Aiming for a new social system “with children”

According to a survey published by UNICEF in 2020, the mental well-being of Japanese children is 37th out of 38 countries. It was almost the last place. Why is it that, even though Japan ranks first in physical health, cases of abuse, suicide, and emergency visits to child consultation centers are not decreasing? Let’s listen to the story of Professor Kazuhiro Kamikado, who founded a research institute to reform Japan’s social welfare system and improve the situation of all children.

◆ Society-wide care for the benefit of all children

──What does “social care” mean?

Kazuhiro Kamikado (Director/Professor, Faculty of Human Sciences)

Although the term is similar, the more commonly used term “social welfare” has been used for a long time. The Child and Families Agency explains it as “publicly responsible social protection and care for children who cannot be properly cared for by their guardians, and support for families who are having difficulty raising their children.” Reasons why children can no longer live with their guardians include abuse, poverty, and parental illness. In either case, the philosophy of social welfare is “for the best interest of the child” and “to raise children with the whole society.”

However, it would be ideal if we could provide care before they are no longer able to live with their parents. Ideally, there would be a system in place that would allow society to provide the necessary support for families and parents and children at an early stage, which could be called “prevention.” In other words, I believe that parents and society working together to raise children in order to improve the situation of all children, including preventive measures against parent-child separation, is “social foster care,” a broader version of social care.

──Does this mean that the previous approach did not provide sufficient care for the children?

Society guarantees a “place to grow up” for children who end up living away from their guardians, but this can be broadly divided into two methods. “Institutional care,” where care is provided in child welfare institutions or infant homes, and “family care,” where care is provided in a home, such as by foster parents. The global trend is toward family care, but in Japan, the overwhelming majority of children are in institutional care, with family care accounting for only 10% for a long time.

However, “attachment,” a stable bond with caregivers, is extremely important during a child’s developmental stage, and the degree of attachment is said to have a significant impact on personality development, especially in infants and young children. At least for the first few years of life, it is important for children to grow up in a safe environment and build a stable relationship of trust with a specific caregiver, such as a parent or guardian, and individual care is preferable to raising them in a group.

For these reasons, overseas, the shift to family care has progressed since the 1970s, and as of 2010, the rate of placement with foster parents was over 70% in the UK and the US, and over 90% in Australia. In Japan, family care has gradually increased as well, but currently, of the approximately 41,000 children in social care, only about 8,000 live with foster parents or other families, meaning that the rate of placement with foster parents or other families remains at around 25%.

──It seems like progress has been made from the previous 10%, but what is the current situation in Japan?

The situation in Japan has been gradually changing since the “promotion of family care” was set out in the guidelines adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2009. A major change came in 2016 with the amendment of the Child Welfare Act, which stipulated the protection of “children’s rights” and for the first time set out the principle of “priority for family care.” To achieve this, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare presented a “New Social Foster Care Vision” in 2017, and following the formulation of prefectural social foster care promotion plans in 2019, practical efforts have begun in each local government from fiscal 2020.

This promotion plan will be implemented for 10 years. In other words, whether Japan can build a “new social foster care system” and realize a system in which “parents and society work together to ensure children’s upbringing” will depend on the challenges we face over the next 10 years. Our “Research Institute for Children’s Social Care” was launched in 2020 with the mission of supporting this movement.

◆Reforming Japan’s welfare system through research, practice, and policymaking

──Professor Kamikado, you are also a child psychiatrist. How did you begin your research into foster care?

A dozen years ago, I worked as a child psychiatrist at a child consultation center. While dealing with various children, such as children with disabilities, children who did not go to school, and children who were abused, I often encountered situations where I felt that there was a limit to what medical care could do. The situation of children in social care is particularly difficult, and even if they are separated from their parents to protect them due to abuse or other reasons, their safety and security is not necessarily guaranteed. I learned that in temporary shelters and later in facilities and foster homes, children are further abused, and violence between children is ignored. One time, a child told me, “I’d rather be hit at home than be protected,” and I felt a lump in my throat.

Child consultation centers, welfare facility staff, government officials, and doctors are all working so hard, but why is it that abuse is not decreasing? Surely something is still missing. Of course, it is important to detect and intervene early if there is a problem, and to secure a safe place. But if we could help children and parents at an earlier stage before problems occur, parent-child relationships might not fall apart, and abuse might be prevented. Even so, when separation from parents is unavoidable, I hope that we can live in a society that provides a place where parents can find someone who will live with them. That’s what I thought.

