Professor Hirokazu Toeda, scholar of modern Japanese literature

School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Part 3: Ginza during the occupation – The dual nature of literary censorship

In Part 3, Professor Hirokazu Toeda at the School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Professor Robert Campbell at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences discuss the town of Ginza from the reconstruction period after the Great Kanto Earthquake up to the post-war occupation period, focusing on the key term, duality.

In Part 3, Professor Hirokazu Toeda at the School of Culture, Media and Society, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Professor Robert Campbell at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences discuss the town of Ginza from the reconstruction period after the Great Kanto Earthquake up to the post-war occupation period, focusing on the key term, duality.

(Date: April 25, 2016)

Campbell: I started using oral history methods when I began to investigate Ginza as part of my research. There tends to be major emphasis on material evidence in early modern literature, and so up until then, I had only carried out bibliographic research. However, Ginza is a town that began to flourish in recent times. Because there are many people still alive today who remember those days, I felt there is no way I would not talk to them directly. Through this experience, I observed two sides of Ginza during the occupation.

Firstly, there was a duality among the Japanese residents. The Kobiki-chō vicinity in Ginza was known as a red-light district while from Ginza Yon-chōme to Nana-chōme was a shopping area. From my interviews, I felt a sense of conflict and territorial inviolability among the people living in these two districts though they were both part of Ginza.

Another duality was the fluid demarcation line between the children of American soldiers and the Japanese (and their children). The only slight overlap where there was any common recognition was near the Post Exchange (or PX, US military term for a store selling food, beverages, and various other everyday goods to the military) in the Hattori Tokeiten store at the Owari-chō intersection (now Ginza Yon-chōme crossing) and the Matsuya Department Store up the road. Both were requisitioned during the occupation by GHQ/SCAP (General Headquarters, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers) and turned into PXs. Although there was an abundance of food at this store for the US military and their families, Japanese children had no chance of tasting but only smelling it, leaving behind bitter memories.

In addition, the Imperial Hotel and Takarazuka Theater, west of Sukiyabashi, were also requisitioned. Because Japanese children never entered them, they remain virtually blank areas in their mental maps.

Although this demarcation line did exist on any map, former pupils of Taimei Elementary School can also remember singing Happy Birthday in their katakana English to celebrate the 70th birthday of General MacArthur. Perhaps we could say that such renditions of Happy Birthday can also be considered part of the Ginza soundscape.

What do you think of the dual nature and duality of the control of speech manifest itself in literary works of that time?

Toeda: Although the way of regulating speech was different under US military occupation, Japan’s various media seemed quite aware of imperial Japan’s own recent censorship before and during the war. The control of speech under censorship by the Home Ministry prior and in wartime differed from that under censorship by GHQ/SCAP during the occupation years.

Between these two forms of censorship was continuity and discontinuity. Early on in the occupation, there were conspicuous cases of discontinuity when the authorities issued warnings without fully understanding that GHQ/SCAP’s control of speech stopped short of explicit censorship.

Under censorship by the Home Ministry, there had been a long, continuous period during which publishers conducted voluntary regulation by replacing seemingly restricted words with blank text such as “xxx,” “,,,,,,” or “……” in order to avoid having a book banned, but such censorship was explicit. An example of a publication containing such omitted words is Kafu Nagai’s “Tsuyu no Atosaki [During the Rainy Season]” (1931), mentioned in Part 2 of our dialogue.

Campbell: According to Nagai’s diary, he finished writing “Tsuyu no Atosaki” in May 1931. It appeared in the Chuokoron magazine that October before certain words were blanked out and the book was released in November. At the time of publication, there were quite a lot of censored parts. This is explained by Professor Kunihiko Nakajima of Waseda University in “Nagai Kafu ‘Tsuyu no Atosaki’ no Honbun to Kenetsu [The Text and Censorship of Kafu Nagai’s ‘During the rainy season’]” (Suzuki, Tomi., Hirokazu Toeda, Hikari Hori, and Kazushige Munakata, eds. Ken’etsu, Media, Bungaku: Edo Kara Sengo Made [Censorship, Media and Literary Culture in Japan: From Edo to Postwar]. Tokyo: Shin’yōsha, 2012.

Photo: Suzuki, Tomi., Hirokazu Toeda, Hikari Hori, and Kazushige Munakata, eds. Ken’etsu, Media, Bungaku: Edo Kara Sengo Made [Censorship, Media and Literary Culture in Japan: From Edo to Postwar]. Tokyo: Shin’yōsha, 2012.

