A mission to use ”knowledge” to protect the heritage of humankind for future generations

The temples and streetscapes that adorn the Angkor Ruins in Cambodia, the Hellenistic villages that flourished in the west of ancient Egypt, and Chinese cities that still retain traces of the rule of Western powers… How much of the precious cultural heritage from all over the world that bears the footprints of humanity should be preserved and how should it be utilized? Research has been ongoing for the past quarter century with the aim of creating a system of “knowledge” related to investigation, restoration, preservation, and utilization.

◆ To save the world’s cultural heritage from danger and pass it on to future generations

──Since Project Research Institute system was first established at Waseda University, you have been continuing your activities for nearly a quarter of a century. What is the background to this?

KOIWA Masaki (Director/Associate Professor, Faculty of Science and Engineering)

Although the name of the institute is “UNESCO World Heritage,” the heritage sites and areas of our research are not limited to these. As of July 2024, the number of cultural, natural, and mixed heritage sites registered on the World Heritage List of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) is 1,223. In addition, UNESCO has intangible cultural heritage such as traditional performing arts and festivals, and the Memory of the World, which is a collection of valuable documents and other records. If we also include heritage sites and cultural properties designated by each country, such as Japan Heritage, the number is enormous, and is expected to continue to increase in the future.

On the other hand, the environment surrounding the preservation and utilization of heritage and cultural properties is complex and diverse, and the thinking and approaches of countries and regions are not necessarily uniform. Many things are at risk of disappearance or collapse. In such a situation, what should be preserved, to what extent, and how should they be utilized? It depends on the cultural policy and economic situation of each country, and there will also be differences depending on the degree of the crisis. With the aim of establishing a certain basic principle while taking such a balance into consideration, this institute’s activities were started about 25 years ago by now-retired Professor Emeritus Takeshi Nakagawa (architectural history), and we have continued to do so while gradually changing our activities to suit the times.

──There may be a greater need to preserve and utilize things that have not yet been registered as World Heritage sites or the like.

That’s right. It’s hard to generalize, as there are areas where the local residents have properly preserved the heritage, but in areas where the cultural value is not recognized, or where there is recognition but not enough money or effort to preserve and utilize the heritage, there is a possibility that urgent action is needed.

Many of the heritage sites in particular that are in danger are found in regions where the transmission of traditional culture was once interrupted by colonial rule or revolution, or where similar events occurred during the process of modernization. Developing countries are prime examples of this, but Japan has also experienced the loss of traditional techniques such as wooden architecture and crafts as lifestyles have evolved since the Meiji period, so developed countries are not immune to this issue either.

The institute has been conducting research, conservation, and restoration activities mainly on cultural heritage sites in the Mekong River basin, including Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar, East Asia including Japan, and the Middle East, taking into account the circumstances of each heritage site, such as climate, historical and cultural conditions, geographical relationships, and so on. In doing so, it aims to contribute to regional development and peacebuilding, and to promote diverse exchanges and cooperation between regions, as well as to advance the creation of guidelines and academic development regarding the preservation and utilization of cultural heritage sites.

◆ Preserving and utilizing historical sites, including creating disaster prevention plans, and revitalizing the city

──You also take part in the restoration of historical ruins. What kind of activities do you carry out specifically?

Excavations at Qom al-Diba, a Hellenistic site in the Egyptian Delta

We conduct practical research from multiple angles, including on-site visits, on the environments and climates in which they are located, the nature, and the policies and organizations related to cultural properties, targeting so-called ruins, urban areas, residential areas, and religious buildings. I myself specialize in architectural history and cultural property preservation, but we also have a diverse group of researchers with expertise in architectural engineering, archaeology, physical geography, geomorphological environment, environmental engineering, cultural property disaster prevention, and cultural policy, and we collaborate with other universities, research institutes, and companies both in Japan and overseas.

Regarding the restoration work on the ruins, another research group at our university’s Institute of Science and Engineering is currently working on a commissioned research project, so we are collaborating with them and complementing each other by taking on the academic research that forms the basis of the restoration work.

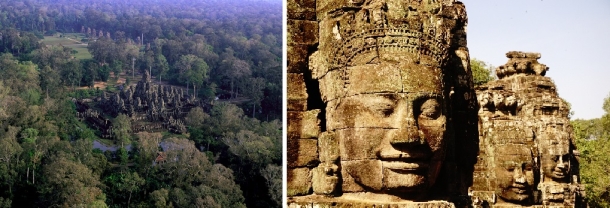

Here is a brief summary of the activities we have undertaken over the past three or four years. First, in Cambodia, we have been conducting basic research on the restoration work of the Angkor Wat, centered on the World Heritage Site Bayon Temple, which was entrusted to RIIST, as well as architectural and archaeological surveys and restoration work on the Sambor Prei Kuk ruins, also a World Heritage Site, and creating an urban preservation plan with a focus on disaster prevention in the historical district of the old city of Siem Reap, the tourist hub of the Angkor Wat. As it is necessary to balance cultural preservation and tourism development in such historical cities, we are also conducting comparative research with Amsterdam, Paris, Kyoto, and other cities.

