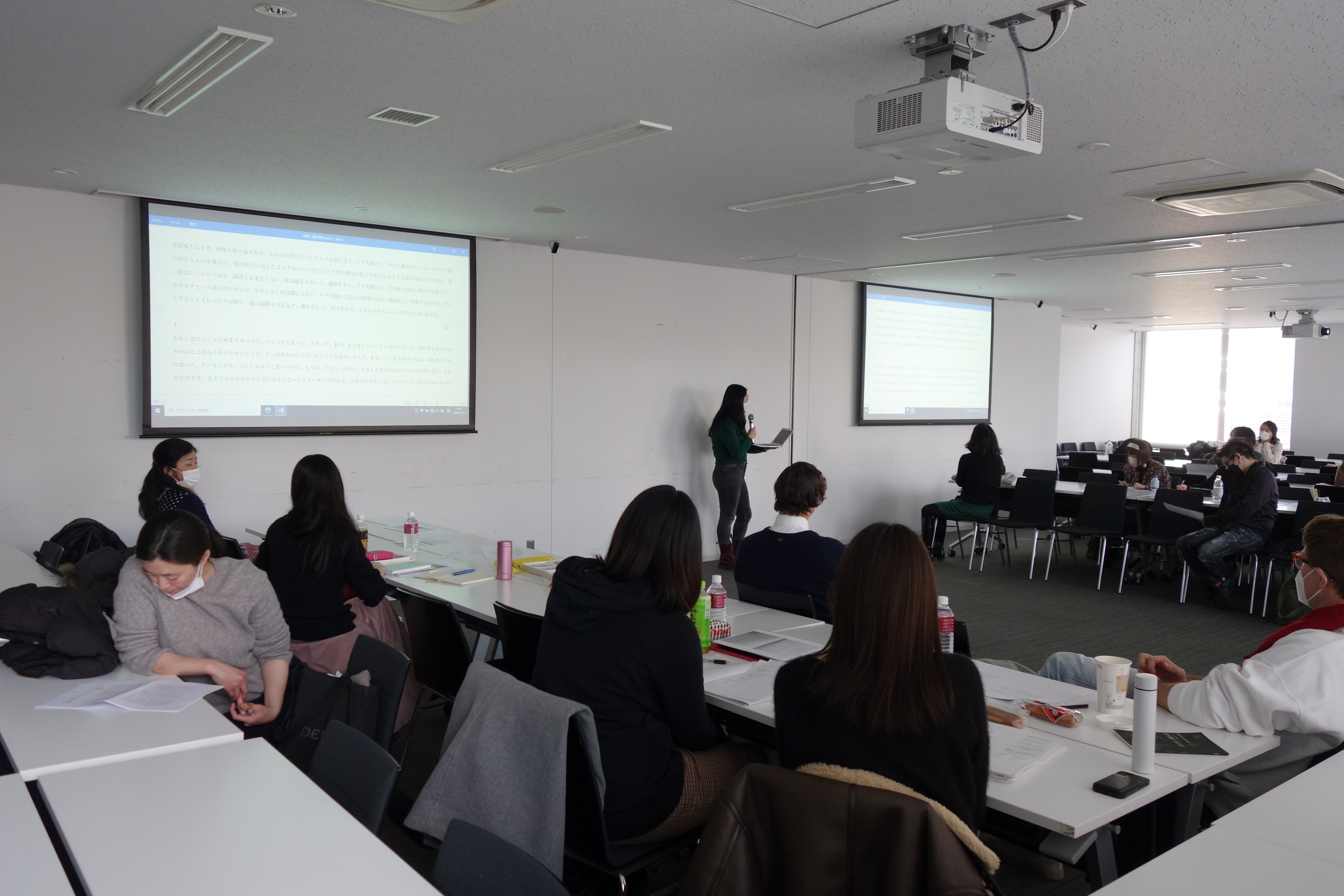

On January 13, 2022, the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences of Waseda University hosted the Translating Poetry, Translation as Poetry Workshop, a bilingual English-Japanese event in which students of the university were able to learn translation strategies and put them into practice with the help of renowned translators and poets. It was a continuation of a homonymous symposium and live-reading held by the Faculty on October 15, 2021.

