The formation and transmission of the Buddhist scriptures

It is believed that Buddhism originated from the thoughts and words of Śākyamuni Buddha during the 5th century BCE, around 2500 years ago, and that his teachings were transmitted orally for centuries until they were finally written down.

The Buddhist scriptures were then both passed on to the Indo-Aryan languages such as Gāndhārī, Pāli, and Sanskrit and translated into the languages of the other regions to which Buddhism had spread, such as Chinese and Tibetan (Figure 1, left). Even after Buddhism became extinct in India, its scriptures persisted in the rest of Asia, and in recent centuries, they have been translated into many other languages, including European languages and modern Japanese.

The physical form of the Buddhist scriptures has also evolved from manuscripts to wood block printing, modern printing, and digital data (Figure 1, right).

Figure 1: The transmission of the Buddhist scriptures (left) and how their form has been transformed (right)

What is the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya?

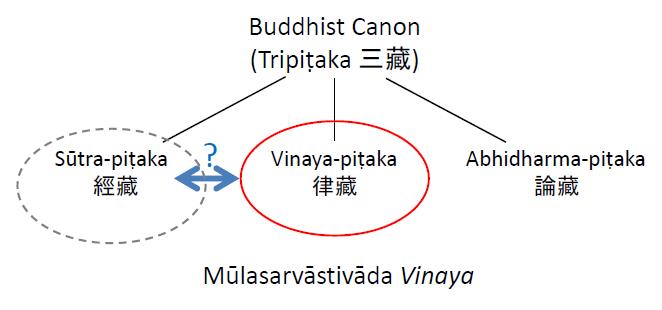

The Buddhist canon is known as the tripiṭaka (“three baskets”), consisting of the sūtra-piṭaka, the collection of teachings, the vinaya-piṭaka, which sets out the code of behavior for monks and nuns and the rules and regulations for monastic life, and the abidharma-piṭaka, which is concerned with interpretations and systematization of the teachings.

My research focuses on the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya, the vinaya-piṭaka belonging to the sect (school) known as the Mūlasarvāstivāda, which flourished widely both in India and elsewhere.

The extant substantial sets of vinaya material are from six schools, including the Mūlasarvāstivāda. In comparison with the vinayas of the other schools, the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya is voluminous. For example, I have translated a single chapter of the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya, the Bhaṣajyavastu, and the translation with footnotes included amounted to 600 B5 pages. This is only around 10% of the total.

The reason for this huge volume is that, in addition to the rules and regulations, the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya also contains far more sutras and stories than do the other vinaya. The regulations usually include episodic material, in the form “A monk did this bad thing, and the Buddha established a regulation forbidding it,” and in the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya these episodes are very long and go into great detail.

They also include frequent digressions, incorporating material not directly related to the regulations, and it is often unclear why these descriptions have been included.

Notwithstanding the extensive volume of its extant vinaya, most of the content of the sūtra-piṭaka of the Mūlasarvāstivāda has been lost. The objective of my research is to assemble the text of the sutras contained within the vinaya, with the aim of ascertaining the content of the lost sutras (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The relationship between the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya and its sutras. The vinaya includes many texts corresponding to the content of the lost sūtra-piṭaka (sutras).

Pieces of sutra remaining in a variety of forms

It has been known that the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya includes numerous sutras, and it is possible to reconstruct the lost sutras by analyzing this vinaya. However, the amount of material involved is so huge that no one has ever attempted an exhaustive study.

Among the very large number of extant Buddhist documents, some texts have been examined by numerous scholars, whereas others have scarcely been examined. Many sections of the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya have yet to be explored, and no one has attempted to assemble the sutras from these parts in a systematic way. It is this neglect that gave me the impetus to start this study.

The Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya exists as a Sanskrit manuscript, a Tibetan translation, and a Chinese translation, but these are not all complete (Figure 3). The Tibetan translation is close to a full version, but only around 80% and 30% of the entire body of the vinaya are extant in the Chinese translation and the Sanskrit manuscript, respectively.

Figure 3. Sanskrit manuscript (top), Chinese translation (middle), and Tibetan translation (bottom) of the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya

The degree to which the sutras are embedded in the vinaya also varies widely. In some cases, a sutra is named, and the full text is included, but in others, only the name is mentioned, and the actual text is omitted. It is often unclear where a sutra begins and where it ends in the vinaya, and in some cases, not only part of the text, but even the main subject of the story has been greatly altered in the process of its incorporation. Although such sutras can be viewed as “quotations” from the sūtra-piṭaka, this characterization is questionable, and there is no consistent rule as to whether it is the vinaya or the sutra that is being quoted. What is clear is that the same material is included in two different collections; in which case, it is more accurately described as “parallel material” rather than as a quotation.

Although the texts have fortunately been digitized, it is not possible simply to search for the same word and look for matches. The three versions must be read through and compared, but just producing a Japanese translation of the Bhaṣajyavastu was a four-year task. I am now engaged in preparing an English translation to make the results of this work available to scholars worldwide.

At the same time, I am also working on an analysis of the sutras included in another section of the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya, the Saṅghabhedavastu. Saṅghabheda refers to schism in the monastic community. The Saghabhedavastu includes both explanations of this and numerous biographical episodes relating to the Buddha and various other characters, including his cousin Devadatta who founded a different order.

When this is finished, I will proceed to the next volume. My current goal is to retrieve all the sutras embedded in the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya.

Interview and Composition:Ayako Yamamoto

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School