Recently, we have expanded our scope to the Islamic cultural sphere, and participated in the Ancient Egyptian Western Delta Survey Team, which is being conducted in collaboration with the Egyptian Department of Antiquities. We visited the Qom al-Diba ruins on the shores of Lake Idq, where a village from the Hellenistic period (4th to 1st centuries BC) rests, and conducted surveying, excavation, and architectural investigations. In Saudi Arabia, we have begun research on the ruins of Howrah on the Red Sea coast, a port city that flourished in the early Islamic period (7th to 9th centuries).

Bayon Temple, a World Heritage Site that is part of the Angkor Wat in Cambodia, has been the base of operations for the research institute since its inception.

──You are also involved in preserving historical sites from a disaster prevention perspective.

Yes. There are areas where legal systems such as fire safety laws are not in place, and where firefighting activities by the government and citizens are insufficient. The old city of Siem Reap mentioned earlier is one such area. This area, known as the Old Market, is part of the Angkor ruins where the old streetscape remains, but it can also be considered a “living ruin” where people live. How can we preserve the city while protecting their lives? Fire prevention is an essential consideration.

Of course, Cambodia has fire departments and firefighters, but the number is less than one per 10,000 people even in urban areas, far from the situation in Japan, where there is one per 800 people. Moreover, I hear that the number of fires has increased by 20% every year in recent years. The Fire Service Act has not been fully implemented, and detailed measures such as the installation of sprinklers and the setting of evacuation routes have not been implemented.

Citizen-participation water discharge training using fire pumps donated by Japan (Siem Reap)

Therefore, while we appealed to the government, we decided to start awareness-raising activities to raise disaster prevention awareness among residents and provide equipment and technology for actual firefighting activities. Specifically, we held workshops on fire prevention and early firefighting, created a system in which civilians would cooperate in extinguishing fires when a fire broke out, provided fire pump trucks for that purpose, and provided training and technical guidance on how to use them.

We received cooperation from the Japan Fire Pump Association in providing equipment and training, and in terms of human resource development, we were able to organize training in Japan organized by JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency).We believe that we have achieved certain results from our activities over the four years since 2019.

◆Connecting technology and developing people: the passion behind inheriting cultural heritage

──What knowledge have you gained through activities such as research, preservation and restoration?

Many of the ruins are made of piled-up stones and bricks, which is called masonry construction, and there are some areas where Japan’s technology and knowledge, which has been cultivated mainly in the restoration of wooden buildings, cannot reach. How do these ruins collapse, and what are effective methods to prevent this? We must research using an approach that is different from that of both wooden and concrete architecture, and devise a method that is suitable for each ruin.

Therefore, rather than simply transferring Japanese technology to the local area, we need to understand the local circumstances, research appropriate technology on a case-by-case basis, and think about how to utilize Japanese knowledge. This will lead to the development of Japanese technology, and can be applied to the restoration of stone buildings in Japan. In that sense, even though we are dealing with old structures, there is the difficulty and excitement of constantly pursuing new technology.

──And it also has the benefit of contributing to local development and safety.

In practical terms, there is a possibility that tourism and other industries will be promoted, attracting people, creating jobs, and returning profits to the local area. However, that does not mean that developed countries should take a top-down approach, as if they are giving something to developing countries. Continuity is important. It is not enough to just hand over technology and carry out construction, but it is important to create a system that allows local people to preserve and utilize cultural heritage themselves after that. That is why we are working to get a wide range of local researchers, engineers, government officials, and others to participate in our projects.

What we must not forget is the development of local human resources. In order to continue protecting the ruins, it is necessary to develop the human resources who will carry them forward. As one of the initial efforts, we have opened a training center at the museum at the Sambor Prei Kuk ruins in Cambodia and are running a summer school for local university students. These ruins are also extremely important academic assets in elucidating the full picture of the Angkor ruins, and with expectations for their preservation, restoration, and utilization increasing since they were registered as a World Heritage Site in 2017, there is an urgent need to develop experts who will support these activities in the future.

When I think back, I was in my 20s and was involved in a restoration project at the Angkor Wat, and local researchers of my generation with whom I conducted research and studied are now in responsible positions in the Cambodian government, involved in the preservation of cultural heritage. From such person-to-person interactions, the seeds of research that will lead to the next generation are nurtured. That is also the role of our research activities.

──The institute’s term will come to an end in 2025. What are your plans?

I would like to begin to somehow compile the research content and results of the past few years and make them available to society or to give back to the fields of research and education. It may become something like a guideline for the preservation and utilization of historical sites.

At the same time, I also intend to broaden the scope of my activities a little and further my research that I am about to begin in China. Potential locations for my research will be Dalian, where many buildings from the Japanese colonial period remain, and Qingdao, where a Western-style streetscape was created under German rule.

Ideally, it would be better if there were no laws, policies, or research to protect historical sites. Although this is an extreme example, even if such things do not exist as a society, local people can reach a consensus and pass on valuable cultural heritage to the next generation. If such a situation could be realized in various places, I think that would be the ideal form.