Watching movies, reading, writing, and engaging with the media critically are forms of everyday resistance.

Joanna Marie Ligon, 2nd year master's student, Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies

In front of the monument commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Waseda-Keio game near Central Library Waseda Campus

“I am here because they were there” is what I now find myself saying whenever people ask about my research interests, career path, or why I am in a particular time and place—why I am anywhere but the Philippines, despite claiming to love it so deeply: its literature, its culture, and its people. This retort and way of thinking is something I picked up from Cultural Studies pioneer Stuart Hall, who, in one of his speeches, responded to a heckler claiming migrants had arrived without the consent of the British working class: “We are here because you were there.” The end of wars and colonization did not mark the end of colonial influence—it returned in the form of migration.

In many ways, the perspective I got from Hall mirrors my own journey. Education has opened doors for me as a woman and a minority from a third-world country, where the culture of imperialism, impunity, and colonial mentality remains deeply entrenched and reinforced by enduring colonial structures. This reality is one of my strongest motivations for applying to Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies (GSICCS) , where I am currently pursuing research in film and media—powerful platforms that shape public perception, construct social realities, and reflect or resist dominant ideologies.

I grew up obsessively consuming various forms of media and will continue engaging with them, both as a reflection of my identity and as a form of resistance. That’s why I want my path as a scholar to focus on postcolonialism and decolonization, beginning with my master’s thesis, which explores antiwar films from the United States, Japan, and the Philippines set during the Pacific War.

I pay special attention to how these films use “spectacles”*—a cinematic technique I define in my paper as moments of excess involving intense visuals and sound, such as dramatic lighting, slow motion, rapid editing, and powerful music or explosions.

(*)This is how I have defined and used the term in my paper, drawing on a combination of concepts and definitions from both Simon Lewis and Geoff King.

I gave a presentation entitled "What is Spectacle?"

These spectacles are often overwhelming and designed to make the audience pause and take it all in. You know it when you see it—or when you fall into its trap: think of Keanu Reeves dodging bullets in the Wachowskis’ “The Matrix” (1999), the Battle of Helm’s Deep in Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings”: “The Two Towers” (2002), or just about any spectacular superhero fight in a Marvel movie. In antiwar films, these spectacles typically take the form of battle sequences, massive explosions, and chaotic combat scenes used primarily for their aesthetic impact.

The antiwar films I will discuss in my thesis span a range of national and cinematic perspectives:

- Clint Eastwood’s “Letters from Iwo Jima” (2006)

- Steven Spielberg’s “Empire of the Sun” (1987)

- Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line” (1998)

- Mario O’Hara’s Filipino classic “Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos” (Three Godless Years, 1976)

- Also included is the controversial U.S.-Japanese co-production “Tora! Tora! Tora! ”(1970), whose American sequences were directed by Richard Fleischer, and Japanese segments by Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku—alongside the uncredited contribution of Akira Kurosawa, one of Japan’s most legendary filmmakers, whose removal from the project stemmed from financial and creative tensions, among others.

These works offer a lens to examine the “us vs. them” dichotomy in narratives surrounding the Pacific War—a conflict that, as John W. Dower argues in his book War Without Mercy: “Race and Power in the Pacific War” (1986), was also a racial war. In his study of wartime propaganda, Dower observed that Americans portrayed the Japanese as subhuman, hive-minded threats, often using ape-like caricatures to emphasize racial inferiority, while the Japanese depicted Americans as morally bankrupt imperialists driven by greed.

This racialized dichotomy framed the war as a clash between a pure, self-sacrificing Japan and a corrupt, materialistic West. Dower also draws parallels to earlier U.S. imperial campaigns, such as the Philippine-American War, where Filipinos were portrayed as savages and “half devil, half child”—a rhetoric used to justify colonial violence, made famous by Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem “The White Man’s Burden”. During World War II, Japanese views of Filipinos were similarly ambivalent: while considered more refined than other Asians, they were still seen as culturally compromised due to their Westernization.

In contrast to the polarized and dehumanizing narratives found in wartime propaganda, the antiwar films in my thesis attempt to present complex relationships and human emotions to suggest that the global society is moving toward peaceful coexistence and equality, and that there is more to the racial war than simply people hating one another. This may be a gesture of goodwill, but it also reveals how postcolonial dominance and persistent stereotypes continue to surface, particularly through spectacular scenes where visual grandeur shapes perceptions of heroes, enemies, victims, and historical events.

