Beyond our grasp

I am a vision scientist — an experimental psychologist studying consciousness, human vision and language. I’m interested in how we process sensory information around us that is not conscious to us. For example, sometimes we have limited attention, so we can only pay attention to a small amount of information. What about the information that is beyond the grasp of our attention? When information doesn’t enter our awareness, what happens to it? Does it influence our behavior?

The main project I’ve been working on at WIAS is to understand how top-down information or top-down processes affect unconscious information processing. People used to believe that unconscious information processing is just automatic, somehow triggered by some random process in your head or in the environment. What I’m trying to understand is, how what we focus on affects such processes.

Neural basis of modulation in the brain

I have some initial work from my postdoc showing that the difficulty of a task affects how we process subliminal or unconscious information. I’m also interested in understanding the neural mechanism behind it. My collaborators and I scan our participants’ brains to find where the neurological basis of such a potential modulation is in the brain.

I’m doing this work in collaboration with National Taiwan University. WIAS itself doesn’t have a lab or experimental space, so I collaborate for the behavioral experiments with Professor Katsumi Watanabe on the Waseda campus. For the MRI experiments, I collaborate with Professor Brown Hsieh at National Taiwan University. I think that’s the core value of WIAS — you’ve got to branch out and collaborate.

Gap in the theory

I’ve always been interested in perception, sensation and cognition. In psychology we hear a lot of theories about how implicit a lot of information processing is, that it is automatic and beyond our awareness. When I was an undergrad, studying awareness or consciousness was not that acceptable. People treated it as an outlier. Memory, emotion and psychological diseases were studied a lot. But how we become aware of the sensory world — the attitude is that it is a subject fit for philosophy. But in textbooks or in class, people talked about it a lot without devoting energy or time to studying the topic. I realized that there was something lacking here.

Real-world applications

Driven by our studies showing interaction between attention and unconscious processes, ultimately, I want to develop a disease model to apply to real-world problems. We have all these hypotheses about how attention is regulated, and how we process subliminal information around us. We should be able to apply this to specific individuals, like people who have attention deficit disorder, or early–stage diseases.

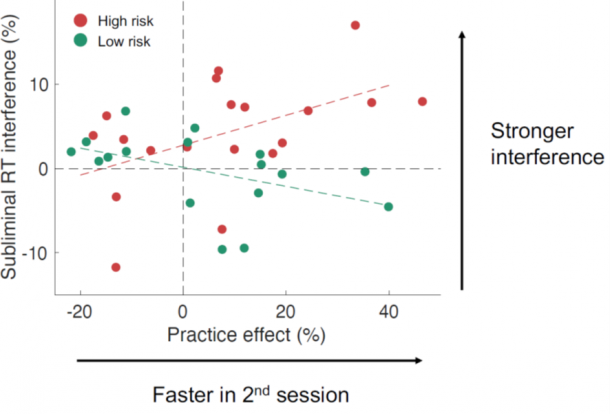

In our current study, our subjects were older participants, on average 75 to 80 years old. In our collaborator’s earlier work, an interesting thing is that if you look at how they use their attention with EEG, they actually show some differences, but that isn’t reflected in their performance (Fig. 1).

They may be working on the same task, but their strategy of using their attention could be very different. That prompted the beginning of our study. On the surface, judging by their performance, they’re all basically the same, but there may be some implicit deficit going on for people who have a high risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

This could lead to a major indicator that we could combine with the well-known biomarkers such as tau or beta amyloid. It might provide another very early biomarker or behavioral marker for diseases.

Fig. 1 Practice makes imperfect.

The more practice high-risk individuals have, the more interference they receive. This is our first evidence to suggest that they are using their attention in a very different way, maybe in a pathological way, because the more attention they have, the more they use this attention to process distracting information.

Probability tracking

I also study how we track probability unconsciously. For example, when you walk down the street and see a traffic light, it doesn’t just give you a color, it also gives you a probability — it tells you how likely you are to get hit by a car.

I’m fascinated by how our visual system tracks all this information around us. When you walk on a crossing in Shibuya, there’s no way you can look at all the lights and all the people around you. I’ve been wondering whether we have some sort of subliminal system that helps to track such information, the probability of the information around us, which is also predictive – it helps us to predict what’s going to happen next.

Japan connections

I was happy to be able to come to WIAS. I’ve always liked Japan. I’m fascinated by the culture, and I’ve had a lot of collaborators in Japan because we go to the same conferences and attend the same meetings. I heard some good things about the institute, so I talked to my postdoc supervisor, who is Japanese, and thought maybe this was a good career move to pursue. Things turned out to be great, and I’m enjoying my stay at WIAS very much.

Interviewed and written by Robert Cameron

In cooperation with the M.A. Program in Journalism, Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University