How I Design Research to Investigate Culture Systematically

It is estimated that today there are 7,000 ethnolinguistic groups that exist in the world. Given that each has its own culture, how can researchers systematically investigate the culture of these groups? To enable comparison I first identify quantifiable attributes from numerous dimensions of culture. I often focus on language in my work. Language is one of the most important dimensions of culture, relatively easy to quantify, and has been used in studies that employ quantitative methods in many fields of social science, including political science, sociology, anthropology, and linguistics. In the literature on nationalism, scholars typically use the traditional method of comparing a few (or a handful of) cases to explore how ethnic groups build distinct institutions or win territorial sovereignty. Although these studies are sophisticated in historical analysis and theoretical nuance, they are limited in terms of external validity. To fill this gap, I rely on quantitative measures in my doctoral and ongoing research. This approach not only allows me to study a larger number of cases but also helps me investigate a crucial question in political science: why are some ethnic groups able to use their cultural attributes as an instrument of politics more effectively than others?

Why Language Is a Crucial Dimension of Culture

Of these 7,000 ethnolinguistic groups, only a subset has been able to rationalize their cultural practices, which include a standardized tongue, and have a sovereign state of their own. (Today’s world is composed of around 200 states.) The Japanese belong to this select group. There are many more groups that may have distinct cultural institutions but do not enjoy an independent state. Most groups do not even have standardized (or written) rules about how to practice their culture.

What explains this variation? In one of my papers published in the Journal of Economic History, I hypothesize that ethnic groups have to rationalize their cultural practices and tradition, ideally in an intelligible and easily-replicable—that is, written—form, to pass them down from one generation to the next and to ensure survival. Language plays a critical role in this process. The oral-based transmission of tradition is cheap and requires little technical skills for the users, but it is a risky and ineffective method as it is susceptible to extinction through devastating events including war, natural disasters, and diseases. If ethnic groups instead rely on written-based methods, leaving the legacy is easier; subsequent generations can use them to revive the language and other cultural practices by studying and improving on the written record. In this paper and as I explain below, I demonstrate how stateless ethnic groups use the technology that facilitates record-keeping to standardize their vernacular and consolidate their cultural practices. Based on a new data set I make, I undertake statistical analysis and draw implications for how they construct and maintain a unique group identity.

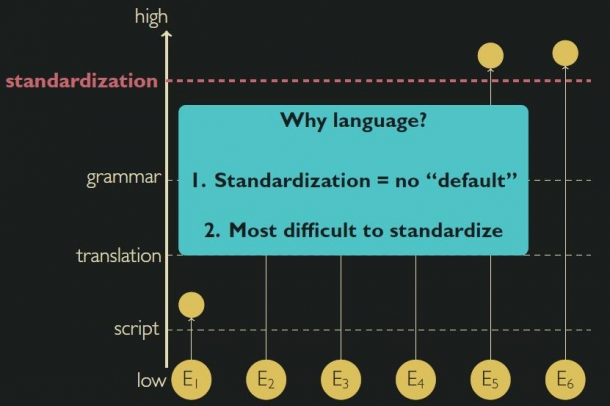

The outcome that I seek to explain in this paper is the occurrence of language standardization. To measure language standardization, I construct several benchmarks based on the historical evolution of language. For instance, ethnic groups may begin to write down their speech (see “script” in Figure 1 below). Many groups passed this stage, so the hurdle is set low. Of these, some invest more in their tongue by translating famous books written in established languages such as Latin or ancient Greek (“translation”). Fewer groups put in further efforts by devising a set of rules about how words should be organized to compose sentences (“grammar”) and how words should be spelled (i.e., orthography), or by studying where their words come from (i.e., etymology). As visualized in Figure 1, a language may be considered “standardized” when all these steps are complete. In the paper, I use the first publication date of vernacular dictionaries as a proxy for language standardization.

Figure 1 caption: This slide shows the condensed process of language standardization. The indicators on the left, such as “standardization” and “grammar,” represent the difficulty of achieving them in the process for ethnic groups. I hypothesize that the higher the bar, the more difficult it is for ethnic groups to achieve it and the fewer their number.

