- Ryoji Matsuoka, Assistant Professor (October, 2014)

Disparities in Educational Attainment

My specialization is the sociology of education. Previous studies in Japan and overseas have found that one’s educational attainment differs depending on the family’s socioeconomic status (SES). If the parents are university graduates, for example, their children are more likely to also become higher education graduates. A high SES, however, does not automatically result in higher education attainment. For instance, the number of books at home (which is often used to indicate one aspect of SES) also correlates with academic ability as this can facilitate reading habits and positive attitudes toward school, thereby enhancing school performance. Like this example of the connection between SES and educational outcomes, I seek to illustrate the mechanisms that generate disparities in educational attainment. In this short essay, I discuss the results of nine empirical studies: three for each of the elementary, lower, and upper secondary education stages.

Analyses of Elementary School Students: Reading Habits, Parental Involvement, and Extracurricular activities

To identify the mechanisms that generate educational disparities in elementary education, I used data from the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. By statistically examining the relationship between the number of books (excluding comic books and magazines) read by first- to fourth- year elementary school students and by their parents, this study reveals that college-educated parents read more books and that their reading habits were related to the number of books their children read. In other words, the habit of reading was “inherited” from one generation by the next.

The second article analyzed whether parental involvement directly or indirectly structured children’s learning time outside school. The indicators of involvement included whether using shadow education services, the time spent watching TV or playing video games, and the time spent on parental monitoring of their child’s learning progress. Higher SES parents (e.g., college educated, and those with a higher household income) tended to be more involved in these forms of parenting. This study’ results also indicate that the amount of learning effort exerted by an elementary school student differs according to the degree of parental involvement, which was found to vary with socioeconomic status.

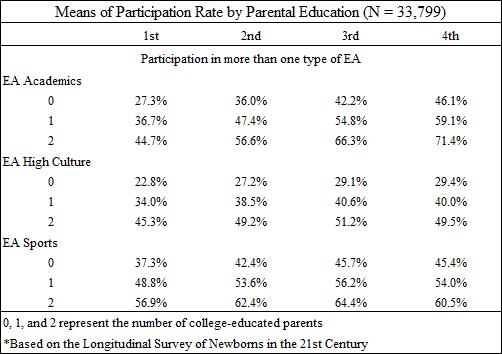

The third study examined adult-led extracurricular activities outside school as a source of educational inequality. The table below shows that children’s participation in extracurricular activities varied significantly with the educational attainment of their parents. This indicated that some children have more learning experiences outside the compulsory education system. In addition, it was found that participating in each of the three types of extracurricular activities—high culture (e.g., music), sports (e.g., swimming) and academics (e.g., cram schools and correspondence education)—facilitated a child’ emotional engagement in school. This means that gaps in learning opportunities outside the school system led to differences in the non-cognitive aspects evaluated at school.

Analyses of Junior High School Students: Teachers’ Expectations, Parental Involvement, and Deviant Behavior

To identify how family SES leads to disparities in educational attainment in lower secondary education, I used data on second year junior high school students (8th graders) from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). First, I assessed the teachers’ expectations of their students’ achievements and found that teachers had higher expectations for student achievement and assigned homework more frequently when a school’s SES (the average of the student SES at each school) was higher. Teachers’ levels of expectations were also related to the academic performance of students. While it has been pointed out that disparities between schools are smaller in the compulsory education system in Japan than in other countries, school SES (the average student SES) appears partly to differentiate the degree of teacher expectations for student achievement, which was related to the gaps in academic performance across schools.

Another study investigating parental involvement with TIMSS data found that higher SES parents tended to ask their children about what they had been learning in school more frequently and that the students of such parents demonstrated higher academic skills. Similarly, at higher SES schools, parents participated in school activities more actively, and this disparity in parental school involvement was associated with gaps in academic performance across schools. This means that, in lower secondary education, the parental involvement partly depends on SES levels in each field, home and school, and these disparities in parental involvement appear partially to account for the SES-based achievement gap.