This volume integrates research results from the “Censorship, Media, and Literary Culture in Japan: From Edo to Postwar” symposium held at Columbia University in 2009 and Waseda University’s “New Japanese Literature and Japanese Culture Research Through Co-creation with the World” Columbia Project. This is the Japanese and English bilingual edition based on the concept of the symposium’s planning stage. (Source: Shinyōsha)

When “Seimei no Ki [Tree of Life]” (first published in Fujin Bunko magazine in 1946) by Yasunari Kawabata, the author of “Asakusa Kurenaidan [The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa],” was censored by GHQ/SCAP, the following two sections referring to the war and the occupation were deleted: “It was a kamikaze death, a special death,” and “It was a death around which, to a radius of nearly four kilometers, ten or twenty thousand people moved. At the time, it seemed to be a death on which the destiny of the country hinged.”

Campbell: In the works of Tomoichirō Inoue, who we mentioned in Part 2, the occupying military forces do not appear at all in spite of the historical backdrop of the occupation. Is this also due to the influence of GHQ/SCAP censorship?

Toeda: I assume it played more than a small part. In addition, publications were not the only media subject to censorship by GHQ/SCAP. Mass media such as newspapers, magazines, books, broadcasts and films, and even personal communication media such as letters, telephone calls and telegrams were regulated also.

Photo: Yamamoto, Taketoshi., chief editor. Kawasaki, Kenko., Hirokazu Toeda, and Kazushige Munakata, eds. Senryōki Zasshi Shiryō Taikei [Compedium of Magazines During the Occupation]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2010.

The book is a summary on censorship of various literary genres during the occupation (Source: Iwanami Shoten)

