From animal archeology to HAI

Pic. 1: A scene from fieldwork in Mongolia. Migration and following pasture on horseback is frequently required

When I became a graduate student, I was interested in animal archeology, particularly research clarifying the relationship between people and animals from animal bones excavated from ruins. A turning point for me was when I first visited Mongolia in the summer of 2004 for site excavation and research. During this time, I investigated the bones of livestock animals that were killed and buried together in an ancient tomb. What rather astounded me during this time was the dense local nomadic culture, which lasting centuries, as attested by the interaction between the nomadic herders and their livestock that was actually occurring in front of my very own eyes. For this reason, my research theme shifted from the past culture to the relationship between the people and their animals occurring in the “present.” How animals became domesticated and how such domesticated animals changed people’s behavior – the oppositional mutual relationship – Human-Animal Interaction (HAI) – became the basis of my research.

My Encounter with Eagle Hunters

My fieldwork in Mongolia became very active from 2010. Initially, I lived for a total of about more than 400 days with Kazakh nomads in a small village called Sagsai in Bayan-Ölgiy prefecture. It locates about 1,500km to the west from the capital Ulaanbaatar, conducting investigations into such various topics as livestock ecology and ethno-ornithology (Pic. 1).

Pic. 2: The oldest eagle hunter in Altai, the now-deceased Komalkan |

Pic. 3: A young eagle hunter I had lived with (who was 19 years old at the time) |

One of the main research topics at the time was the culture of hunting with golden eagles on horseback so-called “the horse-riding eagle falconry”, an over 2,000-years of long tradition. Kazakh eagle hunters tame female golden eagles for hunting (Pics. 2–3). They tame large-scale raptors with wingspans longer than two meters, which prey mainly on mid-sized quadrupeds such as foxes. Foxes are hunted for their fur, which is indispensable for surviving a cold winter with temperatures as low as -40 Celsius. However, many procedures, as well as the knowledge and skills that come from experience, are required for training a golden eagle. Furthermore, a fresh supply of meat is required, equating to 9–12 head of sheep/goats per year. This is almost equivalent to half the meat consumed annually in a general household. In addition, the success rate of hunting is by no means high. When I investigated from 2011 to 2012, they spent a total of 41 hours over 10 days of hunting and caught only one fox (Pics. 4–5).

So why do they go through all this trouble to hunt? What I saw while living with the Kazakh nomads is that hunting with eagles is necessary for the Kazakh people to maintain smooth human relationships within the community, rather than for financial reasons. In the village, people do not go hunting with eagles alone. The hunt is conducted collaboratively with the accompanying eagle master and a beater. For example, when a young person starts hunting with eagles, it serves as an opportunity to get to know someone from a different generation within the community, including a senior member and a veteran, instigating communication between them. The fur that is obtained is used within one’s home, as well as used as gifts. In the world of nomads in which “knowing people” holds significance, the true essence of the horseback culture of hunting with eagles is maintaining a favorable social relationship while obtaining fur. It could be seen as a form of cultural resilience that was not lost despite the passing of several centuries.

Pic. 4: A scene from eagle-hunting. The mountainous region during the winter season drops to minus 40C. |

Pic 5: Training a golden eagle to capture a fox |

Eat everything and use everything! Survival tactics learned from the nomads

The life of a Mongolian nomad involves produce from five breeds of domestic animals: sheep, goats, horses, cows, and camels. Livestock are the assets of the nomads; they provide food, and pelts and string made from fur become the raw materials for their clothing and tents. Animal excrement is used for fuel in the nomads’ ovens to protect them from the cold and for flooring material within the stable, and it is also used for blocks and wall material of a fixed house. A unique strategy of theirs includes mixing horse feces with concentrated feed to be used as an emergency feed for cows, sheep, and goats during the winter season. Since horses selectively only eat the tip of a pasture that is rich in nutrients, horse feces are said to include plenty of undigested nutrients.

Another pillar that supports the Kazakh nomads’ dietary habits is dairy products. Various food items, such as cream, skim milk, butter, yoghurt, whey, sour milk (alcohol), and cheese are produced from milk. This signifies how a system of complex usage and processing of dairy is set in place, in which one form of produce becomes a material and an additive for another form of produce. This system can be described as “making complete use” of the produce, creating no excess waste.

