“Corrective measures” and alliance cohesion

US President Donald Trump consistently criticizes NATO allies, particularly European Union members, for failing to meet the alliance’s target of spending 2% of GDP on defense. In February 2024, while campaigning for a second term, Trump provocatively stated that in the event of a Russian attack on a NATO member who underspends on defense, he “would not protect you, in fact, would encourage Russia to do whatever they want.” (BBC World Service) He has also repeatedly called on Japan and South Korea to increase their contributions to American troops stationed in their countries to maintain security guarantees. While Trump’s rhetoric has been characterized as bold and arguably undiplomatic, such public criticism of allies is not without precedent. The Biden administration persisted in the American pressure on Asian allies and successfully negotiated increased Japanese financial contributions for troop stationing costs. Former President Obama declared that “free riders aggravated” him and initiated what he called “anti-free rider campaign” in Libya in 2011 “in order to prevent the Europeans and the Arab states from holding our coats while we did all the fighting.”(Atlantic Council a, b) Pressure on allies dates back to as early as presidents Eisenhower and Johnson, who urged key European allies to increase their contributions to the European Defence Community.

Although tensions surrounding defense burden-sharing and underspending within the Transatlantic alliance have been a focal point of both public interest and scholarly discourse, “defection” within a security community can manifest through diverse mechanisms as alliance “burden” extends beyond mere financial expenditures, encompassing multifaceted output measures such as deployable troop contributions, force commitment capabilities, and participation in collective sanction regimes. For instance, before the 2003 Iraq War, several members of NATO, notably Germany and France, not only refused to be a part of the military effort but also openly opposed the US-led intervention on a diplomatic front, leaving a deep rift within the alliance. In 2017, Turkey, a NATO member, decided to purchase the S-400 missile defense systems from Russia, a move that was deemed as potentially compromising the alliance’s security. Later, alliance solidarity was further tested by Turkey and Hungary’s deliberate impediments to Sweden’s NATO membership process. Moreover, European allies were adamant to join into American sanctions against Iran and China. (Brookings Institute, ECFR)

As these examples demonstrate, member states may strategically deviate from alliance commitments, potentially undermining the alliance’s cohesion and other parties’ strategic interests. In such instances, the stronger partner has several options: it can ignore these deviations—particularly if it decides not to risk the strength of the alliance—or it can adopt what I call “corrective measures” to reinforce compliance and deter other members from pursuing uncooperative policies. These corrective strategies encompass a continuum from rhetorical actions, such as public shaming and blaming, to tangible coercive measures such as sanctions or the suspension of military support.

Examination of the public preference for corrective policies

A critical determinant moderating the effectiveness of corrective measures is their perceived credibility, which is linked to the domestic political endorsement these measures garner in the sender country. When corrective measures lack popular legitimacy, the targeted state may anticipate and strategically exploit potential audience costs, thereby undermining the intervention’s potential efficacy. Conversely, corrective measures with robust public backing in the sender are perceived as more credible by the target and, consequently, carry enhanced diplomatic leverage.

In this research, I examine the public preferences of the alliance patron for corrective policies toward security allies that renege or underperform on their alliance commitments. More specifically, I explore the following question: What drives support for intra-alliance coercion among sender citizens? I advance three primary hypotheses: First, citizens of the dominant partner will demonstrate a preference for corrective measures against uncooperative allies, with a particular predilection for high-coercion interventions. Second, exposure to information regarding allies’ uncooperative behaviors will generate negative alliance perceptions and stimulate demands for reduced national contributions to the alliance. Third, contextual variables moderate citizens’ support for corrective measures, with lower support anticipated for allies with a democratic regime, substantial military capabilities, and with which the home country has a formal alliance treaty.