Print Technology as a Main Driver of Language Standardization

I focus on the printing press as a main driver of the mechanism of language standardization. In Europe, Johannes Gutenberg invented the first metal movable-type press around 1450 in the German city of Mainz. Previously, book production was based either on manuscript or on woodblock printing. Neither is an efficient method. The Gutenberg press was revolutionary in that it allowed for book printing in a much cheaper and faster manner. In the incunabula period of book production between 1450 and 1500, the price of the book dropped by two-thirds. Print technology spread throughout Europe quickly by early-modern standards: More than 110 cities had a press established by 1480 and the number grew to over 240 by 1500. As economic historians indicate, the single most important consequence that the press brought to bear was to reduce the cost of access to information. Lowered access costs also reduced the cost of becoming literates. Drawing on the literature on history, cultural sociology, and anthropology, I hypothesize that the adoption of the printing press has a positive impact on an ethnic group’s chances of codifying their vernacular.

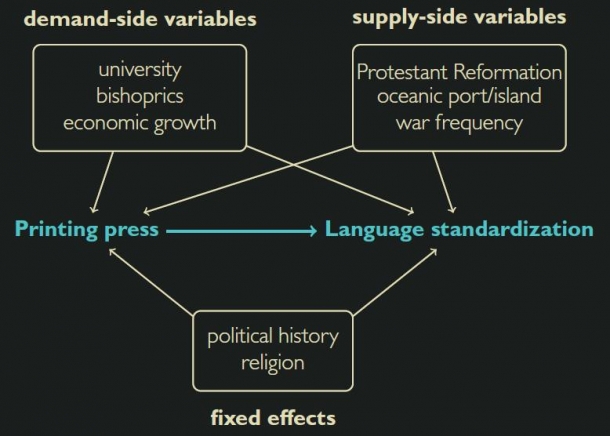

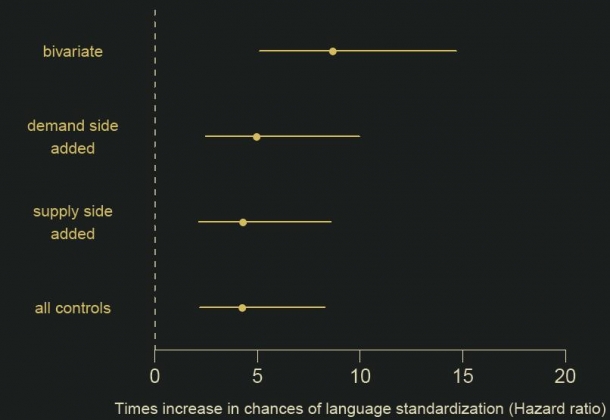

To test this hypothesis, I construct a new data set of 171 European ethnic groups from 1400 to 2000 and conduct statistical analysis. My statistical analysis controls for factors that may jointly determine the adoption of the press and language standardization, such as, inter alia, the founding of a university, the presence of bishoprics, economic growth, the Protestant Reformation, war frequency, and the access to the oceanic coast (see Figure 2). A key finding is that the adoption of print technology is positively and statistically significantly correlated with the chances of language standardization.

Figure 2 caption: This slide summarizes how my main hypothesis, shown in green, may theoretically be affected by other factors as represented in the “demand-side variables,” “supply-side variables,” and the “fixed effects.”

Figure 3 caption: This slide shows the result of my statistical analysis using event-history models. The dots represent the point estimates; and the horizontal bars, 95-percent confidence intervals. The numbers on the x-axis mean times increase in the chances of language standardization. The four models on the y-axis indicate different specifications. For example, in a fully-specified model (“all controls”), those ethnic groups that adopt the press have approximately five times greater chances of language standardization than those that did not adopt the press.

Exploring the Frontiers of Nationalism Studies

My current research builds on this paper to investigate how language rationalization on the state level affects economic growth in premodern Europe. In particular, in a new paper I focus on how the timing of the establishment of the grammar of the main vernacular of a society may assist growth-enhancing activity. I seek to contribute to nationalism studies by combining social-science methods with substantive questions.

Interview and Composition: Chisato Hata

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School