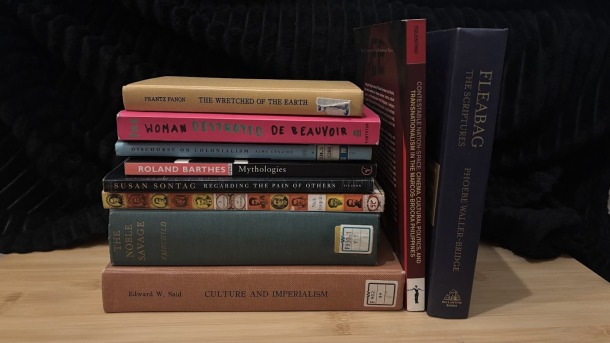

Thesis references and hobby books

My thesis, then, argues that these films’ efforts to humanize perceived enemies, especially through emotionally striking spectacles that leave a mark on audiences, produce a dual effect: they appear to deconstruct stereotypes on the surface, yet simultaneously reinforce a sense of moral or national superiority beneath it. While such portrayals may seem empathetic, especially toward Asian nations frequently subjected to racism, they elicit a more complex audience response. Emotional investment may align with the protagonist’s side, reducing the “enemy” to a symbol or narrative device rather than encouraging genuine engagement with their humanity.

Beyond the screen, the cinematic spectacles constructed by these films can serve as tools to pacify and distract the masses, thereby preserving the status quo—an idea that echoes Marxist philosopher Guy Debord’s notion of the spectacle. Such portrayals in media reshape relationships to give the impression that societies are moving toward coexistence, while underlying power dynamics remain intact, cloaked in narratives of peace and mutual respect. These very ideals, so often projected on screen, can feel more like scripted performances than lived realities, especially when the camera stops rolling and the systems remain unchanged.

While, on paper, the films I study are saturated with spectacle, the process of writing about them is far from spectacular—unless, of course, Guy Debord was right, and my thesis ambition is just another performance within the spectacle. There are countless sleepless nights, bouts of writer’s block, and the ever-present companion of impostor syndrome—a shared rite of passage for every post-grad student.

About 60% of my daily life is spent on my thesis and doing what I love: reading, writing, and watching films. The rest goes to what I merely tolerate: reluctantly participating in capitalism. A flawless work-life balance, really.

As part of that balance, and outside of being an aspiring scholar, I work as a media producer at a travel-focused creative studio in Tokyo. I also occasionally write for the Waseda University website and social media platforms through the Office of Information and Public Relations. Most recently, I covered an exclusive forum at Waseda featuring 1993 Nobel Laureate in Medicine, Dr. Richard Roberts. His talk coincided with the Nobel Prize Dialogue Tokyo 2025, Japan’s domestic counterpart to the Nobel Week Dialogue, and served as a dynamic forum for nearly 200 Waseda students, faculty, and staff in attendance.

Articles written for the Office of Information and Public Relations

There are moments in my academic and corporate life that ground me, just as there are days I find myself back in the thick of things—overstimulated by media. Writing, along with reading, watching films, and engaging with media through a critical lens, is a form of everyday resistance—my own small, intentional way of pushing back against passivity and complacency. I don’t always get it right, as capitalism, colonialism, consumerism, classism—all the oppressive Cs—and the quiet, deadly hums of homesickness are strong, constant forces, and resisting them is a daily effort. I try to make that resistance part of my daily routine, no matter how small or quiet it may seem.

Weekday routine when I am in peak productivity mode (otherwise, resistance is improvised)

Homemade champorado (chocolate porridge eaten as breakfast or snack in the Philippines)

- 9:00-10:00 Snooze my alarm about 15 times before finally waking up (I’m not a morning person)

- 11:00-16:30 Work in the library, at a café, or at the company office—mostly writing, editing, and covering PR events, with meals and mental-health walks (usually while listening to an audiobook) in between. These walks are very important for keeping me sane—and, in case anyone cares, I’m currently listening to Sunrise on the Reaping: A Hunger Games Novel by Suzanne Collins at the time of writing

- 17:00-18:40 Writing seminar with MA and PhD students (every Tuesday)

- 19:00-20:00 Dinner, either enjoying a home-cooked meal alone or dining out with friends at a restaurant in Waseda, Takadanobaba, or Ikebukuro

- 21:00 Watch a film or an episode of whatever series I'm currently into (Apple TV+'s Severance at the time of writing)

- 22:00-24:00 Read a book or work on my thesis

- 24:00-25:00 Bedtime (finally!). Even sleep should feel a little rebellious—because rest is radical

【References】

Dower, John.War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War.New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

Debord, Guy, and Ken Knabb. The Society of the Spectacle. London: Rebel Press, 2005.

Hall, Stuart. “General Introduction: A Life in Essays.” In Essential Essays, Volume 1: Foundations of Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley, 1–19. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

King, Geoff. Spectacular Narratives: Hollywood in the Age of the Blockbuster. London: IB Tauris, 2000.

Lewis, Simon. “What Is Spectacle?” Journal of Popular Film and Television 42, no. 2 (2014): 105–12.

![[Save version] Map of the four main campuses](https://www.waseda.jp/inst/weekly/assets/uploads/2025/09/17cb2975123fc5103172ef60bd98608d-610x458.jpg)