To achieve this, we need welfare. If we could change the welfare system and structure, I’m sure we could save many more lives before medical treatment. So I went back to university and got a doctorate in the sociology of welfare.

──So you established the Project Research Institute to sort out these problems and find practical ways to solve them.

Yes. I came to Waseda in 2019, but there were still no universities in Japan that had established such a research institute, so I thought it was significant that Waseda was taking the lead in this effort. In countries such as the UK and the US, research on foster care has progressed, and evidence-based research findings have led to on-site practices and government policies, which have supported the transition to family care. Unfortunately, no such major movement has been seen in Japan, and there has been a lack of research and evidence to guide practices and policies in foster care.

So I thought, why not seize this opportunity when momentum is budding for the creation of a new foster care system in Japan and begin by working with children in foster care, who have been placed in the most difficult circumstances? Fortunately, I received support from professors in the School of Human Sciences and specialists across the country involved in child welfare and medical care, as well as generous support from the Nippon Foundation, which enabled me to establish the Research Institute for Children’s Social Care.

The institute’s mission is to use this as a starting point to advance “empirical evaluation and research,” provide “practical support” based on the results, and then link this to “policy recommendations” that provide suggestions for policy measures.

◆Establish a local government model and expand it nationwide

──Please tell us about your specific activities. What kind of ideas do you have in mind?

Our ultimate goal is to improve the situation of all children, but this cannot be achieved overnight. Therefore, we first focused on children in social care, and we thought that if we could achieve results in improving their situation through cooperation between the national and local governments, this would have an impact on many other children. To achieve this, we need to create an environment where children can receive support from various people in the community, such as schools and hospitals, while being cared for by foster parents.

Foster parents are not parents. They are forced to live apart, but when the parents are able to be with their children, it is desirable for the children to return to their parents if they wish. Foster parents of the future will live with the children until then, maintain contact with the parents while preparing to return, and raise the children together with the parents so that a safe and secure place for the children to grow up is maintained even after they return home, so that parents and children are not separated in the first place.

In order to increase the number of such foster parents in Japan, we need to develop training and support programs. At the same time, we need to develop human resources who can connect parents, children, foster parents, and the community, and we need to introduce the results of previous research on foster care from overseas. Based on these empirical studies, we also want to support the efforts of model local governments and lay the groundwork for horizontal expansion across the country. Furthermore, we want to start a “youth conference” to listen to the opinions of people (youth) who have grown up in social care and incorporate their perspectives into research, practice, and policy. In this way, our activities have expanded rapidly.

──That’s why you have so many projects going on at the same time. How are the results coming out?

“Training on local government model projects for promoting family childcare”

As an example, a “Municipal Model Project” is being carried out smoothly, based on the efforts of Fukuoka City, which is considered to be the most advanced in Japan, and expanding it to Oita Prefecture, Yamanashi Prefecture, and other prefectures. Fukuoka City is promoting an environment called “permanency guarantee” where there is someone who will live with the child forever, and the rate of foster care placement has already reached the same level as Europe and the United States. The methodology has been organized and adjusted so that it can be put into practice in other municipalities, and the method has actually been introduced in Yamanashi Prefecture, where results are beginning to be seen.

In addition, we have been commissioned to carry out research related to the creation of guidelines based on the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare’s “Guidelines for the Formulation of Prefectural Social Foster Care Promotion Plans,” which we mentioned earlier, so that local governments can advance specific plans based on these guidelines. The results of the research have already been compiled into a report in March 2024, and we hope that this will serve as an opportunity for the initiative to spread to many local governments.

The 25th National Conference of the Japanese Society for Child and Family Welfare (held at Ibuka Masaru Memorial Hall)

As an activity unique to Waseda, we are also working on human resource development. In addition to training staff from local governments, child consultation centers, and private support organizations, we are conducting research and training on the training of “child and family social workers,” for which the first certification exam was held in March 2025. This was made possible through collaboration with the West Japan Child Training Center Akashiya, other universities, and private organizations, and with funding from the Nippon Foundation. As a project of the Waseda University Advanced Research Institute for Human Studies, we were able to train approximately 100 candidates in the first year (2024).

