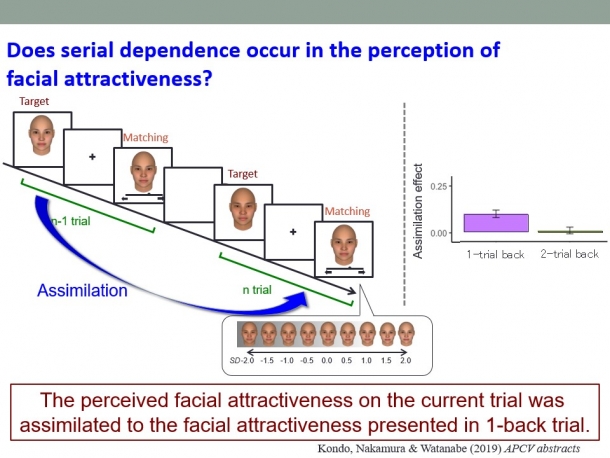

Next, I conducted an experiment that examined history effect in perception (Figure 2). In this experiment, images of faces created by a computer were used rather than photos of faces. First, based on a computational model of facial attractiveness, 9 faces were created from a single face that quantitatively changed the degree of attractiveness by incrementally altering features such as eye size and skin shade. Then, participants were shown one face (target image) out of 7 faces, excluding the 2 images of the most extreme degrees of attractiveness. They were asked to press keys to morph the on-screen image into the 9 alterations of the face and choose the one they thought was identical to (matched) the target image. This was to study how attractive the participants viewed the target image.

This experiment found that when a highly attractive target image is viewed in the immediately preceding image, there is a tendency for the next target image to be viewed as more attractive than it actually is. Swayed by the immediately preceding assessment, the subsequent image is also viewed as highly attractive. The face viewed before the immediately preceding image had almost no impact.

Figure 2.Experiment to examine the impact of the facial attractiveness of the immediately preceding image on the impression of facial attractiveness

Furthermore, I created 9 other images from a different face and conducted the same experiment so that target images of the 2 source images would randomly appear. In this experiment, when the immediately preceding image was a face from a different source image, there was no tendency for the participants to be swayed by their impression. This showed that the fewer differences from the face seen in the immediately preceding image, the easier it is to be swayed by the immediately preceding assessment.

The desire to help eliminate bias in perception and judgment

I have assisted in a senior researcher’s experiment that studied brain activity when judging luminance. In that experiment, we randomly showed participants various degrees of luminance, but realized that at times both judgment and brain activity changed even when shown the same luminance. Wondering why, we compared instances when the previous luminance was bright and when it was dark, and found that participants were swayed by the immediately preceding luminance.

It is believed that the phenomenon called anchoring is associated with this outcome. Anchoring refers to, when information content is limited, the tendency for a subsequent judgment to be similar to the immediately preceding judgment because that preceding judgment is used as a criterion. This phenomenon is likened to an anchor that is lowered to secure a boat so that it does not move. It likely serves as the mechanism that leads to a subsequent judgment that luminance is bright if the previous luminance was assessed to be bright.

However, wouldn’t the outcome be different if, instead of a target with a physical assessment scale for something like luminance, the target being assessed, such as facial attractiveness, was judged based on the participants’ subjective criteria? Believing this to be true, I designed this study. I presumed judgments would not be swayed by the preceding assessment if the target were judged by subjective criteria, but the results were identical to the experiment on luminance. Moreover, quite interestingly, the experiment on perception conducted afterward showed that not only judgment, but also the impression of facial attractiveness is swayed by the immediately preceding assessment.

Going forward, I plan to carry out experiments to analyze history effect in greater detail. In this study, the experiments on judgment and perception were conducted with different groups, but I intend to explore the mechanism that gives rise to history effect by conducting experiments on perception and judgment with the same participants and examining the relationship of susceptibility to influence.

In real life there are various instances in society when people can be biased by prior perceptions and judgments, such as in interviews and scoring competitions. I hope to contribute to achieving impartial judgments in such situations through scientifical analysis in the laboratory to clarify the mechanism that leads to bias and suggest ways to eliminate bias that anyone can implement.

Coverage/Constitution: Seiko Aoyama

Cooperation: Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University, J-School