The event started in the morning with an introduction by the moderators and organizers Matsunaga Miho (Professor, Waseda University) and Yoshio Hitomi (Associate Professor, Waseda University), followed by the opening remarks of the main guests: Kikuchi Rina (translator; Professor, Shiga University), Steven Karl (poet; visiting researcher, Waseda University), Jordan Smith (translator; Associate Professor, Josai International University), Hiromitsu Koiso (translator), and Itō Hiromi (poet).

The first part consisted of presentations on individual translations by students who already had experience in the field, such as Jun’ya Hirata (alumnus, Waseda University), Ryosuke Tomidokoro (MA student, Waseda University), and Laurel Taylor (visiting researcher, Washington University in St. Louis). The second part consisted of collaborative translations. For this, students were divided into four groups, two of them focused on Japanese-to-English translation, one focused on English-to-Japanese translation, and one focused on classic-to-modern translation. Each group was mentored by the main workshop leaders.

The first group was mentored by Rina Kikuchi and Steven Karl. Through the reading of passages from Misaki Takako’s Akarui mizu ni naru yōni (2020), Kikuchi explained the importance of deeply understanding the meaning of a poem and getting to its semantic roots. When diving into the translation itself, Karl explicated that translation does not necessarily use the translator’s own poetic voice, but rather his or her sensibility. Both mentors used the resulting translations of the students as an example of this. According to them, the students had interpreted the tones and emotions of the poems in very different ways, hence obtaining different target texts, yet each capturing the essence of the original. Later on, such a diversity was made evident as the group did a simultaneous performance of their translations, bringing forth their differences in rhyme, tone, and word-choice.

The second group was mentored by Jordan Smith, working on one of Yūki Nagae’s poems in Fuzai toshi (2018). From the start he told the students about the importance of paying attention to what he described as the “easy things” within a poem. These are, according to him, those that seem easy to understand and translate, yet hold more meaning than a first look might suggest. He claimed that a good portion of translation studies focuses on the ways in which complex texts seek to innovate language, poetry, and even in medium techniques, while sometimes undermining the importance of simplicity. Smith proposed that simple differences are never simple and instead are enmeshed with a system that spirals into huge importance. During the conversation with the students, he also highlighted the importance of nuance and tone. Finally, by bringing up examples of lexical differences within English, Japanese, and also Spanish, he gave concrete examples of how imagery changes in the target language.

The third group was mentored by Hiromitsu Koiso. Koiso had asked students to prepare in advance translations of Anne Carson’s “Short Talk on the Withness of the Body”, a narrative poem by the Canadian author. During the workshop, he conducted two exercises. The first exercise was to have students re-translate their own translation, but this time making it target a children’s audience. This helped him explain how translators have to adjust the writing style of a given source at their own discretion when the target audience changes. The exercise also brought up a debate about changing or deleting words in the original, specifically those that would be difficult to understand for children. As a second exercise, Koiso made the students re-translate their translations into a 5-7 metric system known in Japanese literary studies as shichigochō. By setting restrictions on the sound and rhythm, Koiso showed the students yet again the need to add, change or delete words in any translation.

The fourth group was mentored by Hiromi Itō. Itō had brought Ōgai Mori’s story “Maihime” (Dancing Girl) separated into paragraphs in advance and distributed the parts to the students. She instructed them to use an online machine translation service to translate the fragment into another language, then asked them to re-translate it back into Japanese, a process which greatly altered the text and made students debate about the need to “reconstruct” a source text. The students used other services to further expand the limits of translation: among others practices, they inputted the source text into the online machine translation service through recitation or used an AI service that alters text into a visual form based on ukiyo-e pieces. Finally, the group was also instructed to rewrite the source text by changing its point of view from Toyotarō’s (the male protagonist) to Elise’s (the German character that gives title to the story). These activities sought, according to Itō, to show students the variability of translation and help them envision the creative aspect of it.