Another study analyzing TIMSS data from Japan and the United States investigated deviant student behavior such as withdrawing from academic competition as a source of the gap in educational attainment. This study found that lower SES students were more likely to spend more than four hours watching TV or playing video games on a normal school day than their higher SES counterparts. At the school level, however, the average SES of the school was unrelated to this type of behavior which would not help students improve their cognitive academic skills. In comparison with the United States, known for an extremely wide gap across schools, the school’s SES was significantly associated with the deviant behavior. This was probably because public schools in the United States largely depend on local taxes for their revenue, and therefore, there are large gaps between the financially richer districts and poorer districts. In public schools in Japan, on the other hand, there is no statistically significant relationship between school SES and the deviant student behavior probably because the national government provides funds to reduce regional gaps in the quality and quantity of education. However, a gap in the behavior levels does exist between sectors in the compulsory education system in Japan; private and national junior high schools have far fewer students with the behavioral problem than their public school counterparts. These contrasting results from Japan and the United States indicate that education system structures differently affect specific student behavior that likely influence learning outcomes.

Analyses of High School Students: Shadow Education, Learning Time outside School, and Learning Competencies

For high school students, I analyzed data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). First, the data from 2006 indicated that students at higher SES schools tended to have additional lessons at shadow education institutions and spend longer hours studying outside school in the third month of the three-year high school education (10th grade). These results were obtained by controlling for the academic performance of individual students and schools hierarchically ranked based on academic levels. This meant that higher SES students performed better academically in the last year of lower secondary education, and thus they were concentrated at higher ranked high schools through the entrance examinations. In other words, because of the high correlation between student academic achievement and family SES, academic performance-based high school admissions lead to a socioeconomic segregation between schools. This in turn drives higher SES students in high SES/ranked high schools to prepare for higher education by attending cram (shadow education) schools and engaging in self-study in the third month of their three years of high school education

While there are students who exert learning effort right in high SES/ranked high schools, Japan ranks first for every subject among the 57 countries/regions examined in PISA 2006, in terms of the proportion of 15 year-olds who never study outside school. It was found that, in Japan, the percentage of students not studying at all outside school hours was larger in lower SES high schools. Lower SES students tended to attend lower ranked schools due to their relatively lower academic performance, and those who were not proficient at learning did not study at all outside school, it is probably because the schools did not expect them to go on to higher education. This was not observed in the United States with comprehensive high schools, since students are not sorted into different schools based on their academic achievement, and school SES is therefore unrelated to student study habits such as not studying at all outside school hours. As in the study on junior high school student behavior (i.e., watching TV/playing video games for more than four hours on a normal school day) in Japan and the United States, these results suggested that high school students’ study behavior differs according to the characteristics of the education systems.

Because it has recently been noted that non-cognitive abilities/skills are important in addition to cognitive, academic skills, I analyzed the relationship between SES and learning competencies, including the motivation to learn, using PISA data collected in 2009. I confirmed that higher SES students tended to have greater learning competencies at the time of the survey (high school freshmen, 10th graders). I also found that, even after controlling for academic skills, SES, and other factors, students with greater learning competencies participated more in additional learning opportunities and engaged more in self-study, thereby generating a positive cycle of learning habits on their own. This means that family SES appears to be the primary mechanism that generates gaps in both learning competencies and academic performance, leading to differences in educational attainment through factors such as student effort, learning opportunities outside school, and high school rank.

Creating an Education System That Maximizes Every Child’s Potential

The empirical results of these nine studies all indicate that SES-based educational disparities emerge by the time of the high school entrance examinations because of parental involvement, student learning behavior, and teachers’ expectations—all of which partly vary with the SES of the students and/or schools. This gap expands further in upper secondary education because of the socioeconomic segregation of schools through academic-performance based examinations, which unavoidably reflect the students’ socioeconomic family backgrounds. Though the compulsory education system in Japan is considered highly standardized, providing relatively equal opportunities to all schools/regions compared to other countries, I believe that improving public education should be the highest priority policy issue as a family’s SES cannot easily change and this is not their fault. As a scholar, I will continue to empirically illuminate as many mechanisms as possible as to how disparities in SES lead to inequalities in educational attainment, which could result in policy implications, in order to contribute to the creation of an education system that maximizes the potential of each and every child.

Interview and composition: Chisato Hata

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School