“The only thing humans can put effort into is what they find interesting.”

Chief Priest of Otokonushi Shrine / Professor, School of Human Sciences, Kanazawa Seiryo University

Shigenori Omori

At Okuma Garden on Waseda Campus

Nanao, Ishikawa Prefecture, is located in the center of the Noto Peninsula. There is a man who is the chief priest of Otokonushi Shrine, which boasts a history of over 1,300 years, a university Professor, and an Olympian who livened up the Japanese athletics world in his younger days. His name is Shigenori Omori, 65, and he graduated from the School of Education at Waseda University. He is known as the "fastest priest in the world." We spoke to him about his turbulent life, from his childhood worrying about taking over the family business, to his student days striving for the Olympics, to now working hard to support the reconstruction of his home prefecture of Ishikawa.

After much deliberation, I discovered the commonalities between "festivals" and "sports"

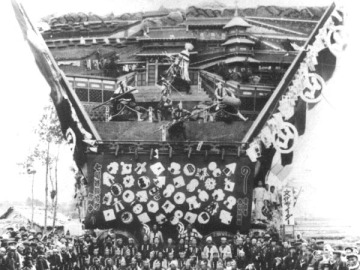

Every May, the largest festival in the Noto region, the Seihaku Festival, is celebrated with great excitement as the “Dekayama” float, which stands 12 meters tall and weighs 20 tons, is pulled around the city, and is said to be the largest float in Japan. Omori spent his impressionable childhood as a child of the Daichishu Shrine, the stage for this festival, which has been designated an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO.

Left photo: Otokonushi Shrine. Founded in the early Nara period, the current shrine building was built in 1913 (Taisho 2). Locals affectionately call it "Sanno Shrine" or "Sanno-san," a reference to the place name.

Right photo: A documentary photo of the "Dekayama" from 1923 (Taisho 12). The Seihaku Festival is said to have begun in 981 (Tengen 4), but records show that the float took on this shape and size in the late Muromachi period.

"The entire town is involved in the festival, and school was always full of talk about it before and after the event. Ever since I was old enough to understand, I felt the pressure of knowing that one day I would have to take over. If my future was already decided, I wanted to focus on something I could complete while I was still young! That's how I started track and field."

Omori started running in junior high school and reached the top level in Japan in the 400m hurdles during his high school years. His family wanted him to go to Kokugakuin University where he could study Shinto, but he overcame their wishes and chose Waseda University instead.

"At the time, I was half-hearted about not wanting to take over the business, and half-hearted about the fact that I probably had to. So my father gave me the condition that I wouldn't have to take over the business: either get accepted into the University of Tokyo or compete in the Olympics. So I decided that my goal was to become an expert in track and field, and I chose Waseda, a strong team."

During his time as a member of the Waseda University track and field team, he was ranked in the world and competing in the Olympics became a realistic goal. However, the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics were held the year after he graduated from university. With an eye on his future, Omori decided to graduate from Waseda University and enter Kokugakuin University.

"When my chances of competing in the Los Angeles Olympics loomed, I told my father about my old promise, but he dismissed it, saying, 'I said, if only I could go to the University of Tokyo and the Olympics,' (laughs). In any case, I had made a promise with my family that I would enter Kokugakuin after graduation. Although I had heard from a member of the Japan Association of Athletics Federations about me going to America to study athletics, a lack of confidence was also a reason why I couldn't take the plunge. However, I was nervous before the Olympics. There was no environment where I could practice at Kokugakuin, and at times I felt like I had no one on my side."

Looking for a better training environment, Omori decided to aim for the Los Angeles Olympics as an athlete for the Waseda Athletic Club, which is made up of alumni from the Waseda University track and field club. What motivated him was the sight of his juniors on the track and field club working hard together.

"None of the athletes had any track record, but they made up for that by practicing extremely hard. The relay at the time was even talked about as a new Japanese student record set by an unknown quartet. I enjoyed the days I spent practicing intently with these juniors."

Omori then competed in the Los Angeles Olympics. After that, he continued his studies at the graduate school of Nippon Sport Science University after obtaining a Shinto priest qualification at Kokugakuin University, aiming to compete on the world stage in athletics. The study of anthropology and festivals there proved to be of great significance to his later life.

"I had been running as hard as I could, but I sometimes wondered, 'Am I doing this because I like it? Or is it to escape from religious ceremonies and festivals?' But then I realized, wait a minute. The people involved are pulling the largest float in Japan, so the physical strain they put into those festivals is no joke. And everyone is putting their life on the line in this. It's just like sports! I realized. I wanted to think about this issue in depth, so I pursued my research as a researcher."

A photo of Omori (center) competing in the 400m hurdles at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. He placed 5th in the qualifying round.

How to make difficult things fun

Omori retired from professional athletics due to injury and returned to his hometown at the age of 29. There he spent busy days rooted in his hometown as a Shinto priest, teaching, and coaching the Japanese national track and field team.

