Pursuing optimal regional disaster countermeasures

“When it comes to regional disaster preparedness and mitigation, traditional measures are no longer effective,” says Professor Masaki Urano, a sociologist who studies optimal regional solutions as disaster countermeasures. The Great East Japan Earthquake has prompted us to reconsider society itself and ask questions such as, “What should we be aware of to be prepared for an event like this in the future?” We ask Professor Urano to discuss how to optimize regional disaster countermeasures.

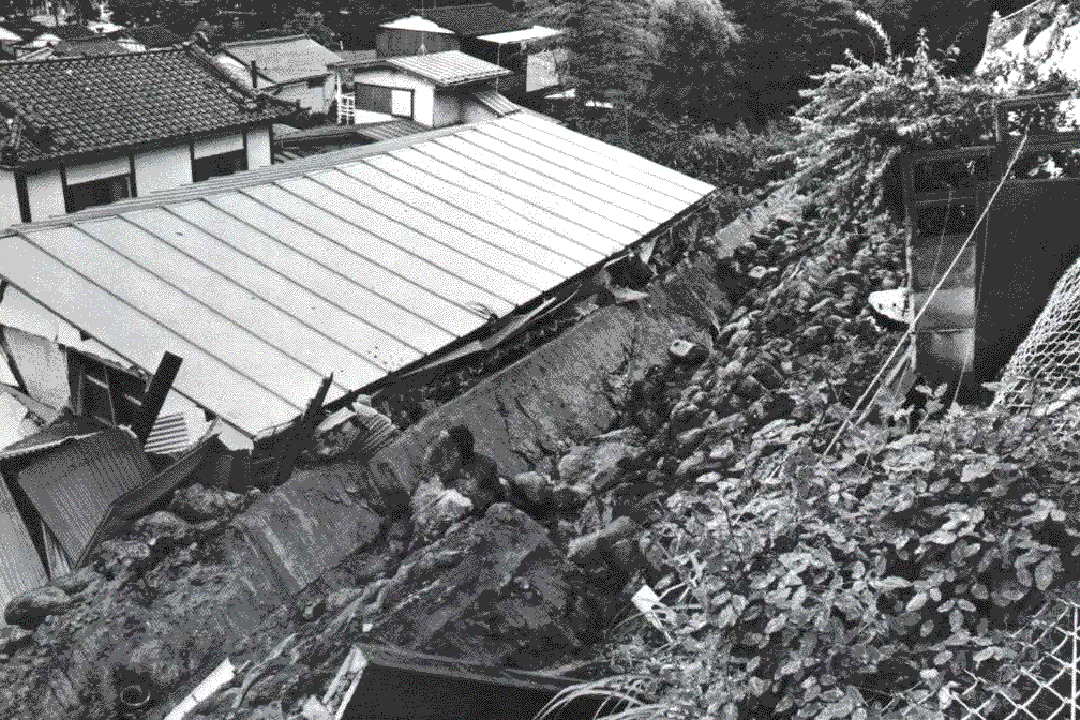

*Photo Above: Landslide caused by offshore earthquake in Miyagi prefecture (1978)

- Masaki Urano

- Professor, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences

- Born in Tokyo in 1950, Professor Masaki Urano graduated from Waseda University Faculty of Political Science and Economics in 1973 and completed his studies at the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences in 1981. He has taken posts such as a researcher at the Institute for Future Technology, and an assistant, full-time lecturer, and associate professor at Waseda’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences. Professor Urano is now a professor at the Faculty of Letters, Arts, and Sciences, and he also serves as chairman of the Japan Society for Urbanology and Japan Consortium for Sociological Sciences; director of the Japan Sociological Society; and a representative of the Great Earthquake Research Network.

The reality of the disaster area as seen from a sociological perspective

Sociology deals with a wide range of topics, including families, communities, cities, the environment, information media, and culture. As the current director of the Japan Sociological Society, Professor is the driving force behind a disaster response and reconstruction research project that makes use of extensive research results in these areas.

*Right Photo: A view of the city from Otsuchicho Shiroyama (2019)

“The project aims to identify optimal regional disaster recovery solutions based on cumulative sociological survey data since the Great East Japan Earthquake, and subsequently make policy recommendations for how to prepare for anticipated large-scale disasters. Our team of researchers from both inside and outside the university has been pursuing this effort since 2019.”

The environmental conditions and consequent damage sustained by the areas hit by the Great East Japan Earthquake varied greatly. There are limits to what can be done through conventional methods to rebuild these areas while recognizing their differences in social structure.

“Over the last decade, it has become clear that the government’s top-down, one-size-fits-all reconstruction policy has led to various problems and insufficient progress in the affected areas. Many issues have come to light, such as conflict between residents over reconstruction, unexpected population and industrial declines, and a sense of helplessness felt by residents as a result of projects disregarding their respective history and culture. The sociologists studying these disasters have made it their mission to expose this reality. Now that we are expecting major disasters such as the Nankai megathrust and Tokyo near-field earthquakes, I believe that we should develop an optimal solution as soon as possible.”

