MIYAMA, Emily, Assistant Professor

Beginning My Journey in Southeast Asian Archaeology

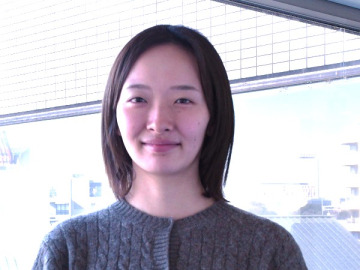

My research focuses on Southeast Asian archaeology, particularly on how maritime networks around the South China Sea took shape and developed from the prehistoric into protohistoric periods. My journey into the life of a researcher began in the summer of my second year at university, when my professor invited me to join a field survey. During my first fieldwork season in Vietnam, I encountered a type of prehistoric ornament known as lingling-o (Fig. 1, left photo 3), an artifact that would become a thread running through my work and Ph.D.

These earrings are broadly categorized into four main types, each distributed across the South China Sea region with subtle regional variations (Fig. 1, right, showing the distributions of types 2, 3, and 4). The most widespread type is a jue (玦)-shaped earring, characterized by a C-shaped ring with a slit (Fig. 1, left photo 1), which have been unearthed in China, throughout Southeast Asia, and Japan. Earrings with four projections (Fig. 1, left photo 2) are primarily concentrated in the northern part of the South China Sea during the Neolithic period, whereas those found mainly in the southern part include the earrings with three projections (Fig. 1, left photo 3) and the double headed animal earrings (Fig. 1, left photo 4). The earrings with three projections feature a rounded body with three sharply pointed projections, while the double headed animal earrings bear two animal heads set on opposite sides, each facing outward.

The widespread appearance of such distinctive styles across this broad region cannot be explained by coincidence alone. Recognizing that people had already been crossing seas and engaging in interaction more than 2,500 years ago, I became deeply fascinated by these earrings and by the human activities surrounding them. Nevertheless, no comprehensive, comparative study had yet examined these artifacts as a whole, despite their transnational distribution. To address this gap, I traveled across the region, visiting sites and museum collections, examining these artifacts directly, and compiling a detailed dataset on their form, size, and material composition.

