UNNO Noriko, Assistant Professor

My interest in Chinese Muslims

I am researching the modern history of the Hui people, sinophone Muslims living in China. The Hui are the descendants of Muslims from West Asia (e.g., present-day Saudi Arabia, Iran and Iraq) and Central Asia (including present-day Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan) who migrated to China between the seventh and 14th centuries. The Hui, an ethnic group resulting from interaction between the Han Chinese and Mongolians, speak the Han language (Chinese language) and are almost identical in appearance to the Han Chinese. Living mainly in the northwest region of China, they number about 12 million, accounting for about half of all Muslims living in China. They are recognized as an ethnic minority in China, where their population is large.

I studied abroad, in Finland, when I was in high school. I stayed with a family in a village where there were almost no Asians, so I often felt alienated. In that situation, I was treated very well by Muslim immigrants who were also minorities. As a result of that experience, I became interested in Muslims living outside the Middle East. Later, I learned that there were Muslims in China as well, and since I had always been interested in Chinese culture, I thought that if I chose “Muslims living in China,” as the theme of my research, I would be able to study both China and Muslims living outside the Middle East, so I decided to pursue that path.

It all started with one photograph

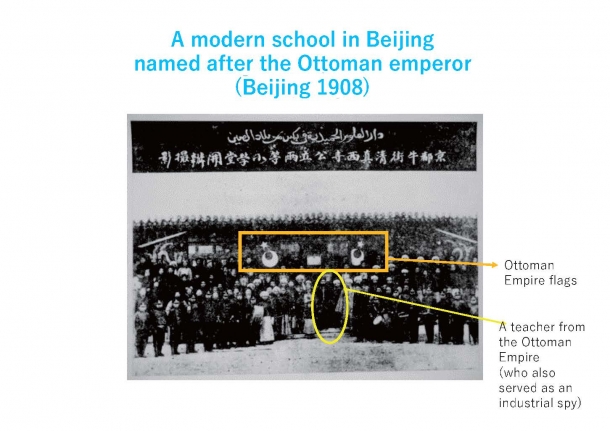

I have been reading about and analyzing the modernization, globalization, and political changes in East Asia from the perspective of Chinese Muslims (here, the Hui people). In my current research I am examining the role of Chinese Muslims in international relations and global history. In the midst of all my exploration, one photograph caught my attention: a 1908 photo commemorating the establishment of a modern school for Chinese Muslims in Beijing, a project supported financially by the Ottoman emperor (Fig. 1). I wondered why the emperor of the Ottoman Empire took the trouble to provide financial support for the Chinese Muslim minority in the Qing Dynasty, a country with which he had no diplomatic relations at the time. Subsequently, I decided to investigate the involvement of the Chinese Muslims in the two major empires of the East and West, the Ottoman Empire (later the Republic of Turkey) and the Qing Dynasty (later the Republic of China), in the early 20th century, when modernization was rapidly progressing.

Figure 1: Commemorative photo at a Chinese Muslim school supported by the Ottoman emperor.

Highlighted in the image: Ottoman flags and a teacher from the Ottoman Empire. (1908: Beijing)

Were the Ottoman Empire and the Qing Dynasty similar, with shared interests?

During the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, both the Ottoman Empire and the Qing Dynasty were in gradual decline after losing wars against the Western powers. As they struggled for survival and sought to modernize their industrial, military, political, and educational systems, they gradually became interested in each other.

