FITTLER Áron, Assistant Professor

The difficulty of translating waka

I study methods of translating waka, the earliest form of Japanese poetry, into foreign languages. The physical properties of nature (natural features) such as flowers, rain, and guideposts are expressed while human emotions (human affairs) are simultaneously denoted within a poem’s 31 syllables by sprinkling the prose with kakekotoba, words that possess two or more meanings depending on the homophonous expression, and engo, words that are strongly related due to theme or pronunciation.

Translating waka characterized by these homophonous expressions and two contexts is an extremely difficult task given that there are cultural differences and the sound of the original text is lost. Here, I explore the problems in translations to date, and together with my own translations, introduce a new translation method that attempts to more accurately communicate content while retaining the expressions particular to waka.

I studied Japanese and classical Japanese literature in Hungary. I feel a close relationship exists between humans and nature in Japanese literature, and that spirit is deftly expressed in waka. The timbre of waka is beautiful, so I have also read the original texts.

Frequently used similes

In the Heian period, feelings were conveyed to one another through waka. The poems were a means of communication for the nobility. At the time, there were conventional patterns of expressions in kago (words used in waka). For example, there was the practice of using the phrase, ‘(ame ga) furu (rain will fall)’ to mean ‘grow old’ or ‘time will pass.’ As a result, the sound of the word, furu would be associated by the people in that time with the two contexts of human affairs and natural features, such as ‘rain will fall,’ ‘become old,’ ‘grow old,’ and ‘time will pass.’

The distinguishing feature of waka is the close connection between nature and humans, and their parity, within a single poem. However, there are many examples in foreign-language translations of nature simply serving as a backdrop or tool for explaining human emotions. Often, the relationship between human affairs and natural features is translated with similes using ‘as’ and ‘like’ (no you ni). In addition, this method requires supplementing with content not in the original text to explain the association between human affairs and natural features. When similes are frequently used, the expressions become monotonous and explanatory, and there is a tendency to lose the diversity of rhetoric in waka.

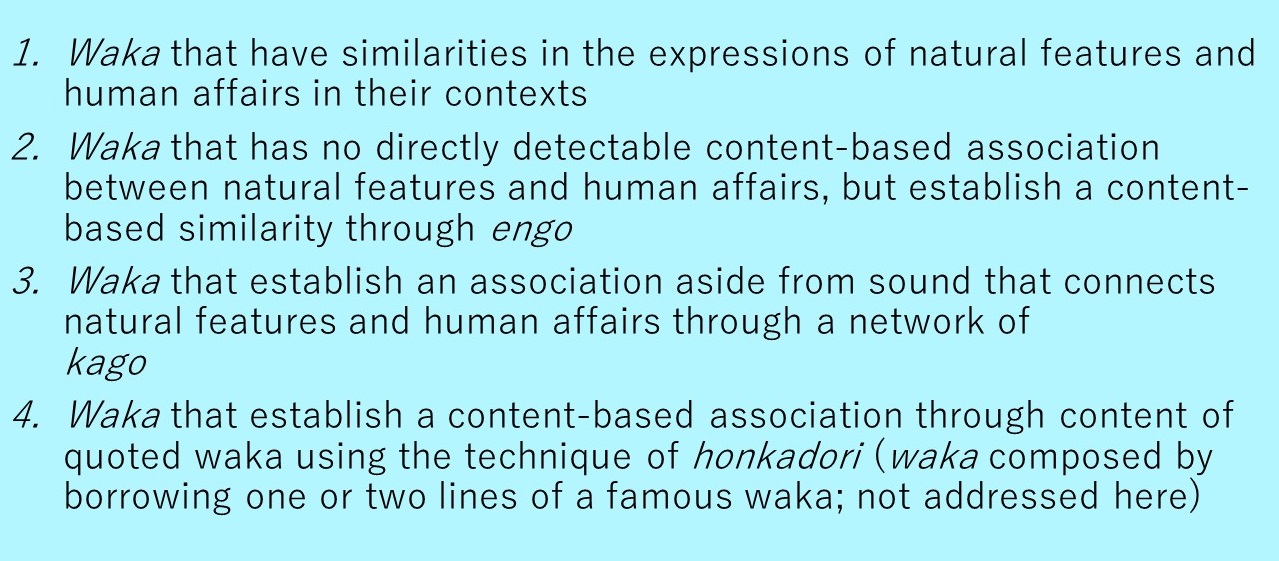

I have divided waka that include homophonous expressions into 4 groups according to the content association between natural features and human affairs, and created a suitable translation method for each (Fig.1).