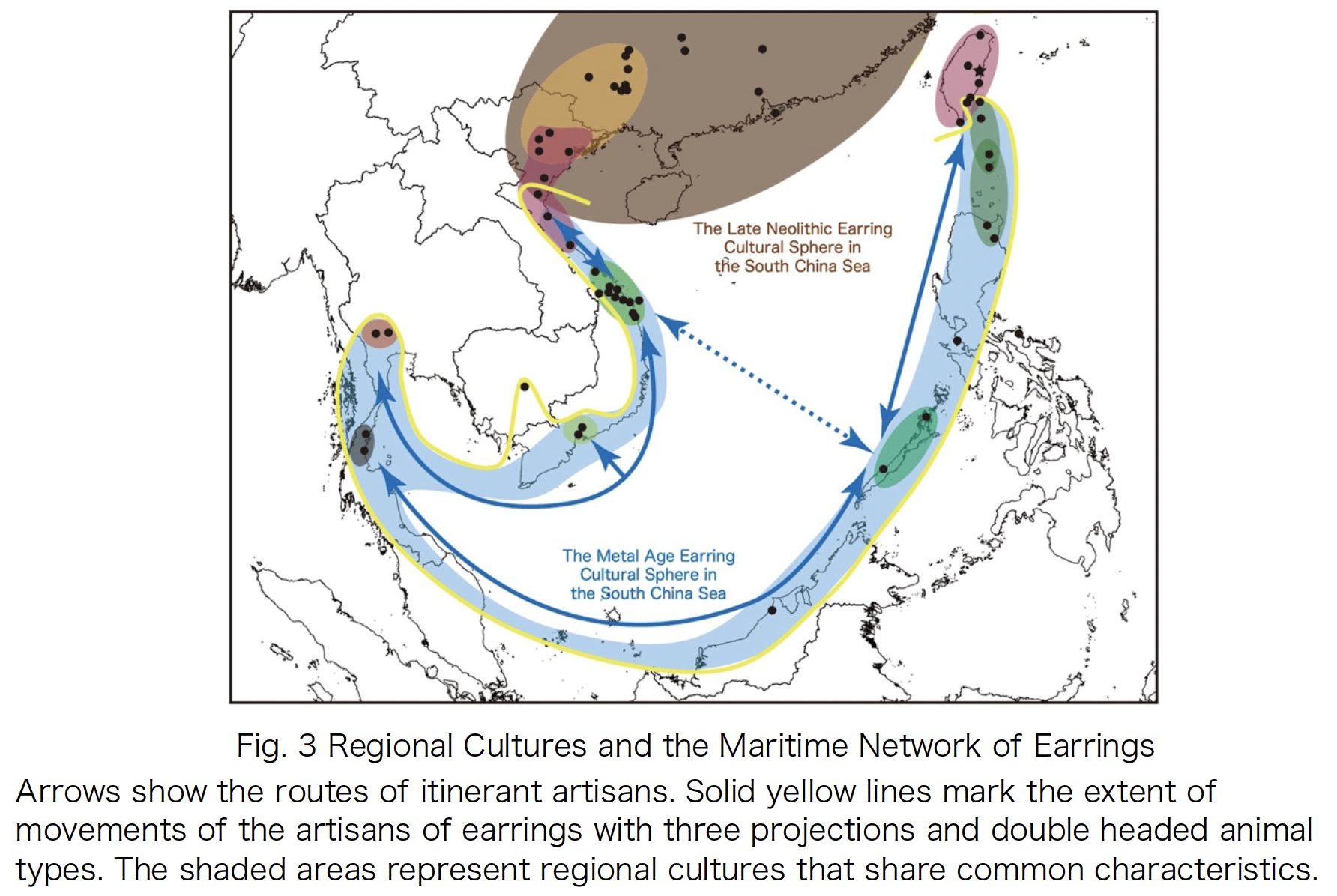

Over the course of many years through my undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral research, I devoted myself to these earrings. Ultimately, through the integrated analysis of morphology, manufacturing techniques, and raw materials, I demonstrated that itinerant artisans (mobile craft specialists) who moved between communities played a significant role in shaping the formation and expansion of maritime networks across the South China Sea (Miyama, Emily. (2021). Maritime Networks in Prehistoric Southeast Asia: The Ear Ornaments of the Southern Seas. Yuzankaku).

After earning my Ph.D., I embarked on a new phase of research focusing on petrographic analyses of the so-called Kalanay pottery, a ceramic tradition with shared characteristics found in the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. Through this work, I aim to shed new light on the dynamics of human mobility and cultural interaction in prehistoric Southeast Asia.

Previous Studies on Ear Ornaments and Maritime Network Models

In prehistoric Southeast Asia, people and objects moved freely across both land and sea. Bronze single-faced drums (Dong Son drums), glass and stone beads, and the earrings that form the focus of my research, are among the most representative examples of widely distributed artifacts.

Earrings have drawn scholarly attention since the earliest days of Southeast Asian archaeology. The first to conduct a systematic study was, perhaps unexpectedly, a Japanese scholar, Tadao Kano, who worked in Taiwan before and during World War II as both an entomologist and an anthropologist. As early as the 1940s, he proposed a model of cultural transmission from Vietnam through the Philippines to Taiwan, based on observed differences in the earrings projection forms. Following Kano’s disappearance near the end of the war, research on earrings came to a temporary halt. However, in the 1960s, numerous earrings were unearthed in the Philippines, renewing debates over whether they had been locally produced or introduced from elsewhere, particularly from central Vietnam, where substantial finds were already known.

As archaeological excavations increased, discoveries accumulated across the region, and a prevailing view emerged that placed the origin of these earrings with three projections and double headed animal earrings in central Vietnam, where they were unearthed in the greatest numbers. In the late 2000s, advances in compositional analysis, especially studies identifying Taiwanese nephrite, added a new dimension to this discussion. Using Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA), researchers identified zinc-bearing chromite as a characteristic inclusion unique to Taiwan nephrite. This finding demonstrated that nephrite from Taiwan had been widely circulated across what are now the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, revitalizing earring research and reshaping interpretations of interaction and mobility in prehistoric Southeast Asia.

On the theoretical side of maritime network studies, archaeologist Wilhelm G. Solheim II proposed the Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network, emphasizing that cultural similarities around the South China Sea resulted from the active movements and interactions of indigenous, sea-oriented peoples. In parallel, archaeologist Peter Bellwood, drawing on historical linguistics, advanced the hypothesis that Austronesian-speaking populations spread from southeastern China through Taiwan into Island and Mainland Southeast Asia. Within this framework, the widespread distribution of certain earring types came to be viewed as part of the broader process of Austronesian dispersal.