"The people of Noto were delighted to see the return of the priest who had participated in the Olympics! Although I caused a lot of trouble due to my various duties overlapping, the days spent chatting with the local people over drinks also served as fieldwork for me to think about the festival."

In this day and age where common sense, including compliance, is constantly being updated, what is required of festivals that have been passed down since ancient times?

"Festivals have become cultural assets, and there is a demand for them to be promoted as tourist attractions. However, while festivals that have become cultural assets are beautiful, they can also lack excitement. In order for festivals to survive in rural areas with declining birth rates, the first step in revitalizing the region should be to not get too hung up on preserving tradition, but to come up with new ideas, even if only a little at a time, each year and make them enjoyable."

Left photo: Performing a Shinto ritual (Big cup ceremony) as a chief priest

Right photo: The Tokyo 2020 Olympic Torch Relay on June 1, 2021. The torch was passed on to the Japanese representative at the Los Angeles Olympics and the chief priest of Otokonushi Shrine

Meanwhile, the Noto Peninsula earthquake struck on January 1, 2024. Nanao, where Otokonushi Shrine is located, was also severely affected.

"It was New Year's Day, so there were probably several hundred people in the grounds. There have been cases of torii gates collapsing at other shrines, but our stone torii gate did not fall. If it had collapsed, there may have been fatalities. However, if you look at Noto as a whole, the situation is dire. The disaster has propelled us forward 20 to 30 years. Noto is now at the forefront of the various problems that regional Japan will face in the future."

There has been a sudden acceleration of aging, depopulation, lack of successors, and decrease in jobs. The existence of "shrines" and "festivals" that are rooted in the community can be a source of support in overcoming the overwhelming number of challenges. For this reason, Omori is placing more importance than ever on conversations with local residents.

The state of the Otokonushi Shrine building immediately after the earthquake (left), and other shrines in Nanao (right)

"I talk to a lot of different people in a lot of different places. Or rather, I listen to them. The worries are deep, but the people of Noto are patient. Through repeated conversations with everyone, we were able to revive the 'Dekayama' after a two-year hiatus in 2025, after having to hold the Seihaku Festival as a religious ceremony only in 2024. The preparations are hard and expensive, but smiles are everywhere. We still have to decide what to do about this from next year onwards, but I think we've taken the first step."

A scene from the float parade of the Seihaku Festival, held from May 3rd to 5th, 2025. On the front stage of the "Dekayama" in the foreground on the left side of the photo, you can see the words "Noto Peninsula Earthquake Recovery Memorial."

View this post on Instagram

Photos and videos of the Seihaku Festival (from Otokonushi Shrine Instagram)

Another step towards recovery is the Noto Ekiden, a three-day race in which participants travel around the Noto Peninsula in a sash. The project is to revive the legendary event, which was held a total of 10 times between 1968 and 1977 and was considered one of the three major university ekiden races at the time, alongside the Hakone Ekiden and the All-Japan University Ekiden.

"Although much has yet to be decided, we want to create something that local people can participate in to help with the recovery effort. We also want to propose a new style of university sports. There's no point in creating a competition similar to the Hakone Ekiden, so we're asking students for their opinions and considering various directions."

Even in the face of great difficulties, Omori remains future-oriented and keeps moving forward. He also gives advice to students looking to the future: "How can you make difficult things interesting? If you can do that, it will be fun."

"The only thing humans can put effort into is something they find interesting. In my case, that was the 400m hurdles. I always felt like throwing up after practice, but if I worked hard my record improved, so it was fun, and I was able to do it while laughing. I hope everyone can find something that they find truly interesting and that will help them overcome anything. At my age, I realize that life is short. There are so many things that I have wanted to do but have not been able to. Try to challenge yourself to the fullest while you are young and enjoy difficult challenges."

Interview and text: Naoto Oguma (2002 graduate of School of Letters, Arts and Sciences II)

Photo: Seiji Ishigaki

【Profile】

Born in Nanao, Ishikawa Prefecture in 1960. Graduated from the School of Education at Waseda University, the Department of Shinto Studies at the Faculty of School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Kokugakuin University, a master's course at Nippon Sport Science University Graduate School, and a doctoral course at the Graduate School of Sport Sciences at Waseda University. PhD (Sports Science). Participated in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics (400m hurdles, 4x400m relay). Served as coach of the Japanese track and field team at the 2000 Sydney Olympics and the 2004 Athens Olympics. Currently a Professor in the School of Human Sciences at Kanazawa Seiryo University and chairman of the Hokushinetsu Student Track and Field Federation, while also serving as the "world's fastest Shinto priest" and chief priest of Otokonushi Shrine. His research themes include physical exercise culture, festivals, and Furyu (elegant style) (※).

*This refers to dancing accompanied by musical accompaniment and a procession of gorgeous floats.

Otokonushi Shrine Instagram: @sannouotokonushijinja

![[Save version] Map of the four main campuses](https://www.waseda.jp/inst/weekly/assets/uploads/2025/09/17cb2975123fc5103172ef60bd98608d-610x458.jpg)