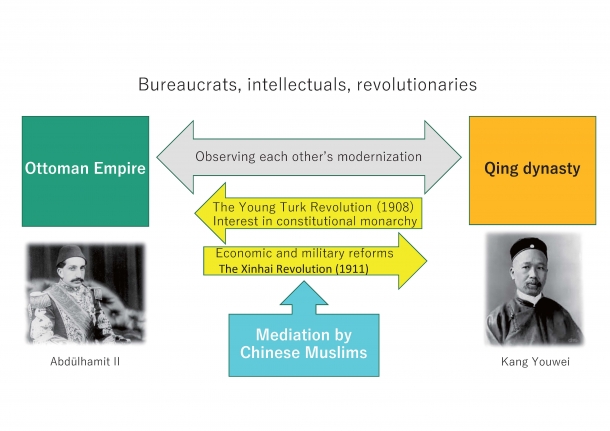

The Ottoman Empire was interested in the Xinhai Revolution, which led to the abdication of the Qing emperor, as well as the major military and economic reforms that were accomplished there in a short period of time. They attempted to send envoys to the Qing on several occasions, but encountered difficulties. They asked Chinese Muslims with whom they had some relationship to act as intermediaries in negotiations with the Qing. Through Chinese Muslim intervention they also sent spies to the Qing posing as teachers; one is shown in the photo in Figure 1. On the other hand, some Qing Dynasty politicians and bureaucrats were interested in the Young Turk Revolution that overthrew the tyranny of the Ottoman Emperor Abdülhamit II and prompted the movement toward constitutional democracy; it appears that they asked Chinese Muslims to mediate their visits to the Ottoman Empire (Fig. 2).

At that time, there was strong prejudice and discrimination against Chinese Muslims because of the Muslim rebellions that had occurred in various locations in the late 19th century. Qing Dynasty suppression was heavy. In order to break away from that situation, Muslim religious leaders took the lead in educational reform, aiming to raise the status of Muslims in the Qing Dynasty. Some Chinese Muslims paused at Istanbul (the capital of the Ottoman Empire) during their pilgrimage to Mecca to negotiate directly with the emperor for financial and humanitarian support for educational reform; some traveled to Japan to study and to learn from Japan’s rapid modernization after the Meiji Restoration. The network of Chinese Muslims expanded greatly from east to west.

Figure 2: The Ottoman emperor Abdülhamit II was interested in the Xinhai Revolution and the economic and military reforms in China. On the other hand, Qing dynasty politicians such as Kang Youwei were interested in the Young Turk Revolution and Ottoman movement toward a constitutional monarchy. It is thought that the mediation by Chinese Muslims was a driver of the progress of exchanges between the two sides.

Tentative conclusions

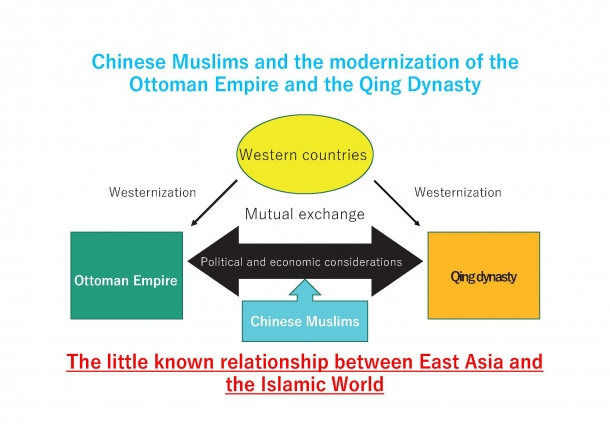

The modernization of the Ottoman Empire and the Qing Dynasty tends to be regarded as Westernization unilaterally imposed by the West. However, I hypothesize that Chinese Muslims, who mediated the interaction between the Ottoman Empire and the Qing Dynasty, may have had an indirect influence on the modernization of both countries (Fig. 3). At that time, countries including Japan, Germany, and France were also trying to make strategic use of Chinese Muslim connections to expand their influence in Chinese territory. In other words, the network established by Chinese Muslims in the East and West contributed to the modernization of the Ottoman Empire and the Qing dynasty; it could be said that at the same time it was being used for political reasons by Japan, Germany, and France. A close inspection reveals that intentions of various countries to skillfully exploit the underlying identity issues and survival strategies of Chinese Muslims living as minorities.

I plan to continue reading primary historical documents, with an eye to intelligence activities and international relations in countries around the world, in my re-examination of the history of Chinese Muslims from a broader perspective than that of earlier studies. At the same time, I would like to consider the role played by informal human networks in the modernization of Asia.

Fig. 3. Tentative conclusion: that Chinese Muslims may have had an indirect influence on the modernization of the Ottoman Empire and the Qing Dynasty.

Interview and composition: AIMONO Keiko

In cooperation with: Waseda University Graduate School of Political Science J-School