Natural or social phenomenon? Disaster awareness changes regions

What specific lessons can we learn from sociological surveys? Professor Urano says that four important perspectives are needed. The first is to recognize the close interconnection between disasters and social systems.

*Right Photo: Earthquake remains of Kesennumakoyo High School

“When disaster strikes, it is the magnitude of the earthquake or tsunami itself that we tend to take notice of. However, we should actually be paying attention to the social systems that have damaging effects. When a big tsunami hits an unpopulated area, it is not a disaster. Similarly, the outbreak of COVID-19 was brought about by increasing population density due to globalization and urbanization; had this outbreak occurred in a remote island, it surely would not have become a global disaster. In other words, how damage spreads and subsequently affects us depends on the social systems in place at a regional level. Therefore, it is of primary importance to clarify these social structures and consider the recognition of, and response to, major disasters.”

The second perspective is the ability to imagine both every day and extraordinary situations. This involves considering everyday social and lifestyle issues, and replacing them with extraordinary events. We also need to think about how to respond during emergencies based on daily issues. These two imaginative faculties greatly impact how we respond in times of disaster.

“For example, imagine an area where, due to its aging society, dying alone is a common occurrence. In the event of a disaster, this area would most likely experience problems such as the isolation of the elderly and difficulty in the procurement of daily necessities. In other words, daily challenges will increase tenfold or even a hundredfold during a disaster, which would certainly overwhelm the local community. The lesson here is that disaster countermeasures and simulations that merely assume emergencies are ultimately ineffective.”

The need for a seamless response in terms of both time and space

The third perspective is not drawing a clear boundary between the everyday and the extraordinary. As a matter of policy, the “stages” from daily disaster prevention/mitigation measures to disaster occurrence/recovery are clearly delineated in today’s Japan. Professor Urano explains that we should meticulously move back and forth between each of these stages, much like constantly changing gears when driving.

*Left Photo: Great Hanshin Earthquake (video screen showing buildings in flames)

“The Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act stipulates that shelters are to be provided for six months. Most reconstruction policies also have fixed deadlines. However, the actual affected areas undergo more subtle transitional stages, and policies based on timelines are often ineffective. Although budgets and measures eventually come to an end, future reconstruction policies must be proactive and take the next stage of each region’s progress.”

The fourth perspective is that, in addition to these temporal divisions, spatial divisions must also be more flexible. What we need is a “multi-disaster” and “multi-layered care” [approach] that transcends regional boundaries.

“The positioning of evacuation districts after a nuclear accident could be problematic because people’s livelihoods and even compensation amounts could vary drastically even if they only lived a block away from each other. The policy itself, which seeks to set clear boundaries, creates division in, and acts to fracture, society.”

Professor Urano presents these perspectives to the government through the Science Council of Japan and other activities, and also shares them with the private sector at symposiums.

Frequent natural disasters have changed the entire concept of regions

Professor Urano’s research centers on regional sociology, with an emphasis on environmentally induced social change. He maintains a secondary interest in disaster response. However, research into disasters—which effectively transform the region from the ground up—has become increasingly important nowadays.

*Right Photo: Locals of Ando District in Otsuchi Town watching a video at the local archive exhibition

“I have been studying local voluntary disaster prevention organizations for quite some time now, and began full-scale disaster research on the Unzen Fugen-dake eruption and the Great Hanshin Earthquake in the 1990s. What are our best options as we enter an era wherein communities are forced to gather all their resources to respond to natural disasters? As a regional sociology researcher, this question constantly plagued me. And then in 2011, the Great East Japan earthquake happened.”

The most important thing in regional community research is the power of imagination with regards to one’s locality

Professor Urano has been the director of Waseda University’s Institute for Sustainable Community and Risk Management for the past ten years, assuming this post in 2011. The Institute is an organization where researchers from both inside and outside the university gather to examine disaster countermeasures and risks to the local community. They also consider the responsibilities universities should take on with respect to future disaster preparedness.

*Left Photo: A meeting for a field study (Mugikura-zemi at Iwate University)

“The COVID-19 pandemic forced the university to undertake major policy changes. However, I don’t think that it’s entirely bad. For example, the university and disaster area are now connected online. If researchers are able to visit the site in the event of a disaster and provide universities with a status report and discuss conversations shared with locals, this would deepen students’ understanding of the disaster area. Additionally, it is an effective means of connecting students to each other. It is very important for the country as a whole that students, who have the country’s future in their hands, are aware of what is actually going on at the affected site and refine the power of their imagination. What was previously possible only through TV can now be done using a single computer.”

The most important thing in regional community research is the power of imagination. The same goes for research.

“Needless to say, field research is an important tool for regional community researchers. However, as researchers consider problem solving techniques in their quest for solutions, sharing them with locals and colleagues in the field as they convene to discuss local issues and repeating such discussions and drawing upon local realities, one also cannot deny that there are physical restrictions. If one is unable to maximize the power of imagination during such times, the disaster countermeasures that have been drawn up will end up [being treated as] “advice from the outsiders,” and engaging locals and working hand in hand to mitigate the situation would prove impossible. There has been an increase in ways that individuals could become more familiar with their local affairs and share information online, and this will definitely lead to a broadening of the possibilities for research that contribute to society.”