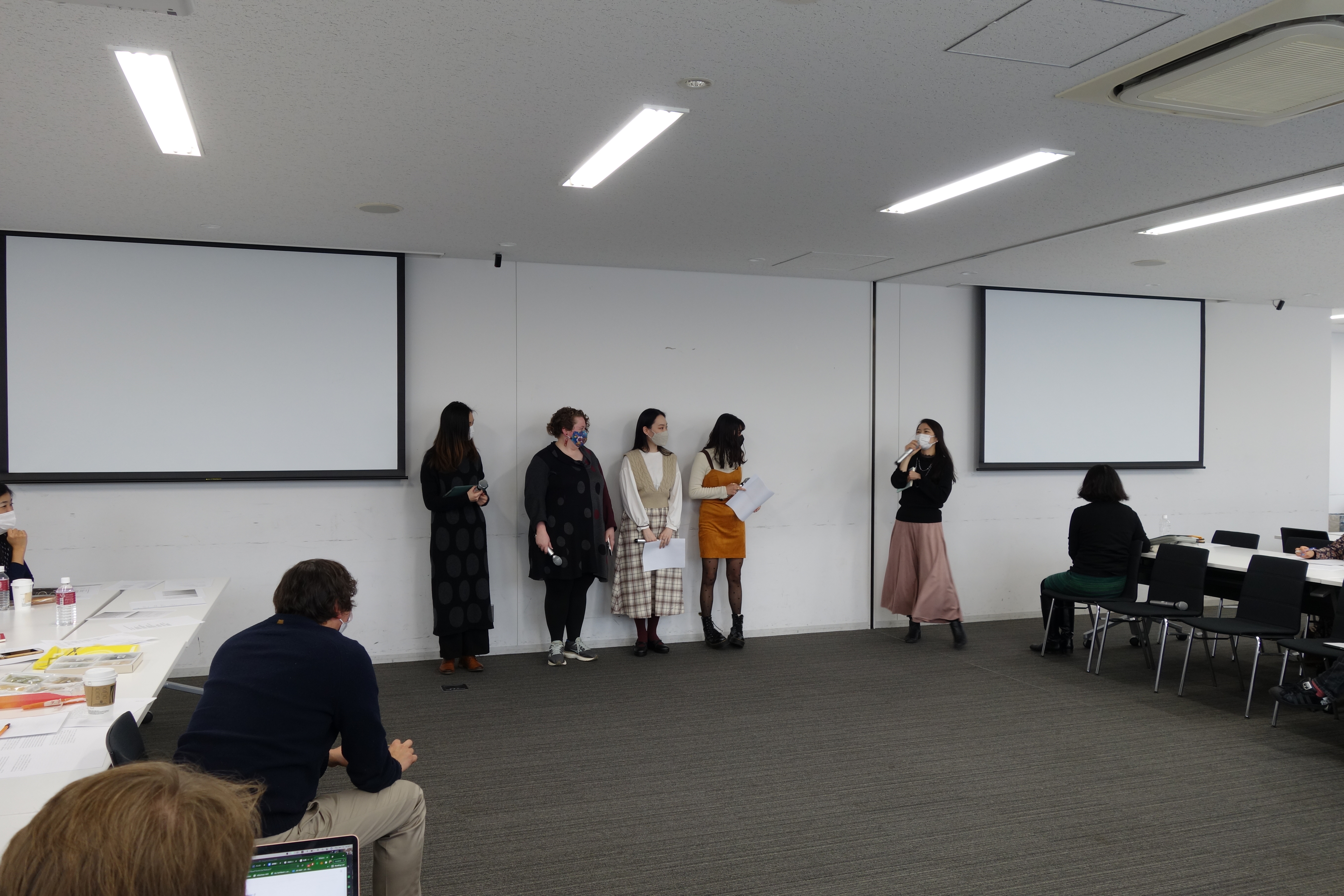

In the afternoon, each group presented the results of the work they had done during the morning through a performance. This final presentation of all of the participants served, in tandem, to bring forth questions about the importance of keeping in mind performance and recitation when translating and composing poetry. The closing remarks of the main guests and organizers concurred that the workshop had helped students to learn the ropes of translation and to explore the potential of poetry and creative writing.