Furthermore, the 25th National Conference of the Japan Society for Child and Family Welfare was held at the Waseda University International Conference Center, and for the first time, a “Presentations by High School Students and University Students” program was implemented (in June 2024). In a first for the society, eight high school students and ten university students gave presentations about their work in seminars, clubs, volunteer activities, etc. We believe that it was a great success that 120 high school and university students participated, which was more than we expected.

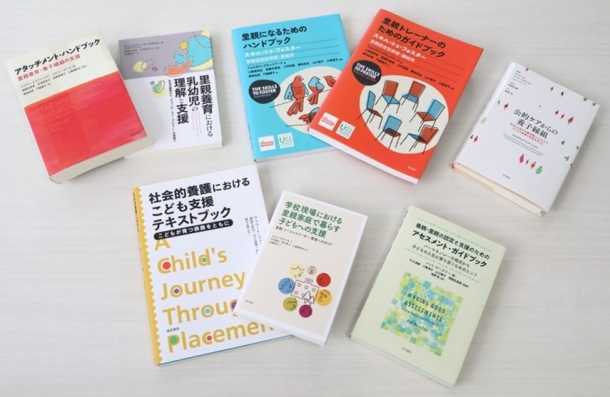

One of the results of Research Institute for Children’s Social Care ‘s activities is the publication of Japanese versions of specialized books that are needed in this field but did not exist in Japan.

◆Don’t just say “for the children,” but extend it to “with the children”

──The decision has been made to continue the institute, and a new five-year period will begin in 2025. What are your aspirations?

For the past five years, we have focused on activities related to foster care, with the main goal of improving the situation after separation of parents and children. During that time, discussions on children’s rights have become more active in the government and the Diet, leading to the launch of the Children and Families Agency in April 2023 and the enforcement of the Basic Act on Children, and we are seeing a wave of movement. Riding this trend, what we need to do in the next five years is to create a society in which parents and children do not need to be separated in the first place. We need to maintain connections with adults that are important to children, protect children’s sense of security and challenges (play), and ensure a childhood in which children can grow up as themselves.

To achieve this, we must listen to what children themselves think is safe and secure, and reflect this in systems and policies. It is also essential to involve the “youth” with experience in social welfare, and people who have worked directly with children in the welfare and education fields.

Research institute staff members Rie Nasu (left) and Misaki Arakawa. They are essential members of the team in advancing over 10 projects.

In fact, this institute has welcomed such people to its staff. Misaki Arakawa, who serves as a research assistant, is one of them. As a child who received social welfare and as an adult she has worked in child welfare institutions and infant homes, so she can evaluate research and practice from both perspectives. She is using this knowledge to help run the youth conference and launch and run a website that conveys the voices of those involved.

Another staff member, Nasu Rie, has experience working as a clinical psychologist in a school, but like me, she was frustrated that there are children who cannot be saved by education alone, so she obtained a doctorate and became a researcher. Here, as a junior researcher, she is in charge of developing training programs for school teachers and staff, and conducting research on the “Child Development Support Center Project” (Children and Families Agency) to support children who have no place at home or school. In addition, visiting researchers and research assistants in charge of each project, research staff who support the institute, as well as practitioners from local governments and private sectors who are engaged in cutting-edge initiatives across the country, and researchers in various specialized fields have joined us as visiting researchers.

──There are only five more years until the deadline for local governments to implement their social foster care promotion plans. This seems like a critical moment.

I think so. Japan’s foster care has lagged behind other developed countries, but I think that now is actually an opportunity to create a better system than other countries. Japan is now in a position to simultaneously advance both approaches: the transition from institutional care to family care, and support at the preliminary stages to prevent separation of parents and children. This is of interest to researchers in Europe and the United States, and support at the preliminary stages in particular is an issue that is still in the early stages of being addressed overseas. In that sense, the next five years will be a critical period, and I think it will be very worthwhile for Waseda University to seriously tackle this field.

We often say that we are working “for children.” However, I feel that we have not fully confirmed what kind of results our efforts are bringing to children. The Institute’s goal is not to end with “for children,” but to always think about linking it to “with children,” and to realize the present and future happiness of all children. To that end, we hope to continue to fulfill our role as a place where people from various positions gather to share ideas, engage in research that will bring about new changes, and develop practices.