When living in a land that does not produce many crops, in addition to livestock, the nomads also use Siberian marmots, wolves, grouse, and crickets in the wild as their food sources (Pics. 6–7). They are food sources that are widely believed to have nutritious and disease-prevention effects. For example, dissolving a wolf brain in hot water and drinking it is said to prevent migraines and sucking out cricket intestines and eating them is believed to be effective against atopic eczema. Furthermore, snow leopard meat was once eaten and was believed to be effective against 72 types of diseases. It was also believed that having the children eat the meat would make them immune to measles. Insatiable exploration of edible meat and beliefs that are similar to superstition are still deeply rooted in the lives of the nomads.

Pic 6: Wolves are often captured for food. They are eaten after they are raised to around the age of six months. |

Pic 7: Siberian marmot “Tarbagan” is a summer grassland delicacy. Whole roast (bodog) is said to be delicious. |

The life of nomads as seen from quantitative data

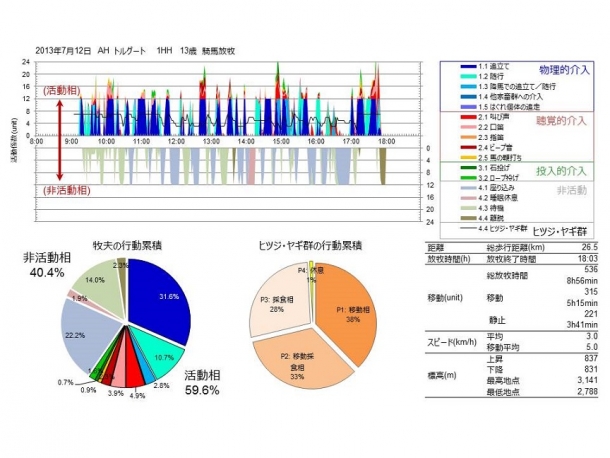

“Quantifying” the livelihood of the nomads is an extremely important task within my research. For example, herders walk a long distance, following their livestock, in their daily grazing tasks. In such investigation of the dynamism in their daily lives, I conducted my research by placing a GPS logger around the necks of the sheep and the cows, as well as asking the herder to wear a GPS or a physical activity meter. Behavioral analysis charts and actographs based on this data (Pic. 8) showed that the grazing period of the herder can last as long as 9.43 hours, with the total distance travelled reaching 34.6km. Furthermore, sheep and goats travel 16.7km on average every day, looking for pasture.

Pic 8: Daily grazing activity analysis using an actograph

A day in the life of the women of a nomadic household is also a hectic one. Women aged 29 to 60 were asked to wear a physical activity meter to investigate their daily activity levels. The results showed that their daily (average) walking distance was 15.6km (23,673 steps), with 3,420kcal burnt through walking and physical labor. On busy days, this number exceeded 4,500 kcal. Compared to Japanese housewives, the nomadic women perform twice the physical labor. The daily activity level is extremely high, while the productivity is by no means correspondingly higher given the harsh living conditions the nomads face.

For this reason, in recent years, young people from nomadic households and the surrounding countryside have been moving away from their communities, which is becoming a serious social issue. The population outflow from regional areas is serious. The breakdown of communities due to population decline is occurring all over the world, but in nomadic communities in particular, physical tasks such as gathering livestock and caring for them (e.g., shearing), daily grazing, producing dairy products, seasonal migration, and weeding require both male and manual labor. Depopulation of young herders in local communities might destroy the nomadic community from the inside. The nomadic lifestyle may disappear from the world in 50 to 100 years. The quantitative documentation of their lifestyle (which I refer to as “quantitative ethnography”) has the possibility of recreating the footsteps and behaviors of Mongolian nomads, which may disappear someday, in the future by using the data.

The possibility of geographical field science

As seen here, nomads live together with animals, use limited resources to their full potential, and create their own rules to co-exist with animals and environmental resources. From such co-existing strategies, we can find the roots of environmental adaptability on human being that has been transforming extreme environments (anökumene) into own living spheres (ökumene). I am not “researching nomads.” Rather, my mission is to decipher “how people adapt to a severe environment” and “how the human being will survive and co-exist with the environment in the future” through research on the living strategies and environmental adaptability of nomads and people who live in extreme environments.

In recent ethnology and cultural anthropology, their focus is being placed on how a theory is developed by the data. However, I myself am an old-school fieldworker and place priority on raw data from the actual fields. By recording, visualizing, and quantifying previously unknown data, through on-site research, the research content can be delivered not just to researchers, but to many other people. The very activity of field science – heading to the actual site on your very own feet, listening with your own ear, touching with your hands, and seeing with your very own eyes – is the only empirical knowledge that can be obtained in the age of the information society via the internet, and therefore is also the practice for problem-solving.

Interview and Composition:Ayako Yamamoto

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School