Do child marriage bans generate health benefits for the next generation?

Child marriage, defined as marriage where one or both of the spouses are under the age of 18, is widely recognized as a violation of human rights. Despite decades-long efforts, child marriage is a global problem that occurs across country, culture, religion and ethnicity. Globally, it is estimated that approximately 700 million women are married before their 18th birthday. If appropriate actions are not taken, an additional 150 million girls will marry before they turn 18 by 2030. Although numerous low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have legally banned child marriage, the eradication of this practice is currently far from becoming a reality. Eradicating child marriage is, thus, one of the main targets under the fifth Sustainable Development Goals since the persistence of this practice may generate further economic costs in the future by increasing population growth, various adverse health and development outcomes.

There is substantial causal evidence documenting that a delay in marriage age yields better education and labor market outcomes for women as well as better health and education outcomes for their children. Yet, many countries continue to document high rates of child marriage, for which the existing literature has explored a variety of economic and sociocultural explanations. For governments interested in eliminating the practice of child marriage, age-of-marriage laws are, perhaps, the most direct policy lever available. While many studies have examined the effects of these laws on the outcomes of women, there has been much less research on the effects of these laws on the health of the next generation.

I start up this research project with Associate Prof. Teresa Molina (University of Hawaii), Prof. Yoko Ibuka (Keio University), and Prof. Rei Goto (Keio Uiversity). We estimate the intergenerational effect of child marriage bans, which set a legal minimum age of marriage to 18, on mortality rates among children of the affected women. Existing work shows that child marriage bans improve women’s socioeconomic outcomes and delay age of marriage in some contexts. We also know, primarily from studies that use age of menarche as an instrumental variable, that delaying age of marriage leads to better outcomes for children. However, it is not clear whether and to what extent child marriage bans will improve child health, especially given that age of marriage laws are often not properly enforced and can sometimes lead to substitution away from marriage to informal unions. In addition, child marriage bans, when they are enforced, may have the unintended effect of making child brides more hesitant to seek prenatal or postnatal care (for fear of legal punishment), which could lead to worse health outcomes for their children. In short, it is not clear whether child marriage bans will generate health benefits for the next generation.

Calculate the pre-ban age at marriage and decreasing child mortality

For this analysis, we use the MACHEquity Child Marriage Policy Database, which contains information on child marriage bans over the period 1995 to 2012, to identify the timing of the bans in each country. This country-level dataset is then linked to the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), representative surveys of women aged 15-49 in LMICs, from which the main outcomes are extracted. Our final dataset includes 17 countries that legally banned child marriage under the age of 18 during the period from 1995 to 2012.

To isolate the causal effects of the bans, we exploit two sources of variation: subnational regional differences in the pre-ban age at marriage and variation across cohorts within countries in exposure to the bans. We first calculate a region-specific measure of treatment intensity, defined such that locations where, in the pre-ban period, the occurrence of child marriage was common and child brides married particularly young are considered to have high treatment intensity. It means that individuals in these locations should be more affected by a child marriage ban. The treatment intensity variable is then interacted with an indicator for cohorts exposed to the bans (i.e., individuals under the age of 18 at the time a ban was implemented in their country). If the bans reduce child mortality, then there should be a larger decrease from women who turned 18 before to those who turned 18 after a ban in areas with high treatment intensity compared to areas of low treatment intensity.

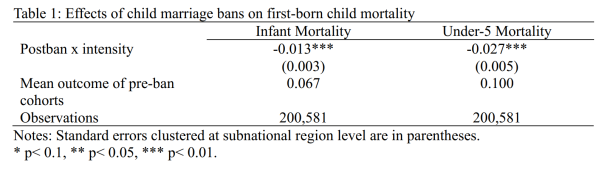

The bans have significant and sizable effects on infant and under-5 mortality

Table 1 reports our main results, showing that the bans have statistically significant and sizable effects on infant and under-5 mortality. Specifically, we find that a one standard deviation (SD) increase in treatment intensity reduced infant and under-5 mortality by about 0.95 and 1.97 percentage points, respectively (approximately 14.2 and 19.7 percent relative to the mean of pre-ban cohorts). Heterogeneous analysis indicates that the effects were driven by low-income countries and households with lower wealth. Our estimates are robust to various specification tests, including those that account for contemporaneous policies, differential trends due to regional characteristics, alternative samples, and migration issues. The pattern of our coefficients from a standard event study analysis, as well as staggered difference-in-differences designs, lends support to the validity of our empirical strategy.

Regarding mechanisms underlying the effects, our analysis shows that the bans appear to be reducing child mortality primarily by delaying age at first marriage and first birth. Age at marriage and first birth could both be important factors because a woman who goes into a marriage or into her first pregnancy with more maturity may have more bargaining power when it comes to securing health investments for herself during pregnancy and for her child immediately after birth. Women going into marriage or pregnancy with more maturity should have more agency and bargaining power, which are likely to be important for prenatal and postnatal health investments. We also find that child marriage bans led to a reduction in the share of mothers giving birth under the age of 18. This could be due to biological reasons. Specifically, in the medical literature, it has been suggested that the body of a teenager is still not fully developed and not optimal for the development of a successful pregnancy, and that lack of psychological maturity from mothers might lead to inadequate antenatal and postnatal health behaviors, which in turn affect child health. Neither increased maternal schooling nor employment rates appear to be important mechanisms in this setting.

To improve the health of the next generation

Findings from our study highlight the importance of evaluating large-scale policies with respect not only to their primary, targeted outcomes but also to potential downstream effects. Previous economic literature in developing countries has shown that education reforms and health interventions do not only have positive effects on the directly affected individuals, but also have intergenerational effects on health and mortality. Our study contributes to this large body of literature by revealing child marriage bans as yet another government policy that has the potential to improve the health of the next generation.