Where, then, were these earrings first conceived? How did their forms and materials spread throughout the South China Sea? And what kinds of human activities lay behind their distribution? These enduring questions have continued to guide my research on ear ornaments and the networks of people who produced and exchanged them.

Integrating Classical Archaeology and Interdisciplinary Approaches

As I examined earrings firsthand and gathered detailed information, I continually reflected on how human activities could be interpreted through artifacts, and what kinds of methods would best serve that purpose. Although many earrings appear strikingly similar in form, close observation revealed subtle individuality and recurring stylistic patterns. I came to understand that individuality reflects the variability of handcrafted work, while recurring styles derive from shared design conventions, manufacturing techniques, and material choices. Through this process, I realized that the study of these ornaments could reveal the “people who made the objects.”

Where there are makers, there are also users. As accessories, earrings likely served multiple roles, as personal adornments, as markers of social position or group identity, and as objects imbued with ritual or symbolic meaning. By examining their archaeological contexts and modes of deposition, it became possible to approach the “people who used the objects” as well. In this way, I began developing an analytical framework that addressed both the production and the use of earrings.

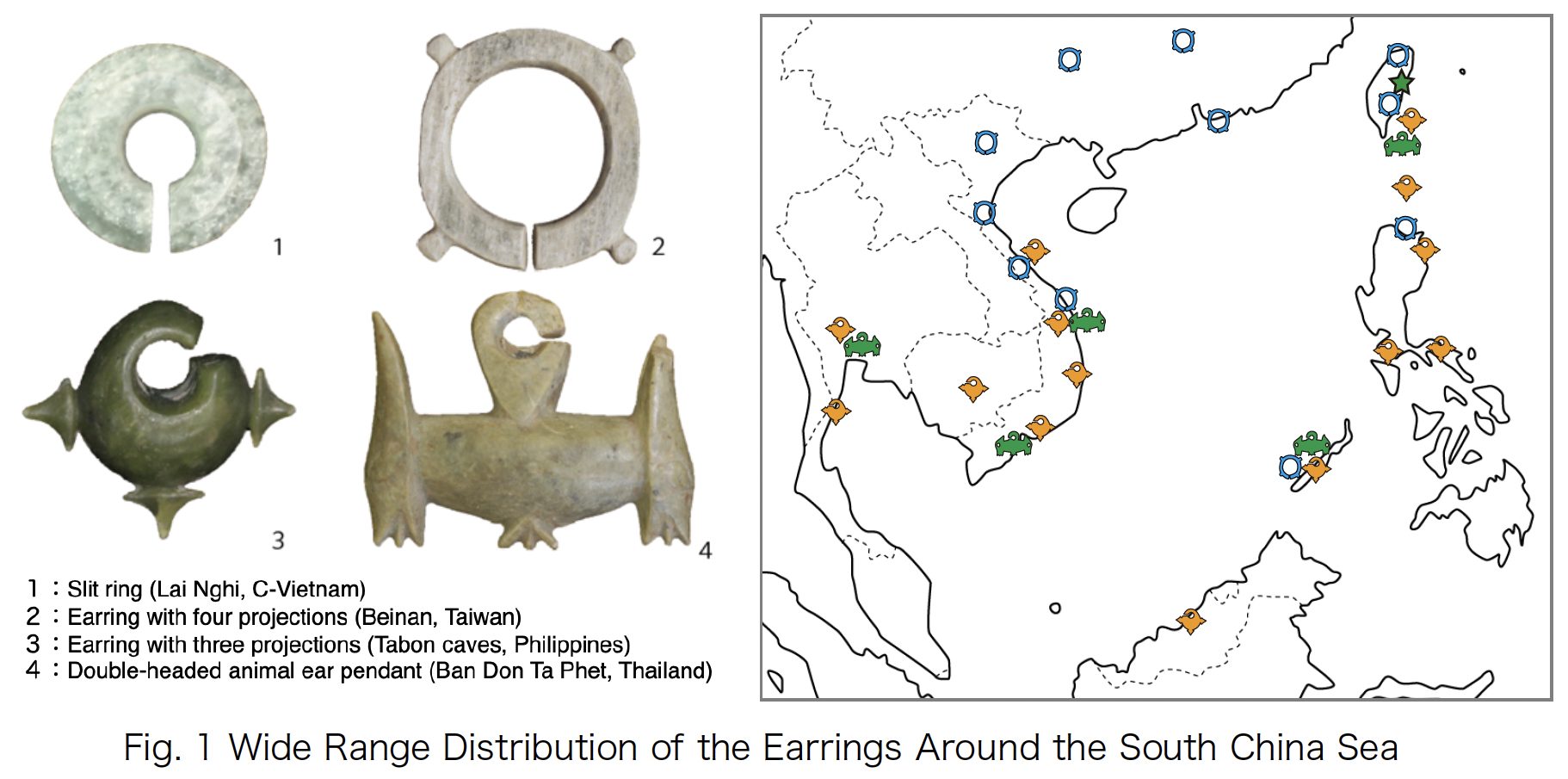

On the production side, I compared the features of morphology (design), manufacturing techniques, and raw material selection. I then proposed a new analytical concept: the production system. For morphological analysis, I drew on one of Japanese archaeology’s key strengths, typological classification. For technological analysis, I adopted the replica SEM (scanning electron microscopy) method, which involves taking impressions of tool marks and examining them under a scanning electron microscope to identify micro-traces of drilling, grinding, and polishing. For material analysis, I collaborated with specialists in the earth sciences, employing portable X-ray fluorescence (p-XRF) and SEM with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). The combination of these interdisciplinary techniques enabled me to identify groups of artisans who shared common design traditions, technical practices, and access to particular raw materials, and to trace both their similarities and changes over time (Fig. 2). As a result, my study demonstrated that the earrings with three projections, lingling-o, originated in the Batanes Islands of northern Philippines, while the double headed animal earrings first appeared in the Tabon Caves complex of Palawan in the southwestern Philippines.