Fig. 1: Classification of waka that include homophonous expressions according to content association between natural features and human affairs

In the case of 1 and 2, an allegorical translation that also implies a context of human affairs while centering on the context of natural features enables expression that brings parity to natural features and human affairs. Homophonous expressions used in 3 can be considered conventional phrases often used in waka. In this instance, I analyze what kinds of words these conventional phrases are paired with in other waka and, if necessary, use kago with an associative relation to the conventional phrases to supplement the content.

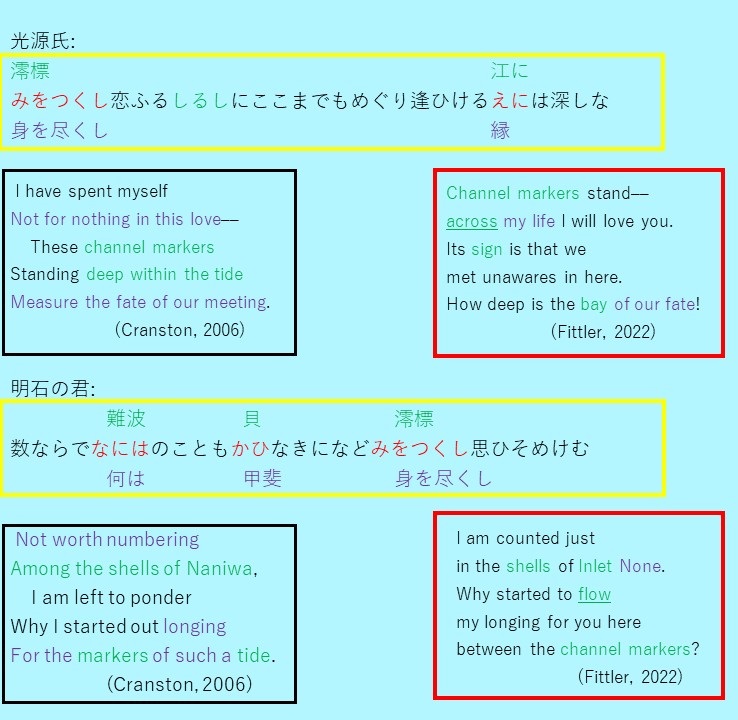

Here, I illustrate 3 using the poetic exchange between Hikaru Genji and Akashi-no-Kimi in Miotsukushi (Channel Markers) from “The Tale of Genji.” The following is a comparative review of a previous translation and my own translation (Fig. 2).

When Genji visits Sumiyoshi Taisha Shrine near Naniwa Inlet, Akashi-no-Kimi who coincidentally happened to be there sees his splendid appearance. Akashi-no-Kimi is again made aware of their difference in social standing. She stays silent and leaves, but later Genji finds out about it and sends her a waka.

Fig. 2: Poems exchanged between Hikaru Genji and Akashi-no-Kimi; translations by Cranston and Fittler

“Miotsukushi” is kakekotoba that is a play on the word, miotsukushi, referring to channel markers often seen in Naniwa Inlet (guideposts placed in shallow inlet waters), and mi wo tsukushi, meaning to offer up oneself. Since there is no association between these two words aside from sound, in many translations only the human affairs context of offering up oneself is translated.

Cranston’s translation (bordered in black) is one of the few examples that express both the human side and natural features. However, in the translation the inherent meaning of miotsukushi (channel markers that serve as guides) is rendered as “These channel markers, Standing deep within the tide, Measure the fate of our meeting.” The content differs from the original text.

The first 2 lines of Akashi-no-Kimi’s poetic reply are wonderfully translated by Cranston who uses a metaphor to link human affairs and natural features by expressing her low social standing as “Not worth numbering, Among the shells of Naniwa.” Nevertheless, it seems that “tide” is used with the intention of expressing her longing for Genji and miotsukushi (channel markers) that measure the depth of the tide, so again the meaning differs from the original text.