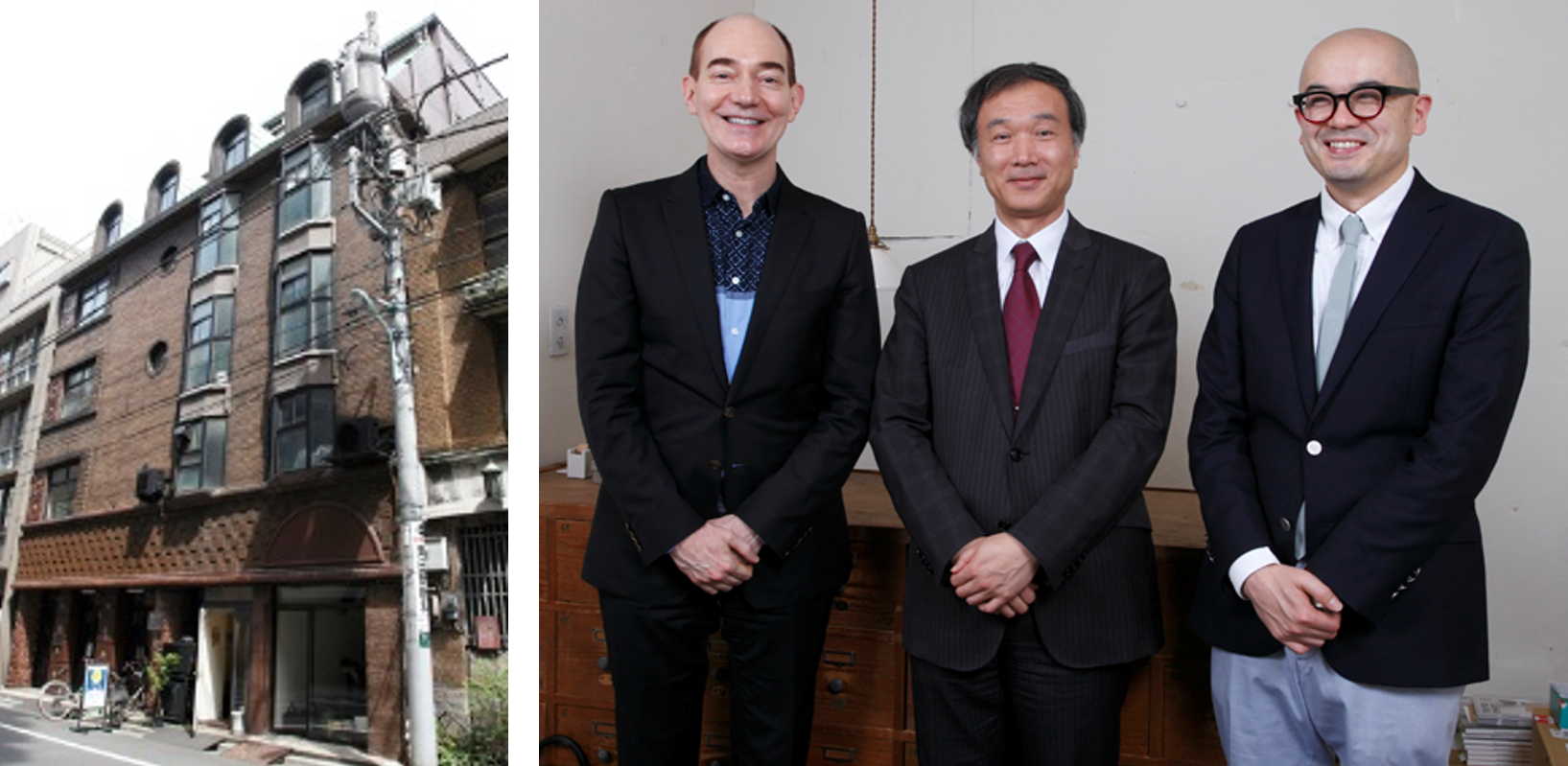

Photo: Professor Campbell and Professor Toeda holding the photo collections they each brought of Ginza during the occupation next to each other and checking photo locations, angles and dates

In the next, final part of the dialogue with Professor Campbell, he will discuss the global spread of Japanese literary research and its prospects for the future.

Profiles

Professor Robert Campbell

Professor Robert Campbell

Born in New York, Professor Robert Campbell graduated from University of California, Berkeley and earned a PhD in literature from the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University. He moved to Japan in 1985 as a research student in the Faculty of Humanities, Kyushu University, later joining the faculty as an assistant professor. He also served as associate professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature and associate professor and later professor at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo. His specialization is Japanese literature from the Edo to Meiji period. His publications include “Robert Campbell no Shosetsuka Shinzui—Gendai Sakka Rokunin to no Taiwa [Dialogue With Six Contemporary Artists – Novelist Essence of Robert Campbell]” (NHK Publishing, 2012), “J-Bungaku—Eigo de Deai, Nihongo wo Ajiwau Meisaku 50 [J-Literature: Fifty Masterpieces to Encounter in English and Relish in Japanese]” (University of Tokyo Press, 2010), “Kanbun Shosetsu Shu [Meiji Novels Written in Classical Chinese]” (Iwanami Shoten, 2005), “Yomu Koto no Chikara―Todai Komaba Renzoku Kōgi [The Power of Reading―Lectures at Komaba, the University of Tokyo]” (Kodansha, 2004) and “Kaigai Kenbun Shu [A Collection of Observations from Abroad]” (co-writer, Iwanami Shoten, 2009). He is also active in the Japanese media where he utilizes his expertise in literature as a television host, news commentator, newspaper columnist, book reviewer and radio personality.

Professor Hirokazu Toeda

Professor Hirokazu Toeda

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Professor Hirokazu Toeda graduated from Waseda University’s then School of Letters, Arts and Sciences before going on to study Japanese literature the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, where he obtained his PhD in literature. He served as an assistant professor at Otsuma Women’s University before returning to Waseda University as an associate professor. He has served as a professor since 2003. He also frequently takes on collaborative posts overseas, such as visiting professor at UCLA in 2015 and visiting researcher at Columbia University in 2015 and 2016. Professor Toeda received the Utsubo Kubota Prize for Literature in 1994. His field of specialization is modern Japanese literature (literary modernism centered on the New Sensationalist school of Japanese writers, modern Japanese literature and the media and the interrelation between literature and censorship during the Allied occupation, etc.) His publications include “Shigeo Iwanami—Living Low, Thinking High” (Minerva Shobo, 2013), “Masterpieces Can Be Made—Yasunari Kawabata and His Works” (NHK Publishing Inc., 2009), “Censorship, Media and Literary Culture in Japan: from Edo to Postwar” (co-author and co-editor, Shinyosha, 2012), “Survey of Magazines during Occupation—Literary Edition, Volumes 1-5” (co-author/editor, Iwanami Shoten, 2009-2010), “The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature” (co-author, Cambridge University Press, 2015), and a commentary on Parts 1 and 2 of Riichi Yokomitsu’s “Ryoshu” (Iwanami Shoten, 2016).

The venue

Morioka Shoten, Ginza Branch

The dialogue took place at Morioka Shoten, Ginza Branch, located on the first floor of Suzuki Building in Ginza-Itchōme. Under the concept of “selling one book at a time,” this store adapts the unique business style of selling only one kind of book per week and creating elaborate displays, which attract many visitors from abroad as well.

Photos, Left: Morioka Shoten Ginza Branch in Ginza-Itchōme Right: (From left) Prof. Robert Campbell, Prof. Hirokazu Toeda, and Morioka Shoten Manager Yoshiyuki Morioka