A political and economic look at weapon selection

I specialize in political science. I have undertaken research focusing on war and postwar society in this field. I am currently researching wartime weapon selection.

Weapons can be broadly divided into two types: 1) conventional weapons, such as bombs and missiles, and 2) unconventional weapons, such as antipersonnel landmines, biological weapons, chemical weapons, and nuclear weapons. The purpose of conventional weapons is the physical destruction of targets. Conversely, it can be said that unconventional weapons cause major mid- to long-term adverse effects on human, social, and economic activity rather than causing physical destruction. Because the effects of unconventional weapons—such as making the land difficult for people to live on or increasing the risk of illness or death for residents who stay in the area—last for a long period of time, these weapons can be referred to as “dirty weapons” that contaminate their targets. The characteristics of all weapons can be interpreted as the combination of their degree of “destruction” and “contamination.” For example, in simple terms, conventional weapons would be low-contamination/high-destruction, land mines would be high-contamination/low-destruction, and nuclear weapons would be high-contamination/high-destruction.

What previous research exists regarding weapons? Discussion of the use of weapons and their resulting effects has primarily taken place within the fields of tactical studies, environmental studies, and medicine. Additionally, in political science, the national security-focused field of international politics as it exists today has focused on the development of nonproliferation regimes for unconventional weapons. However, to date, no research has dealt with the selection or use of weapons and the resulting effects from a political and economic perspective.

New war research stemming from an interest in the postwar period

Meanwhile, research about war has been conducted quantitatively, particularly in American political science. What the traditional theoretical framework has modeled is a process in which winners and losers are determined probabilistically and the winning side receives some sort of wealth. Although such research is useful in clarifying the cause of wars, I feel that it falls short of complete comprehension. War substantially changes the way people live in the postwar period. This is one major characteristic of war. Accordingly, I believe that it is also important to direct our gaze to the postwar period that political science has thus far neglected. The “pain” of the postwar period is mostly determined by how said war was fought. As such, I focused on how weapons were selected in wartime.

To answer this question, we have created a model using game theory. Using information from the answers derived based on the theory, this paper will introduce the intriguing correlation between weapon selection and industrial structure in targeted locations.

Certain victory or future resources—the theory-based logic of weapon selection

Game theory is a tool for analyzing strategic interactions. Wars are not made up of unilateral decision-making. Hostile actors anticipate the response of the opposing force as they decide what action to take. When making decisions, adversaries experience the dilemma described below. Here, we assume the existence of two actors that are at war, such as two countries, a government and an antigovernment organization, or a guerrilla group and the local people. Additionally, we assume that a valuable resource, such as oil, is present on the battlefield. Because the actor that is using a weapon to attack wants to obtain wealth after the war, it does not want to destroy resources. However, if the actor causes too little destruction, the other actor protecting the land can obtain wealth from the resource, possibly leading them to mount a fiercer attack. In other words, the dilemma is that prioritizing victory leaves no resource behind, while prioritizing preservation of the resource does not promote the enemy’s surrender.

Reflecting this logic, we found that the logic of weapon selection as deduced from game theory was closely connected to industry type and resource type on the battlefield. The chance of recovery or renewal, when an industry or resource had been destroyed, was an important deciding factor in weapon selection.

In countries or regions with a capital-intensive industrial structure that would take time to recover and feature high-tech industry or in locations that have nonrenewable wealth such as oil or mineral resources, destruction is difficult and the likelihood of contamination by dirty weapons rises. Conversely, locations that rely on labor-intensive industries, such as agriculture, that would recover relatively quickly tend to be exposed to destruction by conventional weapons rather than contamination because their wealth lies in renewable farmland.

Testing the model — the case of the Cambodian Civil War

When a model is created using theory, it must be tested with real examples. We used the example of the Cambodian Civil War to test our model. The civil war that raged in Cambodia took place primarily in the 1970s.

A certain pattern can be observed in the location of landmines and aerial bombings in the Cambodian Civil War. For instance, aerial bombing primarily hit eastern areas, while large numbers of landmines were buried in western areas, such as the present-day Pailin Province and Battambang Province. The general belief has been that this happened for two reasons: first, because aerial bombing by the United States military was concentrated in the East, where the border between Vietnam and Cambodia is located and, second, because western areas such as Pailin and Battambang became strongholds for the armed insurgents of the Khmer Rouge and because landmines were buried there.

However, we hypothesized that this pattern was also influenced by industrial structure, and therefore, we tested the theory. The industrial structure of 1970s Cambodia was incredibly simple; its primary industries were agriculture, the majority of which was rice cultivation, and the mining of gemstones, such as rubies and sapphires. Gemstones are primarily produced in the western areas, which lines up with the areas where large numbers of landmines were buried.

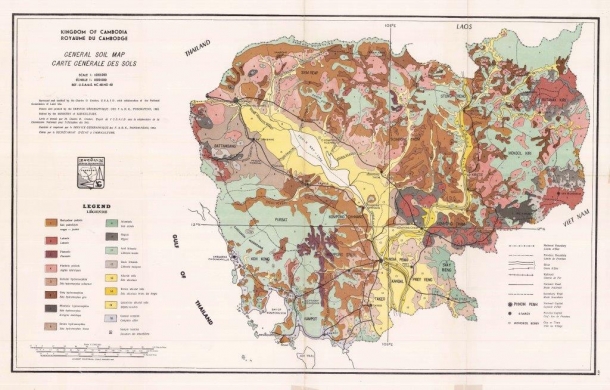

Meanwhile, areas with a thriving agricultural industry were heavily bombed. Figure 1 illustrates the results of a Cambodian land survey conducted in the 1960s. The yellow area on the map is the fertile region of the Mekong River basin, which is estimated to produce a large amount of rice. This region overlaps with areas that experienced heavy aerial bombing.

Figure 1: Results of Cambodian land survey (Crocker, Charles D. 1962. The General Map of the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Exploratory Survey of the Soils of Cambodia, Phnom Penh: Royal Cambodian Government Soil Commission/United States Agency for International Development)

Furthermore, we are also moving forward with model testing using statistical analysis. For instance, Figure 2 highlights soil ideal for agriculture under Cambodian government standards based on Figure 1 and lays a net referred to as a “fishnet” over the top of it. Soil ideal for agriculture is shown in green, while land without ideal soil is shown in brown. Each section of the mesh is six kilometers in all directions and each grid is characterized by the type of soil, areas of gemstone production, and types of weapons used there. We are creating many data points in this way and are attempting to statistically test the relationship between industrial structure and weapon type.

Figure 2: Classification map of Cambodian soil overlaid with a “fishnet” for statistical analysis (Created by: Waseda University Institute for Advanced Social Sciences, Assistant Professor Yasutaka Tominaga)

Although I am currently conducting research primarily using data on landmine usage in civil war, in the future, I would like to broaden the scope to include interstate war and other weapons, such as chemical weapons, to test a wide range of examples.

Moving toward human security

The goal of my research is to promote more effective evacuation of people from battlefields and to decrease the number of victims of war. Although it is difficult for social scientists to have their policy proposals accepted, I hope my research will contribute to human security and peace-building in the future.

Interview and Composition: Mariko Oshio

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School