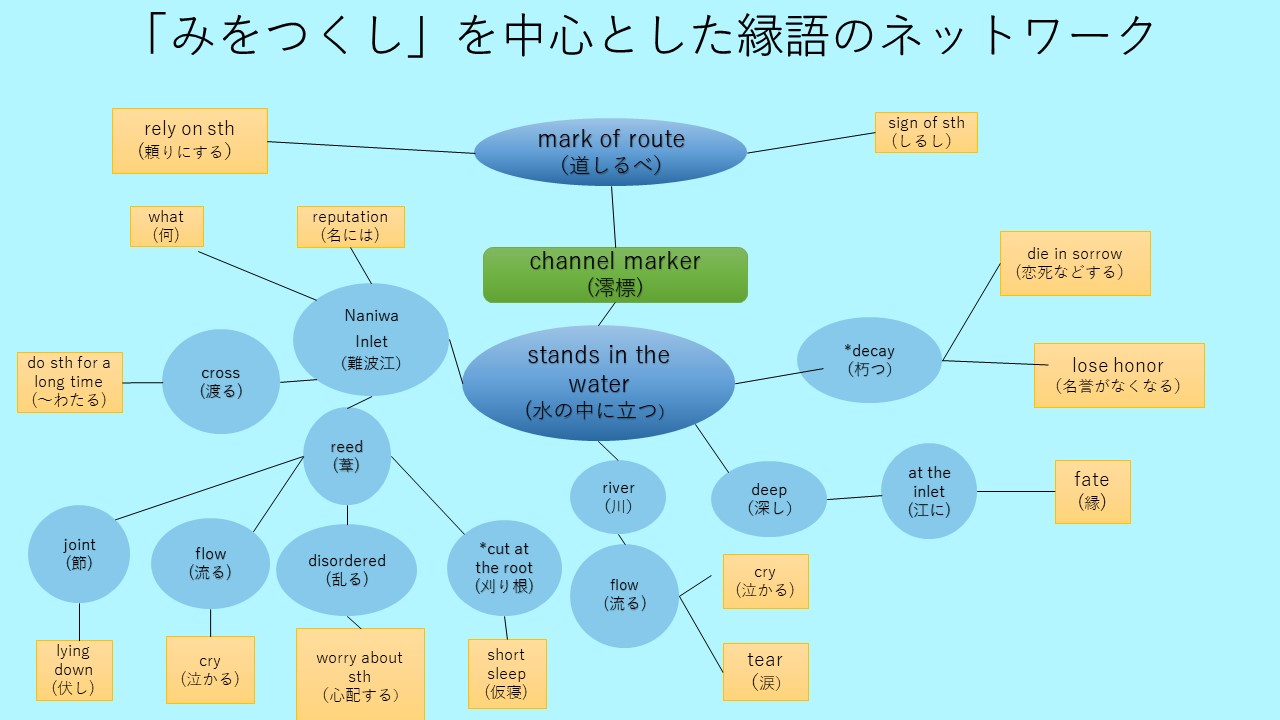

The formation of engo using kago with an associative relation

For the people in the Heian period, it is conceivable that a network of words was formed with primary and secondary associations to the conventional phrase, miotsukushi. For instance, looking in the “Encyclopedia of Japanese Waka Poetry [New Edition]” (a waka database) shows the attributes of miotsukushi are “mark of route” and “stands in the water,” and an associative relation is apparent to phrases including “Naniwa Inlet,” “reed,” and “rely on sth” (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: A network of associations centering on miotsukushi

*Expressions used in and after the 12th century

I attempted to translate using these associations (Fittler; bordered in red in Fig. 2). Since “Naniwa Inlet” and “cross” are linked in the network of “channel marker,” I used “across” as engo for miotsukushi in my translation. Engo, which are expressions specific to waka, can be used in this way, so there is no concern that the content will significantly stray from the original text as in previous translations. The word, “flow” in my translation of the poetic reply is associated with miotsukushi (channel markers) and Naniwa Inlet.

Looking ahead

How are the motifs recited in waka envisioned and written about in Western poetry? If there are motifs also common to Japanese kago, they can be utilized in translations, and I would like to verify them since they would also become topics of comparative research of cultures. In addition, the translation of Hyakunin Isshu (classical Japanese anthology of one hundred Japanese waka by one hundred poets) that I am working on with my Hungarian colleague is slated to be published in Hungary in the latter half of 2022.

Coverage/Constitution: Yuko Inoue

Cooperation: Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University, J-School