Giving equal importance to all languages

“In addition to Ainu languages in Japan, many minority languages around the world are facing the threat of extinction. The model to preserving and restoring these languages may well lie in Australia’s efforts in giving minority languages equal recognition and importance as those received by major languages,” says Professor Maeda.

Professor Koiji Maeda from the Faculty of Education and Integrated Arts and Sciences at Waseda University

Professor Maeda has held positions such as the chairman of the Japan International Education Society and Japan Association for the Study of Learning Society etc. Additionally, he also has affiliation to Monash University. His recent works include a co-written book titled Nonformal Education and Civil Society in Japan (2015).

International framework for preserving and restoring languages and cultures

Accordingly to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), there were a total of 6,000 languages around the world in 2009. Among them, 2,456 were classified as endangered languages which were mostly indigenous languages without a writing system. In Japan, the Ainu language is listed as critically endangered which is the most severe level of the five levels of language endangerment defined by UNESCO. Hachijo and Ryukyuan languages on the other hand, are classified as vulnerable languages.

In September 2007, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Even though it is not bound by law, it serves as a suggestive international framework to preserve or restore languages and cultures that face the threat of extinction. Article 14 Paragraph 1 that states “indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning,” and Paragraph 2 that states “Indigenous individuals, particularly children, have the right to all levels and forms of education of the State without discrimination,” are particularly worth mentioning. The latter, especially, is a paragraph that assumes more than 5,000 Ainu diaspora currently living in the Tokyo Metropolitan, and hints the need of a framework that serves to restore the rights of the Ainu and Ryukyuan in preserving and recovering their languages and cultures.

Restoring the Ainu language that faces the threat of extinction

Although the umbrella term Ainu language used to include Sakhalin Ainu and Kuril Ainu dialects, the native speakers of Hokkaido dialect are currently the only group of people that is identifiable. Accordingly to a survey report of the current living conditions of the Hokkaido Ainu in 1999, the percentages of people age 60 or above and age between 50-59 who can still speak the Ainu language stand at 3.2% and 1.2% respectively. Unfortunately, native speakers of Ainu language outside these age groups are not identifiable. These explain why the Ainu language is classified as a critically endangered language. Behind this background lies the history of standardizing Japanese language in an effort to unite and strengthen the country, which includes having students who were caught speaking Ryukuan language wear a dialect for public humiliation. In the past, students who regularly wore the card would even face corporal punishment.

Since the enactment of the Act on the Promotion of Ainu Culture, and Dissemination and Enlightenment of Knowledge about Ainu Tradition, etc in 1997, there were efforts to restore and perpetuate Ainu language and culture. However, promotion of Ainu language and culture were seen merely as part of social education and life-long learning, and were not integrated as part of the school curriculum. With the exception of a few public schools, most schools have no intention to include Ainu language as part of the school subject.

600 over languages across all Australian Aboriginal communities

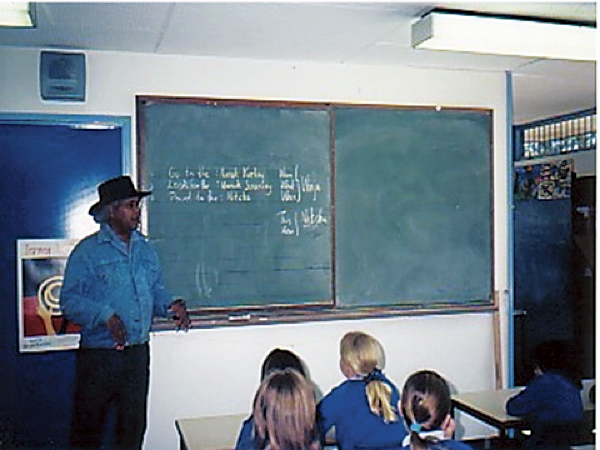

Public primary school in the Eastern State of Australia. Schools started incorporating Aboriginal language classes as part of the school curriculum about 20 years ago.

The Australian Aboriginal languages that the indigenous Aboriginal Australians speak consist of up to 27 language families and isolates. As these native Australians came in contact with the English language, they started speaking English-based pidgin languages which eventually turned into creole languages.

It is estimated that in Australia, there were a total number of 600 native and creole languages altogether. However, due to various government policies between 1910 and 1970, many indigenous Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families. This generation of children became known as the Stolen Generations. These policies resulted in a decrease of an approximately 150 languages in which roughly 100 of them face the threat of extinction.

All languages should be treated with equal importance

In the midst of all these unfortunate policies in the past, Languages Other Than English (LOTE) policy has been adopted in 1992. Under the policy, public schools in the Eastern State of Australia, where most Aboriginal Australian live, began including Aboriginal languages and English based creole languages into the school curriculum. These initiatives underlie the recognition of Australian English, as well as the native Aboriginal languages and English-based creole languages as languages of equal importance.

Additionally, under the educational support system, it encourages a two-way educational collaboration between native and non-native Aboriginal Australian. Although the Aboriginal language education is not uniform across all states in Australia, it has spread to and reached at a national level.

In any case, the efforts and steps taken by the Australia to preserve and recover Aboriginal Australian languages and cultures serves as a suggestive model for other nations like Japan.

(from left) Associate Professor Zane Ma Rhea, Professor Maeda and Senior Lecturer Peter Anderson, whose root lies in native Aboriginal Australian. Photo was taken in 2016 when Professor Maeda was at Monash University.