My interest in Thai politics was the starting point of my political research.

I am specializing in the field of comparative politics, which deals with domestic political phenomena. I am particularly interested in regime change, social movements, and hereditary political institutions such as monarchies. My current research theme is monarchies. A monarchy is essentially a ruling system headed by a hereditary head of state such as an emperor or king; Japan, with its emperor, is also a monarchy. There are two types of monarchy, depending on the role of the monarch: absolute monarchy, in which the monarch is actively involved in politics; and constitutional monarchy, in which the monarch is a symbolic figure and the parliament conducts politics in accordance with the constitution.

By definition a monarch in a constitutional monarchy is assumed to have little political power, but I do not think that definition is precise. From the outset I felt it was strange that in political science there is only very limited interest in unelected political actors (e.g., individuals, groups). That led me to conduct research on what kind of authority constitutional monarchs have.

It was my interest in the politics of Thailand that led me to pursue a career in political science. I traveled to Thailand with my family when I was in elementary school, and I had the impression that the people were kind, the climate was nice, and the country was peaceful. However, when I was in high school, a military coup took place in Thailand, and I was very surprised at the gap between my impression and what was happening there. From that point on, I became interested in Thai politics and eventually expanded my research to include politics in other countries too.

Measuring the strength of the powers given to the monarch in a constitutional monarchy

Monarchies were long a common form of governance in Europe and elsewhere. However, with the end of World War II, many countries abolished their monarchies and transformed into republics. Currently, there are about 45 monarchies left in the world, of which 35 are considered constitutional monarchies.

In my previous research, I examined theoretically how political power is divided between the parliament and the monarch. It is often thought that monarchs in constitutional monarchies are not given significant political powers, but the reality is different: the King of the Netherlands can appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister; the King of Belgium can suspend Parliament; and the kings of Bhutan and Liechtenstein have the power to veto bills.

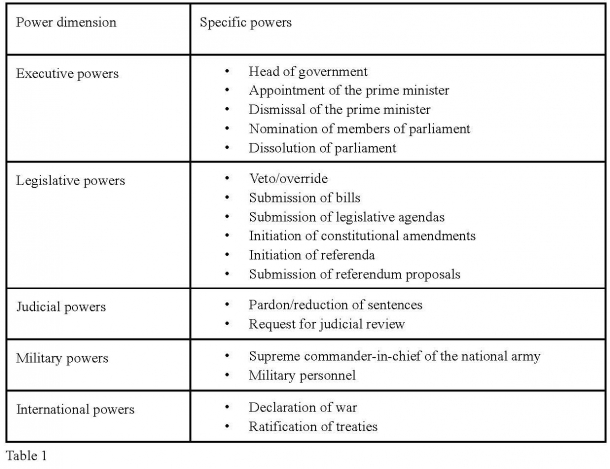

In that light, I am currently working to classify the monarchs of constitutional monarchies in terms of their power and the conditions under which they exercise that power. The American CIA publishes an annual compilation of information about countries around the world; I have selected 17 countries designated by the CIA as constitutional monarchies or parliamentary monarchies (countries where the monarch’s power is limited by the constitution and political leadership is exercised by the parliament or cabinet). I divided powers explicitly granted to the monarch by the constitution into five dimensions: executive power, legislative power, judicial power, military power, and international power. In Table 1, each category of power is assigned a value according to the strength of that power.

Table 1: In this characterization of the existence and strength of a monarch’s power, a value was assigned for each of the 17 powers specified in the constitution.

Taking the example of the power to dismiss a prime minister, the following values were assigned, ranging from most powerful to least powerful: 3 for “the monarch can dismiss the prime minister freely”; 2 for “the monarch has limited power to dismiss the prime minister”; 1 for “the monarch can dismiss the prime minister only with the consent of other political actors”; and 0 for “the monarch has no power to dismiss the prime minister or there is no provision for it.” In addition, for items that can be divided into yes and no categories: a value of 1 is assigned for a yes score for “he/she is the head of the government”; and 0 for “he/she is not the head of the government.” Using that rubric, I scored all executive, legislative, judicial, military, and international powers and tabulated them by country.

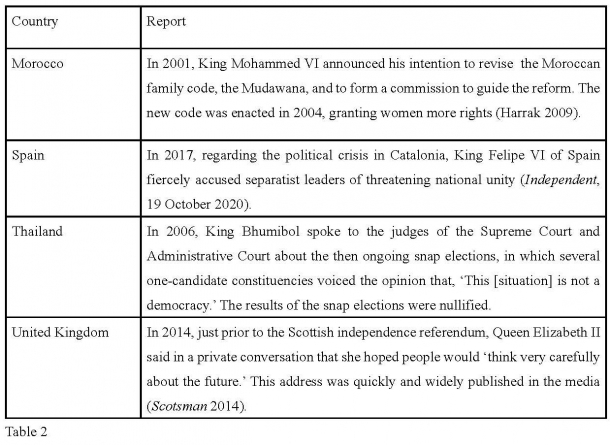

In the case of Thailand, the total score in the executive category was 3 and the total score in the legislative category was 1, indicating that the explicit powers given to the king under the constitution are very limited. However, those familiar with the situation in Thailand may find that result unexpected. In fact, the King of Thailand has been seriously involved in politics, having vetoed bills and vetoed a coup. It can be assumed that the reason for this discrepancy is the intervention of the monarch beyond the discretion given by the constitution. Further investigation revealed that intervention by the monarch beyond the constitutional authority exists in other countries too (Table 2).

Table 2: Examples of monarch interventions beyond the scope of the constitution

A continuous view of monarchical institutions

It is widely thought that constitutional monarchies are governed by a constitution and the monarchy is primarily symbolic, but my research has shown that this is not exactly the case. Although the situation varies from country to country, in a constitutional monarchy the monarch has various constitutional powers and sometimes even intervenes beyond the constitution. In other words, it is difficult to simply divide monarchies into constitutional and absolute monarchies; I think it is necessary to view the situation as a continuum between the two political institutions. In the future, I plan to broaden the scope of my research on monarch powers to include absolute monarchies.

References

- Harrak F (2009) The history and significance of the new Moroccan family code. Working Paper Series (No. 09-002). Institute for the Study of Islamic Thought in Africa (ISITA).

- Lester D (2020) Spanish Republicans protest for prosecution of former king Juan Carlos who fled country. Independent, 19 October. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/spain-protestsjuan-carlos-king-felipe-corruption-b1134625.html (accessed 10 November 2020).

- Scotsman (2014) Queen hopes Scots voters ‘think carefully’. The Scotsman, 15 September. http://www.scotsman.com/news/uk/queen-hopes-scots-voters-think-carefully-1-3541591 (accessed 1 December 2017).

Interview and composition: AIMONO Keiko

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School