Multi-factorial vignette experiment

To empirically test my hypotheses, I conducted a pre-registered, multi–factorial vignette experiment in November-December, 2024. The experiment was fielded on the Qualtrics platform and involved a sample of 1,502 voting-eligible respondents in the United States. In the experiment, respondents were asked to evaluate a vignette about a hypothetical ally that randomly varied five attributes. The first attribute is the type of uncooperative action. The next three attributes manipulated the ally’s regime type, its military capabilities, and whether the alliance is based on a formal treaty. The fifth and final attribute, namely the US response, is the key independent variable. This attribute randomly conditioned five measures: terminating the alliance; public denouncement; adopting economic measures; reducing military support to the partner; and, finally, maintaining the status quo, which constitutes the neutral, ‘control’ condition. Afterwards, respondents were first asked to evaluate the US response, the primary dependent variable, and next, on their support for the US contributions to the alliance.

Important findings

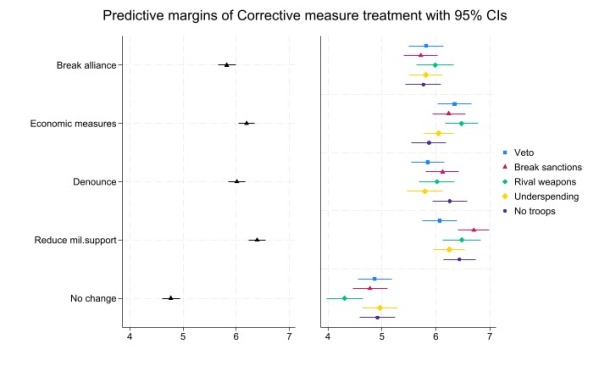

The empirical analyses reveal several important findings: One, the results strongly demonstrate that Americans favor any action over inaction. All four policies exhibit positive, significant, and sizable effects on policy approval compared to the reference category of “keeping the current policies without change.” American voters predominantly endorse coercive measures against uncooperative allies, with economic sanctions and military aid reduction receiving significantly greater support than rhetorical approaches, such as public denouncements (see Graph-1).

The x-axis presents the predictive margins of corrective measure treatment on policy approval with 95% robust confidence intervals. The right-panel plots the conditional effects across different values of uncooperative action treatment.

Second, allies’ uncooperative actions trigger demands for reduced American commitments, though public response varies considerably depending on the nature of the transgression. Notably, weapons procurement from rival countries such as Russia or China, or refusal to deploy troops for joint operations are perceived as more egregious offenses compared to financial underspending on defense. Third, the regime type of the uncooperative ally strongly conditions public support for adopting corrective measures, as the public is less likely to support measures against democratic allies. Conversely, neither the military capabilities of the uncooperative ally nor the existence of formal treaty arrangements with the United States exert statistically significant moderating effects.

Policy Implications and Conclusion

These findings carry substantial policy implications. With the second Trump presidency, there are growing concerns that US contributions to international alliances may decline significantly, while pressure on allies will mount to enforce more favorable burden-sharing arrangements. Indeed, the results of this study suggest that leaders may pay considerable domestic costs if they do not act against allies that behave uncooperatively, and consequently we may expect the US President to exert pressure on “underperforming” allies. For instance, defense contributions among NATO allies represent a particularly salient source of tension in transatlantic relations. The results of this study show that while voter sensitivity to defense underspending remains notably lower compared to other forms of alliance violations, the American public backs the strategy of exerting leverage on allies to contribute more.

Arguably, if potential violators of alliance commitments or “underperformers” anticipate retaliation from the dominant power due to strong voter expectations for active pressure, the mere threat of the use of corrective measures may discourage defection and strengthen alliance cohesion. At the same time, coercion against allies entails significant strategic costs and inherent risks. They can generate “psychological reactance,” stimulating feelings of defiance and resistance and potentially causing target states to reinforce their original positions. Moreover, external pressure mechanisms may catalyze rally-round-the-flag effects within target nations, enhancing leader approval, and, consequently, persistence of the wayward behavior. This is the reason why, despite their frequent use—against both foes and friends—and considerable costs, sanctions are seldom effective. On a grander level, corrective measures run the risk of straining relations and alienating partners and eroding mutual trust, thereby damaging long-term relationships with the target and compromising future cooperation. Consequently, leaders should carefully calculate the potential costs and benefits when considering corrective measures to influence ally behavior.