On the usage (consumption) side, I analyzed the contexts of deposition and considered the social meanings attached to earrings in different regions. Earrings are most often found as grave goods, yet their placement within burials varies regionally. In southern Vietnam, they were sometimes still worn by the deceased; in central Vietnam and southwestern Philippines, they were placed close to the deceased, though it is uncertain whether they were worn or not; and in central Thailand, they were not worn but instead deposited within bronze bowls placed in the burial pit. These subtle variations reveal that mortuary practices differed from region to region. Moreover, within single cemeteries, fewer than ten percent of adult males and females were buried with earrings, suggesting that such ornaments served as selective symbols that marked particular ranks, identities, or social roles rather than as common personal adornments.

Through this dual perspective, focusing on both the makers and the users of earrings, it became possible to illuminate the presence of dynamic artisan communities that once animated the diverse societies surrounding the prehistoric South China Sea (Fig. 3).

Future Directions: Exploring Human Dynamics in Prehistoric Maritime Southeast Asia

Since the late 2010s, the concept of itinerant artisans has attracted increasing attention in studies of the production and circulation of ornaments, bronzes, iron objects, and glass artifacts. Consequently, research on widely distributed artifacts has entered a new phase. To understand the formation and development of maritime networks, scholars now consider not only exchange (as emphasized in the Nusantao hypothesis) and migration (as emphasized in the Austronesian dispersal model), but also a third mode of movement, itinerant artisanship, or the mobility of artisans who traveled between communities. This new perspective highlights that human movement in prehistory was far more multilayered and complex than previously understood.

In the next stage of my research, I aim to conduct integrative analyses of burial sites across the region, examining burial structures together with associated artifacts such as pottery, metal, stone, and glass artifacts, in order to identify diverse patterns of human mobility within and between maritime networks.

I also intend to explore whether a fourth mode of movement may be recognized beyond exchange, migration, and artisans’ mobility. Furthermore, I will investigate the social and economic perspectives behind these movements: what motivated people to travel, and how did different local societies receive and integrate newcomers, new materials, and new practices.

Through close collaboration with specialists in earth sciences, cultural anthropology, and related disciplines, I hope to reconstruct a more comprehensive picture of how people in the past connected across the sea, how materials were obtained and transformed, how technologies and ideas moved with artisans, and how communities negotiated change as maritime networks evolved. Ultimately, my goal is to shed light on the broader history and dynamism of past societies: how people, objects, and ideas moved through the maritime landscapes of the prehistoric South China Sea.